The Players In The Biosimilar Market: 6 Archetypes

By Michael Turner and Magnus Franzen

In the article “Biosimilars: What’s Happened So Far” it was outlined how biosimilars had got off to a rough start, identifying three main challenges:

- The development of biosimilars is increasingly complex and costly.

- The regulatory hurdle (especially in the us) has been tougher than expected.

- Commercializing a biosimilar is difficult and complex.

This piece builds on that background and provides details of the different players that exist in the complex biosimilar market, all of which have different characteristics, histories, reasons for entry, internal capabilities and resources available to support their programs.

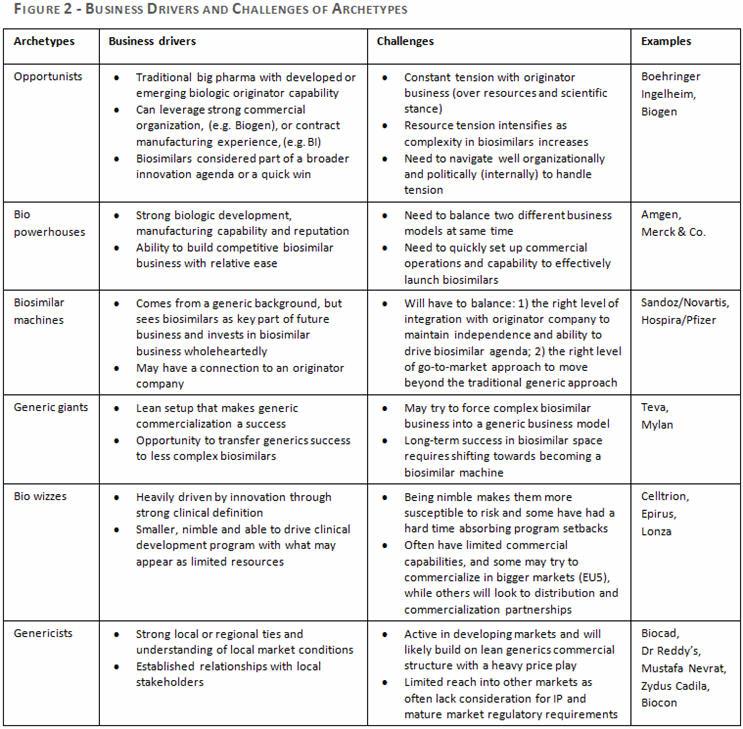

Ultimately, each player’s ability to address the challenges identified will be influenced by a number of chararacteristics including their development capability, commercial capability, reputation and business drivers for developing into biosimilars. Applying these characteristic, there are six archetypes that exist in the biosimilar market: Opportunists, Bio powerhouses, Biosimilar machines, Generic giants, Bio wizzes and Genericists. Below are definitions of each of the archetypes; the paths they are likely to follow and the strategies they will employ to commercialize biosimilars

The Six Archetypes Of Biosimilar Players

These archetypes are defined by the companies’ development and commercial capabilities and their reputation in the market. The six archetypes are Opportunists, Bio powerhouses, Biosimilar machines, Generic giants, Bio wizzes and Genericists (Figure 1).

As the market continues to evolve, this framework of archetypes helps us to understand and anticipate the likely paths that companies will follow in their pursuit of biosimilar success. It may also help companies with products facing biosimilar competition in the near future to better prepare a more targeted strategy that takes into consideration the strengths and weaknesses of their competitors. Figure 2 sets out the main business drivers and challenges for each archetype.

An Opportunist: Boehringer Ingelheim

Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) saw an opportunity and built the case for going into biosimilars in two ways. First, BI was expanding its biologics capability and trying to build a stronger oncology business (first oncology asset launched in 2013). A large part of the effort required to understand mechanisms and biologic molecules offered synergies with biosimilar development. The view was that biosimilar development could help strengthen the originator business and drive innovation.

Second, BI wanted to leverage extensive experience from its contract manufacturing arm, BioXcellence, as biosimilar development and manufacturing would tie well into that strength.

It seems, however, that the company underestimated the complexity of biosimilar development as well as the effect on the internal politics of the company. As the risk-reward dynamic changed, BI took a step back on its commitment to biosimilars and redirected resources back into the originator business. This can be seen in the recent termination of the development of some biosimilar programs that would not be fast enough to market and a refocusing of its overall effort in this area.

A Bio Powerhouse: Amgen

A company that embodies the spirit of the Bio powerhouse is Amgen. The company has an almost unrivaled biologic development and manufacturing capability, and its biosimilar pipeline is one of the strongest in the industry. Additionally, the reputation and legacy of the company help to position it as a biologic leader.

Amgen has also had to tackle internal tension between its originator and biosimilar businesses, since its own originator drugs will be coming under biosimilar competition in the near future. This tension is partly dealt with by taking a stance of: ‘biosimilars are so difficult to do right that only we can really do it.’

Internally, there is a clear commitment to the biosimilar business with over $1 billion being invested in the program. At the same time, Amgen has several key products – with a combined value of more than $3 billion – that are losing exclusivity and face potential biosimilar competition. Thus, the move into biosimilars may partly be a way of filling the void left by this ‘patent cliff’ by taking the position that a strong offense is the best defense.

A Biosimilar Machine: Sandoz/Novartis

Sandoz leverages its parent company Novartis’ biologic development and manufacturing capability, as well as its commercial organization. At the same time, the company is a separate business unit within the Novartis group and enjoys a certain autonomy. This autonomy may be important in handling the likely internal tension between the biosimilar and originator businesses and, as long as Novartis is able to keep that balance, Sandoz may remain a strong competitor in the biosimilar space.

