The Art Of Optimizing Small Biotech Market Caps – From Scientific Dreams To Strategic Reality

Moderated and edited by Wayne Koberstein, Executive Editor

As the sun cast a rosy glow over the city’s horizon, bathing us in dawn light through the wide windows of our meeting room, a small group of company executives and investment experts shared breakfast and chatted before taking up the business at hand. Their purpose here: Trade insights across the table into how small biotech companies can achieve the best possible market capitalization at every stage of their development.

As the sun cast a rosy glow over the city’s horizon, bathing us in dawn light through the wide windows of our meeting room, a small group of company executives and investment experts shared breakfast and chatted before taking up the business at hand. Their purpose here: Trade insights across the table into how small biotech companies can achieve the best possible market capitalization at every stage of their development.

As the panelists subsequently confirmed, factors that determine the valuation of such companies vary from straightforward and objective to unpredictable and highly subjective — making for a fascinating discussion whether you are an expert or a lay person in life science investment. We held our roundtable in San Francisco during the confluence of industry events surrounding the JP Morgan Healthcare Conference in January 2014. Our intended audience was not in the room with us, but consists of our readers, essentially all of whom are affected by the issues we discussed.

The panel’s actual makeup of people resulted partly by plan — invitations went out to a select list a month in advance — and partly by accident: who among the invited wished to and were able to answer our call. We had targeted a range of people reflecting the leadership of small and large Biopharma companies and investment firms. As it happened, the panel was evenly divided between the company and investment sides: Around the table were five leading investors, four small-company chief officers, and one head of business development for a large biotech known for its long line-up of successful partnerships and acquisitions.

The following is an edited transcript of Life Science Leader’s Optimizing Small Biotech Market Caps roundtable.

Chief Editor Rob Wright welcomes the panelists, and they begin to define the objective and subjective factors that determine a small biotech’s valuation from its earliest stages.

ROB WRIGHT: Good morning. Thank you for coming. One of the most valuable things we have in our lives is time, so I’d like to make sure I thank you for taking the time to be with us today. We wanted to do something more interactive than bringing a bunch of people together and having a separate group talking up on the stage. We also want to develop this discussion into future editorial that our readers find valuable. Now I’m going to turn it over to Wayne. But first let’s go around the table and have everyone introduce yourself.

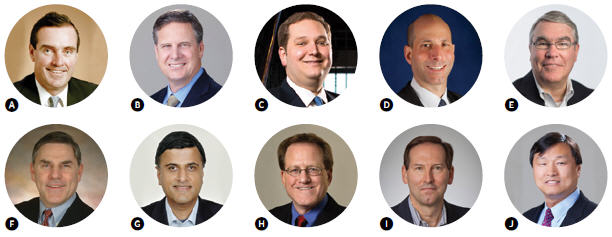

The panel answers the roll call:

A Dennis Purcell Senior Partner of Aisling Capital

B Rich Vincent CFO of Sorrento Therapeutics

C Jacob Guzman Corporate Client Group Director at Morgan Stanley

D Allan Shaw Managing Director at Life Science Advisory Practice, Alvarez & Marsal LLC

E Ford Worthy Partner & CFO of Pappas Ventures

F Kenneth Moch President and CEO of Chimerix

G Jaisim Shah CEO of Semnur Pharmaceuticals

H William Marth CEO of AMRI

I George Golumbeski Senior Vice President, Business Development at Celgene

J Henry Ji CEO of Sorrento Therapeutics

WAYNE KOBERSTEIN: Great to see you all here this morning. My top priority today is to elicit your thoughts on three central questions:

What are the most important factors in how the market cap for small biotech companies is calculated?

How are the companies affected by the value of their market cap at key stages in their development?

What actions can companies take to achieve/optimize their market cap at those key stages of development?

I had the idea for this meeting mainly because I don’t know what the answers are to those questions. I don’t know what goes into determining the market cap and valuation of a biotech company, either private or public, at the small-cap level. I can guess and observe like any other layperson, and I imagine that a lot of the answers have to do with subjective factors. But, that’s fine, we can discuss what those are. Why is valuation important? What should it be in an optimum world? And then, how can companies actively work to reach that optimum valuation market cap?

