What Makes Roche's Approach To Partnering Unusual

By Rob Wright, Chief Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @RfwrightLSL

Listening to Sophie Kornowski-Bonnet, Ph.D., talk about Roche’s approach to partnering is overwhelming. In her distinct French accent, she recounts anecdote after anecdote of a 30-year pharma career that spans not only multiple companies but multiple continents.

It’s no wonder she landed at Roche, a company rich with successful and long-running partnerships with companies such as Chugai Pharmaceutical. That commitment to partnering is even more evident when you notice that Kornowski-Bonnet, the company’s head of partnering, also serves on the senior leadership team — a rarity among top biopharma companies. That’s not the only fact, though, that could be considered unusual when talking about Roche’s approach to partnering.

A FOCUS ON INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY

According to Kornowski-Bonnet, there are three ways companies typically approach partnering. “Some companies have a completely independent partnering group tasked with finding and evaluating innovation,” she explains. “They invest almost independently, and if they like it, the innovation is brought back into the company to be integrated into the pipeline.” Another model involves the partnering team reporting to either R&D or commercial. The partnering team at these companies is basically trying to fulfill a request, such as finding a drug for a specific disease. Roche takes more of a hybrid approach.

“The Roche Partnering organization was established to collaborate and coordinate in full alignment with pRED [pharma research and early development], but still be independent and autonomous,” she explains. “If your partnering organization is embedded within R&D, you might end up thinking or feeling in ways similar to them, which doesn’t allow for the proper distance required to make big, bold decisions.”

The concepts of independence and autonomy permeate any discussion regarding Roche’s partnering organization. That seat Kornowski-Bonnet holds on Roche’s executive committee also makes her directly report to the CEO. That’s a different structure from what is in place for her Genentech Partnering counterpart. It is different still at Chugai Pharmaceutical. Back in 2001, Roche acquired a majority stake in the Japanese company, but for the most part, Chugai still operates independently. “We license and develop Chugai products for patients around the world. If we have something from outside of Japan that we think could be attractive to Chugai and the Japanese market, then my team would be ready to support.” In other words, though she sits on Chugai’s board, how the company approaches partnering is fairly independent of the overall Roche organization.

She admits the different structures established for Roche’s various partnering organizations can be demanding. “It shows you just how challenging my mission can be. I’m looking for early-stage innovation for pRED (pharma), innovation for the Roche group (business operations), coordinating with gRED (Genentech research and early development organization) so we aren’t duplicating efforts, and working with Chugai on numerous projects we established during our partnership.”

THE CHALLENGES OF MANAGING A GLOBAL PARTNERING ORGANIZATION

As an organization, Roche Partnering consists of about 90 people geographically dispersed around the world and organized under the following six disciplines:

- Immunology, Infectious Diseases, and Specialty Care

- Neuroscience, Ophthalmology, and Rare Diseases

- Oncology and Cancer Immunotherapy

- Collaborations with Academia

- Innovative Technologies

- Personalized Healthcare

“The team is scientifically focused and commercially seasoned, so they are able to evaluate innovation in a deep way,” says Kornowski-Bonnet.

Having this kind of a diverse and globally dispersed organization creates its own set of opportunities, as well as challenges. For example, just getting the whole team together — physically — is so difficult that Kornowski- Bonnet says it happens only once a year. That challenge, though, breeds opportunity. “We don’t look to these meetings as a way of simply reviewing how we are doing as a partnering organization,” she explains. “We dig into topics that are helpful to the team.” For example, at this year’s gathering they explored the concept of agility and how to grow and improve at it. There’s also time spent on team building. “Oftentimes, we are very transactional and busy in our work, which involves a lot of travel,” she explains. “So we try to slow down a bit during these off-site meetings to improve how we engage with one another as a team.”

The Roche Partnering group also gets together with Genentech Partnering (the organization that does deals on behalf of gRED) every other year to align on best practices. This is a smaller group involving senior leaders of the two partnering organizations. Senior leaders of Roche Partnering also meet Chugai’s partnering team on an as-needed basis.

THE ROOT OF EXTERNAL PARTNER

The Roche group currently has 222 active external partnerships. When asked for an example of one that has been working well, Kornowski-Bonnet is quick to reference Chugai. “Initially, Chugai was an agreement to share each other’s pipelines and, whenever interested, to opt in on each other’s research,” she notes. “But as the relationship has grown, we’ve been able to share tremendous knowledge while keeping our research organizations independent.”

The Roche group currently has 222 active external partnerships. When asked for an example of one that has been working well, Kornowski-Bonnet is quick to reference Chugai. “Initially, Chugai was an agreement to share each other’s pipelines and, whenever interested, to opt in on each other’s research,” she notes. “But as the relationship has grown, we’ve been able to share tremendous knowledge while keeping our research organizations independent.”