Novartis has shown commitment to Sandoz’ biosimilar program and like Amgen, it has a substantial development budget for quite a broad pipeline.

Sandoz’ approach to biosimilars seems almost like that of their generics business, i.e. ‘we can copy everything.’ However, as the complexity of its development and commercialization increases with next generation molecules coming through the pipeline, Sandoz may have to focus its efforts more and play to its strengths in terms of specific therapy areas, channels, etc.

A Generic Giant: Teva

Teva currently has two biosimilars in a number of different markets and seems to be taking a lean approach to its commercialization, but it looks like its biosimilars are experiencing only limited success and uptake.

The complexity of biosimilar development makes it quite difficult to develop the capability organically within a generics company. Teva tried to overcome this difficulty by partnering with Lonza Group in 2009. Unfortunately, the partnership did not last, as the companies underestimated the complexity of bringing these products through development.

In October 2016, Teva made another attempt at growing its biosimilar business through partnership; this time with Celltrion. This partnership gives Teva commercialization rights to Celltrion’s rituximab and trastuzumab biosimilars, which are both monoclonal antibodies for oncology.

A Bio Wiz: Celltrion (And Others)

The Bio wizzes have strong clinical definition, but their size can make it harder for them to absorb the risks of development. The most telling example of this is Epirus Biopharmaceuticals, which was forced to file for bankruptcy after experiencing difficulties financing its ongoing development program without having a significant commercial success to help fund that investment.

Celltrion, a South Korean company, is one of the more successful Bio wizzes. With a fairly strong pipeline of new products and the first monoclonal antibody biosimilar (Remsima/Inflectra) in market, Celltrion has managed to play to its strengths and avoid major setbacks.

Bio wizzes do not have a strong commercial capability to help bring their biosimilar assets to market. They largely seem to follow a model of partnership with global players, and Celltrion has successfully realized this business model. The company has reached commercialization deals with several other companies for its biosimilar of Remicade (Remsima/Inflectra) and recently signed a deal with Teva for the commercialization of two of its oncology biosimilars that are coming through the pipeline.

Nonetheless, this model also has its challenges. The contracting biopharma company, Lonza, and Teva discontinued their biosimilar development joint venture in 2013. According to Lonza COO Stephan Kutzer, it was because “in our assessment those investments in biosimilars will require more capital than initially planned and will also take more time until they reach the market.”

A Genericist: Biocad

Russian biotech company, Biocad, illustrates the important role of local players in its markets of origin, as well as in other developing countries. Biocad has several biosimilars with marketing approval in Russia as well as Turkey and Brazil.

Genericists’ key strengths are local ties and relationships, so it is not surprising that they often partner with local players when bringing their business to other countries. For example, Biocad partnered with the local company, Koçak Farma, in the commercialization of its biosimilar portfolio in Turkey. Similarly, the Indian company, Zydus Cadila, partnered with Eczacibasi Ilac Pazarlama, to enter Turkey.

We See Clearer Future Paths Emerging

The biosimilar market is highly dynamic and, as a new generation of monoclonal antibody biosimilars come through the pipeline, the paths to success in this space are starting to become clearer. Determining which path is the right one will likely depend on the company archetype, as well as the level of competition and the specific market dynamic of where they will be playing.

At the macro level, the complexity of biosimilar development will likely continue to be a determining factor for many companies. As it stands, this seems to give the Biosimilar machines and Bio powerhouses a competitive edge, and companies such as Sandoz and Amgen have strong pipelines and capability to make the most of them. However, this will depend on how well they manage the differences and/or tension between their biosimilar and originator businesses.

Opportunists will face a similar challenge, and may have to gravitate towards the Biosimilar machines or Bio powerhouses approach by firmly committing to their biosimilar program and building their development capability, either organically or through partnerships with Bio wizzes.

Similarly, the success of the Generic giants may depend on their ability to grow their development capability. They will most likely do this through partnerships with companies with a stronger bio-clinical program, but they can bring resources to put behind the development program and commercial capability to these partnerships. In the process, they may have to adapt their business model to the needs of the biosimilars, as it will differ from that of generics, especially in the use of more medical and access-focused customer-facing roles.

The Bio wizzes may welcome an environment of increased partnership as they are often in need of resources to ‘survive’ until the end of Phase 3 development, as well as commercial capability or support to bring the products to market.

The Genericists are not likely to play a major role on a global scale, but may pose significant competition in key developing markets, such as India, China, Turkey, Russia and Brazil.

In summary, as the stakes get higher with more complex molecules coming through the pipelines, the six archetypes of companies will need to find different paths to success. A company’s development capability, commercial capability, and reputation, in conjunction with the specific market context, will define what approach will most likely help it achieve success in this highly competitive and dynamic environment.

Authors:

Michael Turner is a life sciences expert at PA Consulting Group, with over 17 years of commercial strategy experience. Michael partners with clients to address strategic product and portfolio challenges and implement strategies to maximize asset value.

Magnus Franzen is a life sciences expert at PA Consulting Group. With a background in strategic and market research, Magnus leverages a deep knowledge of the dynamics of commercializing pharmaceuticals in a changing healthcare environment to support clients in key strategic areas, such as customer engagement, multichannel marketing and value beyond the pill.

Magnus Franzen is a life sciences expert at PA Consulting Group. With a background in strategic and market research, Magnus leverages a deep knowledge of the dynamics of commercializing pharmaceuticals in a changing healthcare environment to support clients in key strategic areas, such as customer engagement, multichannel marketing and value beyond the pill.