Champions Against Nonsense – A Better Way To Talk (And Think) About Quality

This is the second of three articles focusing on an effort to address what appear to be systemic issues across quality departments, informed by a multinational group comprising chief quality officers (CQOs) from pharma, device, animal health, and consumer goods companies. The first part focused on how quality departments are often perceived negatively in the company, the lack of a common definition of quality, and the 10 things quality departments should stop doing. This part addresses how to reframe the way we view and discuss quality, how to better engage stakeholders, and an alternate view of how quality can add value to the company.

At the annual FDAnews Inspections Summit in late October 2018 in Bethesda, MD, Xavier Health director and former head of quality for Merck’s North Carolina facility Marla Phillips shared her research on why pharma quality units are failing to meet their challenge and how they could be redesigned to add more value to the company, in a presentation titled “Why Quality Doesn’t Matter.” Phillips has chaired a series of pharmaceutical and medical device conferences cosponsored by the FDA for more than 10 years and has participated in and co-led a number of agency-sponsored initiatives.

Stop Using Fear Tactics

Much of the time, quality professionals use fear tactics to influence, measure the means detached from the end, and don’t understand the business, Phillips said. For example, if asked why something must be done, she characterized the answer, “because we will get an FDA enforcement action if we don’t,” as “weak,” noting “there is always FDA enforcement looming.”

She suggested learning how to communicate in terms of business terminology instead of basing it on possible inspection or enforcement results. To do that, quality professionals need to learn more about other aspects of the business. “If you actually involve yourself in the business and understand it more deeply, then you are going to be a better partner for your cross-functional peers.”

Phillips provided three examples of ways quality could communicate differently with its business partners if it became better grounded in the overall business, with no mention of FDA regulations or enforcement:

1. How would you communicate the need to your cross-functional peer to close investigations within 30 days?

“I am working to identify how to increase the percentage of time your equipment is operational. Studies have shown that if failures are investigated within 30 days, then there is a greater chance the true root cause can be identified due to the freshness of the incident in the minds of the employees. What can we do together to decrease the amount of time it takes to close investigations?”

2. How would you communicate the need to your cross-functional peer to engage more fully in the quality management review meeting?

“I think if we work together, we can identify signals to prevent failures that shut down your operations. Can we discuss the measures that are most important to you and how we can improve those measures? If we share this cross-functionally and with senior management, then we can co-own the success of this outcome. Would you mind presenting this information each month so you can share the insights you have on what is actually happening?”

3. How would you communicate the need to your senior management to increase headcount in your understaffed quality organization?

“Our total time offline increased by 13 percent for each of the past six months due to a gap in headcount in the quality organization. This gap has already cost our site $3.4 million. I can share the detailed numbers with you, but here are the options we have developed:

- Hire three full-time employees starting next month. Impact: no increase in expense, since these employees are in our budget.

- Hire five contract employees for this fiscal year to address the backlog we have. Impact: no increase in expenses, since five contract employees equal three full-time employees with benefits. However, training temporary help results in lost time.

- Continue as is. Impact will continue, but the percent of time offline will grow from 25 percent to 32 percent of our fiscal year projections since our forecast volumes increase. Total loss this FY is $9.3 million.”

Become Champions Against Nonsense

One piece of feedback the CQO team received from its cross-functional peers was to examine edicts coming down from senior quality management to see if they make business sense.

“We need to take a step back to see if what is coming down makes sense and what impact it will have on the operations instead of just bolting on modules and new requirements,” Phillips said.

“I would propose we become champions against nonsense. Step back and ask the question, ‘Does this make sense?’ You will be a huge asset no matter where you are in the organization. Be a champion against nonsense and ask the question, ‘Why?’”