So, let’s start, clockwise to my left. Dennis, can you begin with a general answer to the first question — what factors determine a small-cap company’s valuation, from start-up on?

DENNIS PURCELL: It starts with supply and demand. If you’re starting a company, the more options you have, the better the valuation will be. It’s really important to get the right people around the table at the beginning because the valuation going forward is largely set based on insider participation — whether the insiders have enough money and whether they will support you and your strategy. You can’t start by doing present value calculations or following set formulas. It’s really more of an art than a science right at the beginning.

KOBERSTEIN: More art than a science — I suspected that. Can you follow from that, Rich?

RICHARD VINCENT: From the very early stages, before you can even attract VC money, you’ve got to step back and figure out how you get a company off the ground. In San Diego, we see a lot of start-up companies, and it’s very difficult for many good companies to secure seed money. We often have to go to friends and family and some of the angels in town or in other major cities in the bay area or on the East Coast. We actually try to avoid the question of valuation with some of the seed money we raise, by offering convertible notes. The notes will typically carry a standard 6 to 8 percent interest rate and some sort of discount factor toward the next financing (typically a VC-led round whereby the VCs lead the due diligence effort). So we take the valuation question off the table at that stage and defer until the VCs or other larger investors invest. A lot of the seed people like that, because then they don’t have to do all the hard work the venture folks do to determine the quality of an asset.

KOBERSTEIN: What about thereafter, once you get past that very early stage?

VINCENT: Then you follow the lines that Dennis mentioned: it’s all about supply and demand. We do that by being tactical across the spectrum of the business, whether it’s bringing in the right management team, board, and opinion leaders, or IR (investor relations) firms to make sure the company is doing all of the qualitative things, meeting its milestones, executing well in all phases of the program.

KOBERSTEIN: So the seed money comes in when the new company might have a scientific premise but before proof-of-concept?

VINCENT: It could be pre-proof-ofconcept because oftentimes the VCs won’t come in until there’s some sort of proof-ofconcept, whether it be in the right species or in man. It certainly challenges the niche area strategy among start-ups in today’s environment. You often hear that startups are the backbone of the country, but it’s very difficult for them to raise money — much more difficult than people realize.

PURCELL: Private companies are much more efficient than public companies. Is Intercept worth $6 billion more today than it was on Friday? I don’t know. If you were a big shareholder in Intercept and it was a private company, you probably would have held it at cost or marked it up a little bit, but as a public company, it is now worth $7 billion.

JACOB GUZMAN: I see a lot of companies, and I’m a finance man, not a scientist, so I look at a lot of fundamental issues of value outside of science. In some ways, the science part is irrelevant to me. Building a company, developing a management team are important fundamentals — Dennis made a very good point. I always look at interesting facts about a company, something that others may overlook, for example, why a certain person is on the board of a small, little company in West Philadelphia. What does this successful former large pharma CEO see in this specific company? There must be something there; this intrigues me. We also seek out the best CEOs, in whom we look for a mix of businessman and scientist — the businessman to go out and raise the money; the scientist to explain what they are trying to sell. We meet a lot of people who are too much of one, and we can’t understand what they are trying to sell. And we also meet a lot of people who are too much the other, and we can’t understand what they’re trying to sell. In the end, the most successful companies we’ve dealt with have had an interesting team, successful science, and have been able to effectively explain things to us. This makes me interested in learning more and developing a strong relationship.

SCIENCE, BUSINESS, & ART

The conversation takes a turn toward the qualitative assets needed in a young company to maximize its value during the formative fundraising stages.

KOBERSTEIN: You raised an interesting point about the scientist-business executive and the various personalities you encounter. So it’s not just a matter of the prestige of the scientist or the purported value of that person’s work, but one factor is the ability of that person to interact with and understand the business side, right?

GUZMAN: Absolutely. Even though someone believes in the science, they might not be willing to invest in a particular person because they don’t know how many other people will understand what the CEO is talking about. Investors don’t want to be the only ones in the pool. The CEO won’t get very far without being able to get their message across in a clear and concise manner.