The partnership with Chugai had an unusual beginning; the former Roche CEO and Chugai’s CEO had a personal relationship, and they started talking on how best to collaborate. Kornowski-Bonnet says that for her team, partnerships typically begin with the identification of a product or science. “Genentech is a good example. Initially, we were focused on the medicines they were discovering and developing, but over time we became more interested in their full pipeline.” And like Chugai, despite the affiliation with Roche, Genentech keeps its research independent, too.

4 KEYS TO PARTNERING SUCCESS

Kornowski-Bonnet shares that 45 percent of Roche’s current R&D pipeline has been externally sourced. Further, 36.5 percent of total pharma sales are currently generated from partnered products. Such a large partnering impact means they must begin with a large amount of potentials. “We typically screen about 2,500 projects every year,” she says. Some of these opportunities are brought to Roche unsolicited, while others are actively sought out by the partnering team. For example, the Roche Partnering team reviews abstracts of conference programs of therapeutic interest looking for opportunities. “Being organized by therapeutic area helps us to always be in scouting mode, and we only progress on something if it makes sense,” she attests.

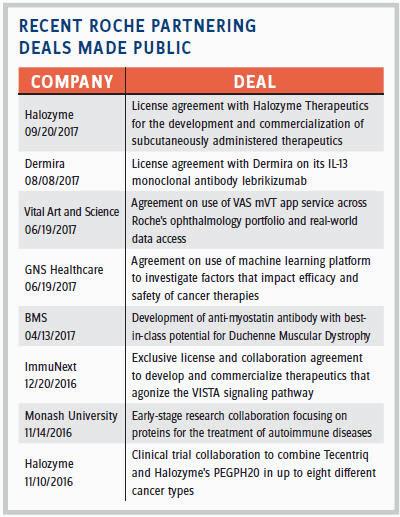

So how often do those potential partnerships “make sense”? Of the 2,500 projects screened throughout the year, she estimates that only about 100 end up having a confidentiality agreement (CDA). In 2016, Roche Partnering closed 44 partnering deals. (For a sampling of those made public, see table at right). Some of the deals Kornowski-Bonnet references by name include GNS Healthcare, a company focused on precision medicine. Roche hopes to leverage GNS’ reverse engineering and forward simulation (REFS) platform to power the development of novel cancer therapies. Some other high-potential deals she mentions include Foundation Medicine, a company using genetics to help select drugs for cancer patients; InterMune, a biotech focused on pulmonology and fibrotic disease therapies and acquired by Roche in 2014; Flatiron Health, a healthcare technology and services company; and SQZ Biotech, a privately held company developing cellular therapies.

According to Kornowski-Bonnet, almost all successful partnerships begin with scientific alignment. “We should be passionate about the same things, or we are bound to disagree at some point.” To gain alignment there are key questions to consider, and those vary depending on the therapeutic area. She gives the following example:

- Can a next-generation antibody platform enable a broader target space?

- How excited are we about it?

- Which indications can be unlocked by those new targets?

Kornowski-Bonnet believes there are four keys to partnering success. First, there has to be a common interest in the science. Second, there has to be an honest relationship based on transparent information and knowledge sharing. Third, there needs to be an appetite for collaboration and a willingness to work together and learn from each other. “This is really important because if someone knows it all, has done it all, and can do it all, they are not going to be a productive partner — for anybody.” Finally, members of the partnership need to have a problem-solving mindset. “When you have a problem — and you will have problems — you need to decide if it’s important, why the problem happened, and how to collaborate on finding solutions that are the best for both.” She says usually you can tell from the first meeting which of those keys to success are present and which are going to be lacking.

WHEN PARTNERSHIPS DON’T GO AS PLANNED

Kornowski-Bonnet explains the partnering process is similar to a scientist in a lab who wants to gather enough information to determine if a potential drug should be “killed” early so as to not waste time and resources. Usually when a partnership doesn’t work out, she says, it’s due to the science. “That’s OK, though; it’s all part of R&D.”

But every now and then, she admits the company has to discontinue a relationship because it isn’t worth trying any harder. “We could go back and redesign a study, but sometimes you just need to know when to say enough.” Not being able to trust a partner is another reason for failed collaborations. If it’s too challenging to interact due to misaligned expectations or a lack of transparent information sharing, then a partnership is usually ended quickly.

“When I hit a roadblock in a partnership, I take the time to reflect and use it as a learning opportunity to improve how I approach the next partnership. I value the projects we terminate just as much as the ones we pursue. This helps you to not only know the difference between the two, but improve upon the deals you will do later.”

It’s a risk pursuing any partnering deal, especially in terms of time and manpower. For those deals that look really interesting, between 20 and 100 people may be involved to just complete the due diligence step. At Roche, some of the people involved in that process are the members of pRED who help determine if the innovation is something to integrate into Roche’s portfolio. But Kornowski-Bonnet stresses that there is more to it than ticking off boxes when it comes to Roche’s approach to partnering. “A deal is a story between people. I reinforce with my team that they need to pay attention to the ‘electricity’ that takes place between people and the flow of engagement between parties, as all of that is nearly as important as the quality of the data and the science. Because when you sign an agreement, you will be wedded for a long time with people — who are now your partners.”