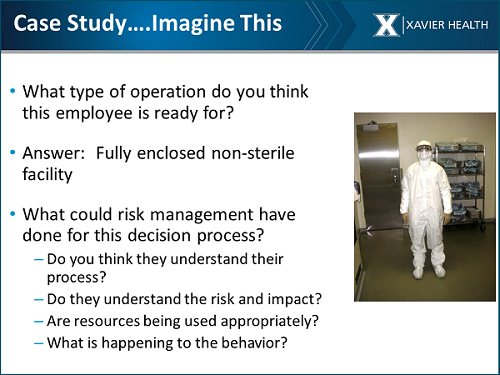

As an example, Phillips shared a pharma gowning procedure that she experienced at a major global pharma company in Puerto Rico (see below).

“This is how they had us gown, with oxygen masks, for a fully enclosed non-sterile facility,” Phillips said. “In addition, once we got out into the manufacturing area, we had to wipe off our gowns with a handy wipe. And of course, you can’t even reach your back. It was so crazy.”

“So, quality was not going out on the floor, because who would want to get dressed like that? Everyone knew it was ridiculous. Your brains are already shutting off. We need to be champions against nonsense.”

Engage Stakeholders To Be Successful

Phillips asked, how do you create quality for the 21st century? “It has to be grounded in ‘why.’ We communicate the ‘why’ based on understanding our stakeholders.”

To illustrate the importance of knowing why, Phillips played two short videos. One was by author, motivational speaker, and organizational consultant Simon Sinek, who spoke about leadership, noting that, “we follow those who lead, not because we have to, but because we want to. We follow those who lead, not for them, but for ourselves. And it’s those who start with ‘why’ that have the ability to inspire those around them or find others who inspire them.” The second video by comedian Michael Jr. focused on the importance of knowing one’s purpose. He said, "When you know your ‘why,’ your ‘what’ becomes more clear and impactful."

Phillips explained that a better understanding of internal and external stakeholders, their needs, and the language they use will be fundamental to redesigning the role of quality. “We need to shift the way quality is communicating if they want to get buy-in, and also to be sure they understand this is part of the problem.”

Instead of looking at the number of open CAPAs and failures and 483s, she suggested talking about number of days off the market, number of man-hours wasted or saved, and greater net profit. “Those terms are what our stakeholders understand, including the CEO.”

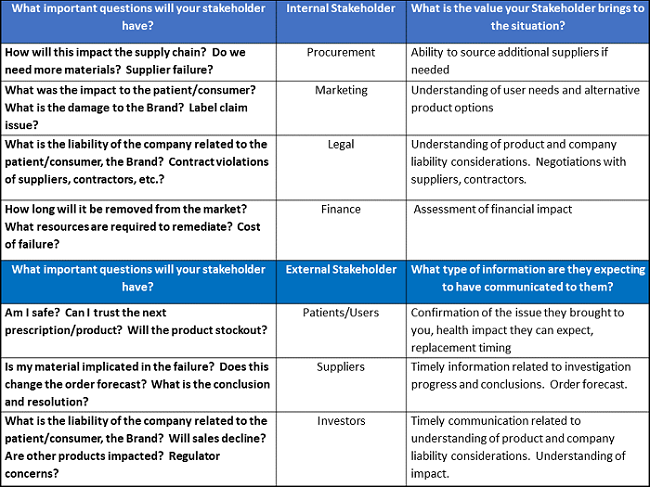

Using an example of a verified product failure complaint, Phillips suggested identifying internal stakeholders and having discussions with them to determine what questions they have and what value they will bring to the situation. For external stakeholders, also determine what questions they will have and what type of information they will expect to be communicated to them. She provided some examples (see below).

An Alternate Vision Of Quality

Characterizing the current state of quality departments in regulated industries, Phillips said they are the ones that run around and make sure others have their jobs right, work to close out deviations in 30 days, ask why training was not done and why an SOP was not reviewed, and point out grammatical errors in documents.

“It is just running and chasing,” Phillips said. “We over-check what someone else has done. That is not very conducive to human behavior. It is not good for the people we are overseeing, because they know somebody is coming behind them. And it is not good for us, because our brains are not wired for doing very detailed ‘let me be sure you did your job right’ level of effort, because it is boring.”