KOBERSTEIN: Allan, we have been talking mainly about starting up a company and the role that valuation and market cap plays at that stage. What are some other factors that can influence it at that point?

ALLAN SHAW: I’d like to build off the comment Dennis made, “It’s more of an art than a science.” There are many qualitative considerations that you need to take into account. We touched on the management team. There is also the therapeutic focus. Like platform shoes, therapeutic areas or targets go in and out of fashion; cancer is the flavor of the day right now. Also, time-to- market or development timelines are not inconsequential. There is increased emphasis on orphan drug development and focused drug therapies right now, and developers are trying to bypass Phase 3 studies and use Phase 2 trials as the pivotal stage studies to achieve registration. To underscore these dynamics, the spirit of the times is very important. Right now, everyone’s taking capital market happy pills, and the word risk seems like a distant dream. That has a real psychological impact on access to capital and the underlying valuations at the end of the day. When everyone is feeling good about themselves, the relative valuations will inevitably expand — a high tide raises all boats, and a low tide lowers them.

KOBERSTEIN: So one factor is very general, just the environment at the time.

SHAW: Absolutely, and it also strikes me that there’s a disconnect between valuations of established companies that have been operating in this space for a period of time versus some nouveau companies that have recently come to market. It speaks to some of the qualitative differences, because the new companies haven’t had time to disappoint yet. By and large, they haven’t had any notable clinical failures. Some of these qualitative factors transform themselves into the market valuation.

KOBERSTEIN: Yes, I encountered a relevant situation yesterday. I interviewed the head of a company that had basically reinvented itself after a Phase 3 failure. It’s been in business for 12 years, but now it’s like a new company, with new management and all new products in new areas. I asked him, “How does that affect your valuation?” He said, “We are really undervalued because of what happened in our past, even though it has nothing to do with what we’re doing now.” He said when the company goes public, its current state may be a factor, but at this point it’s not boosting the value.

KOBERSTEIN: Yes, I encountered a relevant situation yesterday. I interviewed the head of a company that had basically reinvented itself after a Phase 3 failure. It’s been in business for 12 years, but now it’s like a new company, with new management and all new products in new areas. I asked him, “How does that affect your valuation?” He said, “We are really undervalued because of what happened in our past, even though it has nothing to do with what we’re doing now.” He said when the company goes public, its current state may be a factor, but at this point it’s not boosting the value.

PURCELL: No company proceeds like you think they’re going to proceed. We were an investor in Intercept in a different indication than the one it announced. (Lots of laughter.)

FORD WORTHY: From the venture perspective, valuation is very much an art, as Dennis says. There is no net present value, discounted cash flow analysis typically done. But it’s all about looking at other companies in the market — both companies that you’ve financed yourself at similar stages as well as other companies for which you have good data — and comparing, through a myriad of adjustments for the various risks involved, how a particular company compares with a pool of similar companies. Your initial question has the word “calculated,” as in how market cap is calculated, but ultimately, it’s really negotiated. You start with the best information that you can collect at that stage, looking at comparable companies, and then it’s a negotiation.

KOBERSTEIN: I used “calculated” somewhat as a red herring, knowing I’d probably get a reaction. But when you say valuation or market capitalization, it does sound like something a financial person sat down and calculated, with formulas and so forth.

SHAW: We could even have an interesting conversation about “what is market cap?” What do you mean by market cap? Is it simply the price of the share, the last price paid times all fully diluted shares outstanding, or is it ultimately the value of the company — what someone would buy for the whole enterprise?

KOBERSTEIN: Right. So there are the tangible assets, and then there is the actual price it might be purchased for, which could include intangibles.

EXPECTATIONS MANAGEMENT

Do some companies get ahead of the game in boosting their market caps based on unrealistic hopes about later stages of development? Or is “judgment” an inevitable and necessary part of early investing?

KOBERSTEIN: There has been much public discussion recently about a few companies that have achieved enormous market caps based on early, conditional approval in one narrow indication along with a strategy of subsequently expanding approved indications for the same product into much larger markets. It seems market cap can sometimes grow very large for a company based on such expectations, but when problems arise, say, with safety in the follow-up trials, the valuation can fall quickly.

