HIV/AIDS Vaccine Development: Are We Any Closer?

By Clifford Mintz, Ph.D., contributing editor

This year marks the 31st anniversary of the discovery of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the causative agent of HIV/ AIDS. At present, there are approximately 34 million people worldwide living with HIV/AIDS with more than 2.5 million new cases reported each year.

This year marks the 31st anniversary of the discovery of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the causative agent of HIV/ AIDS. At present, there are approximately 34 million people worldwide living with HIV/AIDS with more than 2.5 million new cases reported each year.

Advances in HIV prevention and antiretroviral therapies have made successfully living with HIV/AIDS a reality, and some of the newer treatments can dramatically extend the life expectancies of HIV/AIDS infected persons. Although HIV/AIDS is now a “manageable disease,” public health officials and HIV/AIDS researchers agree that a prophylactic or therapeutic vaccine represents the best option to prevent the worldwide spread of the virus and reduce the enormous healthcare costs associated with treating the disease.

Yet, despite billions of dollars in research spending and more than 20 years of laboratory experimentation, development of an HIV/ AIDS vaccine has been elusive and marked with highly publicized failures. In fact, several years ago this prompted Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Health (NIH) and a leading HIV/AIDS researcher, to announce at an international HIV/AIDS meeting that he “wasn’t sure conceptually whether we could actually have an HIV/AIDS vaccine.” More recently, however, at the AIDS 2012 Vaccine Conference held in September in Boston, he said (based on a more thorough analysis of the results from a 2009 HIV/AIDS vaccine Phase 3 clinical trial), “We proved the concept that we can do it; now we need to do much better to create a vaccine.”

A Glimmer of Hope

From 2003 to 2007, four experimental AIDS subunit vaccines were tested in more than 11,000 clinical trial participants but failed to provide any protection against HIV infection. However, as mentioned above, careful analysis of results from a 2009 Thai Phase 3 clinical trial of over 16,000 participants revealed that 31.2% of participants were protected against HIV infection. While these results suggested only modest protective (nowhere near the 80% or better protective efficacy typically required for commercialization of infectious disease vaccines), it convinced many researchers that an HIV/ AIDS vaccine may ultimately be possible and that co-immunization of a live viral vector plus a subunit and/or DNA vaccine would be required to develop an effective vaccine to protect against HIV infection.

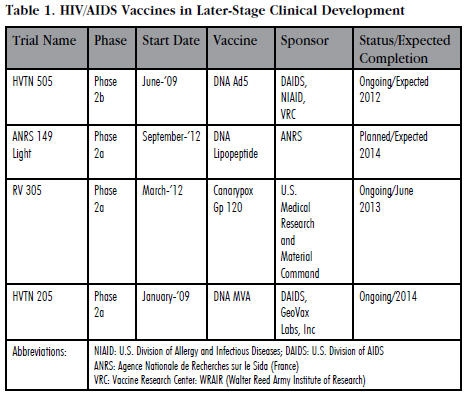

This reinvigorated HIV/AIDS vaccine researchers and helped to advance several new experimental vaccine candidates (see Table 1) in Phase 2 clinical development. Currently, there are three experimental vaccines in Phase 2a clinical testing and only one that has advanced to Phase 2b trials (see Table 1). More importantly, there are 41 other experimental vaccines currently in Phase 1 testing. Curiously, unlike most other infectious diseases vaccines which are usually developed by life sciences companies, clinical development of HIV/AIDS vaccines is mainly funded by government agencies like the NIH, philanthropic organizations, and a variety of academic institutions around the world.

Of the four vaccines in Phase 2 clinical testing, only one of them — DNA MVA — was developed and is being tested by a commercial entity. DNA MVA was developed by GeoVax Laboratories, Inc., a small 11-yearold Georgia-based biotechnology company. NIH is sponsoring the GeoVax clinical trial. The remainder of the trials is being exclusively funded by various U.S. government agencies including the NIH and the Army.