Phillips and her CQO team have discussed among themselves and with cross-functional peers ways in which quality could add more value to the company. These include a better understanding of risk to the business of new initiatives, focusing on right-first-time rather than compliance, removing barriers, and understanding the value they bring to investigations and operations.

Phillips said that quality can become one of the greatest assets to the CEO of a company by understanding risk, intended use, and the needs of internal and external stakeholders. “Risk is a term that quality is very used to talking about, but I am talking about risks beyond quality. What are all the risks associated with whatever you are trying to push through as a new initiative? What are the benefits and risks of doing something or not doing it?”

If instead of focusing on compliance, the quality group is asked to improve the right-first-time rate in everything it does, then compliance becomes a natural outcome, and cross-functional partners become co-owners, she maintained.

Quality can also become an asset by removing barriers instead of proposing new initiatives. “In order to remove barriers, you have to understand the business,” Phillips said. “In most cases you will be looking at streamlining and efficiencies and ways to do things to increase the ability of your cross-functional peers to do the right things the first time.”

Phillips asked, “What if quality is an organization that mobilizes enterprisewide quality effectiveness and optimizes patient safety and business success? The way we are going to do that is through innovative systems and critical thinking, grounded in science, data, stakeholder awareness, and regulatory intelligence. It is similar to an operations excellence group from a systems standpoint. But we are going to be bringing in innovative systems that may even include artificial intelligence (AI) for continuous product quality assurance, for example.”

Quality could also facilitate the ability of shop floor personnel to know in real time that their output is not similar to what it has been. Maybe it looks similar, but there is either a drift or step jump, and they can see it right then and there. “So, we have systems that put data at their fingertips in real time, then they can stop the process. Their manager actually owns that investigation.”

The value quality brings to failure investigations is the systems knowledge of what has been happening historically, what is out on the market, what change controls are in place, and what is in the validation documents. “Why would quality own that instead of the manufacturing manager or supervisor out on the floor, to allow them to better understand what is going on with the product and process?” Phillips asked. “When quality closes investigations, there are repeat failures. That is because it is not being driven by the right people who are owning the systems.”

“We cannot just say, ‘OK operations, you own that now.’ We have to take a look at the whole infrastructure to support them owning it. That includes having it in their objectives, linked to their performance appraisal, and supported by the metrics that are driving the right information and the systems they need to make the decisions and involve the critical thinking that is needed.”

The third and final article in the series will further examine how to achieve cross-functional ownership of quality and the efforts of the CQO team to build quality for the 21st century. Portions of the CQO team will convene for discussion, input, and networking at the FDA/Xavier PharmaLink pharma conference in March 2019 and at the FDA/Xavier MedCon medical device conference in April/May 2019.

About The Author:

Jerry Chapman is a GMP consultant with nearly 40 years of experience in the pharmaceutical industry. His experience includes numerous positions in development, manufacturing, and quality at the plant, site, and corporate levels. He designed and implemented a comprehensive “GMP Intelligence” process at Eli Lilly and again as a consultant at a top-five animal health firm. Chapman served as senior editor at International Pharmaceutical Quality for six years and now consults on GMP intelligence and quality knowledge management and is a freelance writer. You can contact him via email, visit his website, or connect with him on LinkedIn.

Jerry Chapman is a GMP consultant with nearly 40 years of experience in the pharmaceutical industry. His experience includes numerous positions in development, manufacturing, and quality at the plant, site, and corporate levels. He designed and implemented a comprehensive “GMP Intelligence” process at Eli Lilly and again as a consultant at a top-five animal health firm. Chapman served as senior editor at International Pharmaceutical Quality for six years and now consults on GMP intelligence and quality knowledge management and is a freelance writer. You can contact him via email, visit his website, or connect with him on LinkedIn.