Negotiation of Medicare Drug Prices

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

Already anxious about the intense scrutiny of aggressive pricing strategies by several companies, the pharmaceutical industry went into DEFCON 1 when Republican presidential frontrunner Donald Trump expressed his interest in negotiating drug prices for Medicare.

Already anxious about the intense scrutiny of aggressive pricing strategies by several companies, the pharmaceutical industry went into DEFCON 1 when Republican presidential frontrunner Donald Trump expressed his interest in negotiating drug prices for Medicare.

Who could blame the populist, bestselling author of The Art of the Deal, who had also asserted that he would negotiate much tougher trade deals with China, Japan and Mexico, for claiming that he could get pricing down on prescription drugs? After all, Trump seems untethered to Republican and conservative free-market dogma when it comes to healthcare and a number of other economic matters.

But his actual claim was quite curious. At a rally in New Hampshire he said, “These guys that run for office, that are on my left and right and plenty of others, they’re all taken care of by the drug companies. And they’re never going to put out competitive bidding. So I said to myself, wow, let me do some numbers. If we competitively bid drugs in the United States we can save as much as $300 billion a year.”

Really? That’s a lot of money, particularly when National Health Expenditures data shows all of American spending on prescription drugs — which includes all government programs, all commercial plans and all out-of-pocket of every individual in the country – totaled just $305 billion in 2014 (the most recent year data was available)! Medicare’s portion of that spending was $143 billion.

So, “The Donald” is prone to hyperbole Shocker! But what about his underlying contention that the Medicare program could benefit from competitive bidding?

Mr. Trump should be heartened to learn that competitive bidding is precisely how the Medicare drug program has operated since its inception about 10 years ago. Medicare contracts with numerous private health plans that, in turn, negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical manufacturers and pharmacies. The more effective the drug plan is at keeping down costs, the lower its premium will be to attract beneficiaries. Beneficiaries are attracted to the most efficient plans, and enrolling in those plans restrains Medicare expenditures.

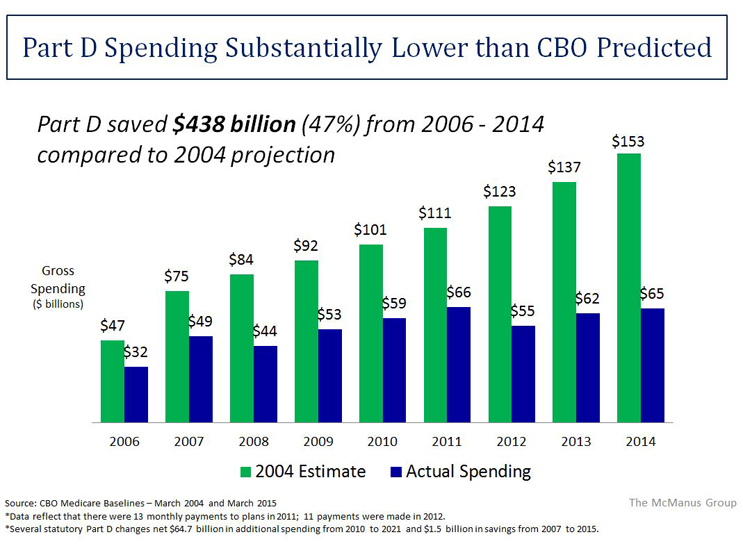

That competitive bidding design has worked better than anyone dreamed. The Medicare Part D drug benefit is a rare government success story. Actual costs have come in about 45 percent below initial projections, and patient satisfaction is consistently sky high.

Notwithstanding the impressive results, for more than a decade liberals and the Democratic establishment have tried to empower the Secretary of Health and Human Services to directly negotiate prices with pharmaceutical manufacturers. They have urged repeal of the so-called “non-interference” clause in the statute which prohibits the Secretary from interfering in the negotiations between the plans and pharmacies.

§1860-D(11)(i) of the Social Security Act: “In order to promote competition under this part and in carrying out this part, the Secretary –

- May not interfere with the negotiations between drug manufacturers and pharmacies and prescription drug plan sponsors; and

- May not require a particular formulary or institute a price structure for reimbursement of a covered Part D drug.”

The theory is that the Secretary would have more leverage negotiating drugs on behalf of all 37 million beneficiaries than the competitive, pluralistic market has achieved. But that contention fails to recognize several important dynamics:

- The plan sponsors that contract with Medicare also contract with employers and therefore have much more market power than Medicare alone. For example, Express Scripts, a major player in Medicare Part D, provides drug coverage for 85 million Americans. CVS Caremark and Optum Rx also have substantial national market share and are highly sophisticated negotiators and managers of drug costs.

