Looming Cadillac Tax And ACOs Distort Healthcare System

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

By the time this article goes to press, the Supreme Court may have ruled on the constitutionality of subsidies for health insurance flowing through the federal exchange. But other distortions caused by Obamacare are rippling through the healthcare system. Two clear examples are the looming “Cadillac Tax” on generous health plans and unfolding theatrics regarding accountable care organizations (ACOs).

By the time this article goes to press, the Supreme Court may have ruled on the constitutionality of subsidies for health insurance flowing through the federal exchange. But other distortions caused by Obamacare are rippling through the healthcare system. Two clear examples are the looming “Cadillac Tax” on generous health plans and unfolding theatrics regarding accountable care organizations (ACOs).

CADILLAC TAX TO HIT 60 PERCENT OF EMPLOYER PLANS

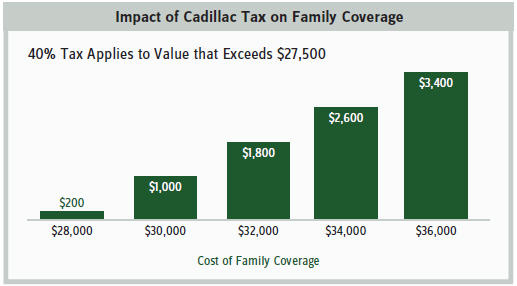

The so-called “Cadillac Tax”— the 40 percent excise tax on the value of health plans that exceed a threshold the architects of Obamacare find too munificent — is the latest case in point. The tax is collected on plans whose value exceed $10,200 for individual coverage or $27,500 for family coverage. As Professor Gruber, a key architect of Obamacare, gleefully explained in a famously leaked video, Democrats deliberately “mislabeled the provision as a tax on insurance plans when we all know it’s a tax on people who hold those insurance plans.”

Although it does not go into effect until 2018, many employers and unions are already adjusting their plan offerings in anticipation of the hefty fee impacting their multiyear contracts with employees. Business and labor are unified in seeking its repeal, and bipartisan legislation has been introduced to rescind the tax.

“Cadillac Tax is really a misnomer; potentially any employer can be hit by the tax,” said Beth Umland of Mercer, a major health benefits consulting firm. Mercer predicts that by 2022 more than 60 percent of plans will be ensnared by the pernicious tax, up from just 22 percent initially.

Part of the problem is that employee contributions to their own healthcare through health savings accounts and flexible spending accounts are counted toward the threshold that triggers the excise tax. Why should employee healthcare savings vehicles be conflated when employers purchase health insurance that’s considered too generous? The pretax employee-funded accounts have served as an important bulwark as employers have shifted more costs to employees.

The second major reason nearly two-thirds of employers will eventually be taxed for offering coverage deemed “too generous” is that the threshold is indexed to the consumer price index plus one percent, which lags behind health inflation. The CPI grew at 2 percent last year, while the Congressional Budget Office projects health inflation to rise at 5.6 percent over the decade. It should be no surprise that the 40 percent tax will raise $87 billion over the next decade and grow in importance, likely forcing employers into skimpier health plans with substantial deductibles and costsharing and narrow provider networks akin to the offerings in the Obamacare exchanges.

This paternalistic view that government knows best how much healthcare an individual should be provided by willing employers is reflected in the typical deductible for a family plan in the “silver” or middle-tier plan offered in the Obamacare exchanges: $6,000 in 2015 (and slated to rise by double digits next year). While the administration touts evidence of the number of uninsured falling in recent years, most newly-insured have policies with such substantial cost sharing and narrow networks of providers they’re deterred from seeking routine care. A looming tax that is likely to result in many employers substantially hiking deductibles or scrapping pretax health account vehicles that assist these individuals with their out-of-pocket expenses will only exacerbate the problem.

ADMINISTRATION SUPPORT OF ACOs REGARDLESS OF RESULTS

Meanwhile, the administration is undertaking bizarre contortions to maintain interest in another key feature of Obamacare: Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) ACOs — provider groups tasked with coordinating care and reducing healthcare costs. ACOs were envisioned to encourage megahospital systems to emulate integrated health organizations such as the Mayo Clinic and Geisinger Health System to create shared savings for the Medicare program. But in a series of actions, the administration abandoned almost any pretense that such organizations will actually accept risk and contain costs.

When the program was first announced in 2011, CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) called for MSSP (Medicare Shared Savings Program) ACOs to accept two-sided risk: ACOs that contain costs below benchmark spending could share in the savings, but those whose costs exceed the benchmark must accept part of the loss, just like any capitated insurance plan, except that the government would also share in the losses.

But, following stakeholder backlash and over 1,300 submitted comments, CMS caved in the final rule. Participants were provided with the option to partake in a two-sided risk model or enjoy a three-year period of risk-free participation after which ACOs would be required to share in both the savings and the risk. Just five out of 405 ACOs volunteered to participate in two-sided risk. Five! The other 400 got to play a game of “Heads, I win. Tails, you lose.” In this case, “you” is the taxpayer holding the bill for providers who fail to hit their spending targets.

With the three-year window of one-sided risk about to expire, the ACOs (i.e., mostly large hospital systems) mounted a lobbying campaign to protect their risk-free scheme. In November 2014, the National Association of ACOs commissioned a survey that claimed nearly two-thirds of member ACOs would leave the program unless substantial “improvements” were made. Several weeks ago, CMS issued a rule to allow ACOs to continue with their risk-free participation for another three years. Sensing a pattern here?

In its announcement of the retreat, CMS crowed, “We are encouraged by the popularity of the Shared Savings Program, particularly the popularity of the one-sided model.” How about expressing disappointment for failure to implement a program that actually saves money?

Only one-fourth of the 220 ACOs whose contracts are set to expire at the end of this year produced any shared savings, and many of the others are expected to drop out of the program. A Medicare Payment Advisory Commission analysis last fall found that ACOs had saved a whopping 0.3 percent! Jiminy. MedPAC and the health policy community have been very supportive of the ACOs, so one can only imagine the tortured computations and analysis required to show even the slightest savings.

Nonetheless, the administration has put the word out that these large health systems must be nurtured and protected over competing delivery systems, such as independent physician practices that already provide integrated care and large savings, shockingly, to patients AND the system, as they are paid far less for providing the identical services. Presumably, fewer providers mean fewer entities to control or influence. Big government likes big bureaucratic providers.

This is particularly confounding given the evidence that hospital employment of physicians results in less efficiency and higher costs. A recent Journal of American Medical Association study of 4.5 million patients in California found: 1) expenditures per patient were 10.3 percent higher for physician groups owned by hospitals than independent practices; and 2) expenditures were 19.8 percent higher for physician groups owned by multihospital systems.

Yet the threat of being boxed out of a delivery model that has led to vertical provider consolidation is resulting in troubling employment decisions by physicians. A recent study by Merrit Hawkins found a substantial shift toward hospital-employed physicians, with 90 percent at hospitals versus just 10 percent in independent practices. The administration’s unwavering support for ACOs, despite their performance and its lack of anti-trust enforcement in the health provider sector where megahospitals control entire communities’ healthcare, has fueled consolidation of healthcare providers.

At what point can the administration take note of empirical evidence of the result of their policies rather than hew to the ideological dogma that provided the basis for policy decisions made years ago? They won’t. As Gruber points out, their game plan has been and will continue to be: Keep the charade going as long as possible, dig the hole ever deeper, and at a certain point it will be too big to dig out.