Who Should Pay for an HIV/AIDS Vaccine?

In 2011, roughly $841 million was spent on HIV/AIDS vaccine development with $615 million provided by the U.S. government, $103 million from philanthropic organizations, and the remainder contributed by European and other governments ($94 million) and the life sciences industry ($30 million). It is obvious that development of a vaccine is disproportionately being funded by the U.S. government and philanthropic organizations without much involvement from the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. Interestingly, many life sciences companies withdrew support for HIV/AIDS development vaccine programs after disappointing clinical trial results in the mid-2000s.

Bob McNally, CEO of GeoVax, feels that a lack of meaningful corporate financial and commercial involvement with HIV/AIDS vaccines has seriously impeded development. McNally said, “The U.S. government, especially the NIH, has been extremely supportive both scientifically and financially.” However, he added, “While the U.S. government generously sponsors vaccine research and helps to underwrite much of clinical trial costs, it does not pay for commercial vaccine manufacturing, nor does it pay overhead and operating costs for smaller companies seeking to develop a safe and effective commercially viable HIV/AIDS vaccine.”

Is An HIV/AIDS Vaccine Even Possible?

The quest to develop an HIV/AIDS vaccine is one of the costliest and most labor-intensive vaccine development projects in history. This has left many scientists and public policy officials to wonder whether or not development of a prophylactic or therapeutic HIV/AIDS vaccine is scientifically feasible. And that, perhaps, a better use of the government and philanthropic funds annually spent on HIV/AIDS vaccine development ought to be used to improve global HIV/AIDS education and prevention.

Nevertheless, Vincent Racaniello, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University Medical Center and former editor of the Journal of Virology, is upbeat about the possible development of a vaccine. He said, “The recent identification of human antibodies that can neutralize the infectivity of nearly every known HIV strain is a huge breakthrough.” Further, Racaniello added, “The ability of HIV to evade immune responses has always been a thorn in the vaccine strategy, and having such antibodies seemingly overcomes that problem. If we can figure out what kind of immunogen to use to elicit these antibodies, I believe that will constitute an effective vaccine candidate.”

Steve Bende, formerly of NIAID’s Division of AIDS vaccine program and once executive secretary of the NIH AIDS Vaccine Research Committee (now called the AIDS Vaccine Research Subcommittee) and now a biotechnology and vaccine consultant, also believes that development of a vaccine is a worthwhile effort. He said, “While results from the RV144 trial suggest that it is possible to develop an HIV/AIDS vaccine worthy of licensure, the best scenario has industry participating fully with government and philanthropic efforts. The emerging science hopefully can bolster, and continue to bolster, the business case for the pursuit of an AIDS vaccine by industry.”

Likewise, GeoVax’s McNally understands that future clinical development and commercialization of a vaccine will be difficult without participation of larger vaccine production companies. He said, “It has taken us 11 years to get to this point, and we are almost there. Companies like GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Pasteur, Merck, and Novartis, which have their own vaccine development programs, are always looking to smaller companies like ours that can help to develop a potential commercializable vaccine.” McNally added, “Hopefully we can find the necessary financial resources to get to that point so that we can pique their interest!”

The Science Is Still Years Away

A conceptual framework for development of a safe and effective HIV/AIDS vaccine is now in place. Nevertheless, NIH’s Fauci is quick to point out that there is no definite timeline for development of such a vaccine. At the 2012 AIDS Conference, he offered, “This [a vaccine] is not going to happen tomorrow; the science is going to take years. And even when the science gives you a concept and product, the actual design and implementation of clinical trials is going to take years.” Further, Fauci opined that perhaps the best way forward was to continue to nonvaccine modalities such as microbiocides, condoms, and education to reduce HIV infection rates and then combine those efforts with a vaccine when it becomes available. Finally, he said, “The likelihood of a vaccine has radically changed the possibility of us controlling the HIV/AIDS pandemic and eventually eradicating the disease.”