- A single drug plan undermines the government’s negotiating power. A single drug plan means the patient has no choice. Therefore, the seniors, patient advocates and, yes, drug company lobbies would effectively compel coverage of virtually all drugs. If the Secretary could not limit access to particular products, on what basis could she truly negotiate?

- How would the Secretary negotiate? Would the Secretary personally negotiate with over 150 manufacturers for more than 2,000 products in nearly 200 therapeutic classes? Secretarial negotiation for one drug undermines private plan negotiations for all other competing drugs. Whom does the Secretary represent in negotiations — plans, patients, or providers?

The ultimate impact of Secretarial negotiation is to centralize decision making within the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). CMS would become the locus for lobbying campaigns where decisions would be made through a political prism.

This is precisely what the Left desires. It would gain the control over the pharmaceutical industry that it now foists upon the hospital industry, physicians, and a slew of other groups that are directly paid by Medicare. CMS does not negotiate with these groups to determine the terms and conditions of their payment. Rather, it administers a raft of detailed fee schedules and reimbursement formulas that are dictated in statute and interpreted by the agency through complex rules, regulations, and program memoranda.

Indeed, the Medicare Part D drug benefit is an island of negotiation in a sea of administered prices.

In February, the Obama Administration’s FY 2017 Budget proposed empowering the Secretary to negotiate with pharmaceutical manufacturers for high cost drugs and biologics. However, the Administration’s own actuary assessed this policy proposal as providing ZERO savings. The Congressional Budget Office has similarly stated that “Risk-bearing private plans have strong incentives to negotiate price discounts for such drugs and that the Secretary would not be able to negotiate prices that further reduce federal spending to a significant degree.”

The real risk to the pharmaceutical industry is not a legitimate negotiation per se — Medicare has already hired powerful and able contractors to fulfill that function effectively. Rather, the risk is establishing an arbitrary price control that does not reflect market value.

Most troubling, CMS does not require new statutory authority from Congress to establish such a pernicious pricing system. It could use its authority under Obamacare’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI). Unlike most demonstration projects, which waive discrete sections of the statute and are time-limited (e.g., 3 years) and limited by population and geography (e.g., 5 sites or no more than 200,000 beneficiaries), CMMI may waive the entire Medicare and Medicaid statute for any “Phase 1” demonstration project.

This means the project could essentially be national (exempting Delaware, for example) and last for years. Thus, nothing would prohibit the Secretary from testing the Canadian or Veterans Affairs price of Sovaldi, all cancer products, and a host of other high cost drugs for Medicare beneficiaries residing in the 20 largest statistical areas for five years.

WHAT CAN BE DONE TO PROMOTE GREATER EFFICIENCY IN MEDICARE PART D?

Policy makers are searching for solutions to the rising political invective on pharmaceutical prices. A good place to start would be to examine the distortionary policies Congress enacted to address drug pricing in the first place.

One example is “Medicaid Best Price.” As a condition of participating in the Medicaid program, manufacturers must pay rebates to states. This rebate equals the greater of 1) 23 percent or 2) the “best price” negotiated in the private market, plus any price increase exceeding inflation from date of launch. In a series of scathing government reports dating back into the early 1990s, the Congressional Budget Office and the Government Accountability Office documented that imposition of “Medicaid Best Price” resulted in smaller discounts in the private sector and may have contributed to higher launch prices of new products.

Manufacturers negotiate discounts to the customers in order to gain something of value in return — better access to their patients, improved market share, etc. But if they have to provide that same low price to a government program that can deliver no such value, they will have little incentive to provide substantial discounts.

The massive expansion of the Medicaid program by Obamacare — adding 14 million beneficiaries, increasing the program by 25 percent — compounded the distortionary aspects of this policy. Secondly, 340B hospitals that now account for one out of every three hospitals, also utilize the “Medicaid Best Price” scheme to determine their mandated discounts. And that program has grown geometrically in the last five years.

Not everyone can get the lowest price in the market. Requiring huge swaths of the population to be provided the lowest price when they can provide no market benefit in return has undoubtedly resulted in higher prices to other individuals and groups.

Congress made the right decision in 2003 when it enacted a provision added by Ways and Means Chairman Bill Thomas (R-CA) to exempt Medicare Part D plan price negotiations from the “Medicaid Best Price” formula. The Congressional Budget Office scored that provision as saving Medicare $18 billion over 10 years because it encourages manufacturers to negotiate substantial discounts without penalties.

Congress should similarly repeal best price in its entirety so that more consumers may benefit from aggressive negotiations that would surely follow in a more market-based dynamic. This is a much better solution than enabling government bureaucrats to determine prices in an arbitrary matter that would only empower Washington but not hold down costs in the long run.