PURCELL: Well, that’s why some of those companies have a very high price to yearnings! (All laugh.)

KENNETH MOCH: If you look at the theory of the capital asset pricing model, stock prices are the present value of future earnings, discounted for risk. If you project what you believe are relevant future earnings, you have to include the exogenous discount rate of the markets, right? At least to some extent, you can watch the water rise and fall based on those internal and external factors, and it kind of makes sense. But nobody can really predict the future earnings of a product that’s not yet marketed, so the whole thing is a series of judgment calls. That’s the way valuations have evolved — with judgment a key aspect of it all. Somebody said to me recently, “There’s no such thing as behavioral economics; all economics are behavioral.” So the pricing model fits into the capital asset model, as well.

KOBERSTEIN: How different is valuation for life sciences companies versus companies in other sectors, then? Is it more subjective or less subjective than in other sectors?

JAISIM SHAH: I can speak to fundraising in innovation, including the judgment aspect, because we raised $30 million Series A less than six months ago. We had no angel funding. We actually had no product. (Everyone laughs.) We had an idea, to address a hot topic raging through the country: the compounding mess, which had led to about 700 fungal disease infections and 100+ deaths from a New England pharmacy and other compounding pharmacies. We decided to focus on chronic back pain, and to come up with a formulation that will address all the issues causing pharmacies to compound.

We talked to only a few venture funds, and they gave us a term sheet. There were only three things that anyone wanted to know: One, can you price this product and get reimbursement? Two, was there a clinical rationale? That was a challenge, because there are no drugs approved to treat these patients; all drugs currently treating the condition are used off-label. And three, would there be a company that would have interest in partnering with us? We did no press release on the fund-raise; we really wanted to stay under the radar screen. We just filed a Form D [Notice of Exempt Offering of Securities, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission], and someone in the press did a write-up about this, saying this “stealth biotech” came out of nowhere, raised $30 million, and got really marquee firms to invest in it. We still haven’t disclosed publicly what we are working on. (Everyone laughs.) But we’ve had companies contact us, ask for diligence decks [company slideshows], and nonconfidential presentations. We plan to be in Phase 2 this year. It gave me hope that anything is possible these days. (Laughter.) This is the right opportunity, and we have, of course, a really good team. I have worked and closed on other start-ups like Elevation Pharmaceuticals, partnerships, and acquisitions, and my cofounder and chair, Mahendra Shah, has founded and sold four other companies.

We talked to only a few venture funds, and they gave us a term sheet. There were only three things that anyone wanted to know: One, can you price this product and get reimbursement? Two, was there a clinical rationale? That was a challenge, because there are no drugs approved to treat these patients; all drugs currently treating the condition are used off-label. And three, would there be a company that would have interest in partnering with us? We did no press release on the fund-raise; we really wanted to stay under the radar screen. We just filed a Form D [Notice of Exempt Offering of Securities, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission], and someone in the press did a write-up about this, saying this “stealth biotech” came out of nowhere, raised $30 million, and got really marquee firms to invest in it. We still haven’t disclosed publicly what we are working on. (Everyone laughs.) But we’ve had companies contact us, ask for diligence decks [company slideshows], and nonconfidential presentations. We plan to be in Phase 2 this year. It gave me hope that anything is possible these days. (Laughter.) This is the right opportunity, and we have, of course, a really good team. I have worked and closed on other start-ups like Elevation Pharmaceuticals, partnerships, and acquisitions, and my cofounder and chair, Mahendra Shah, has founded and sold four other companies.

KOBERSTEIN: That was an interesting case.

WILLIAM MARTH: I’m rather new to this forum, so if you think I can top not having a drug or a rationale and raise money then . . . (Everyone laughs.)SHAH: I think it’s more about your 12+ years at Teva and growing the American companies from $2 billion to $12 billion.

MARTH: I’ve had some experiences, and I’ve found the science is important but the strategy is critical. If there isn’t a strategy, if you cannot articulate what it is you’re trying to do and how you’re trying to do it, and what the endpoint is, it is very difficult to get investors. I started in the early days at Teva, back when we were $350 million here in the U.S., and we grew it to $10.5 billion here and $22 billion globally by the time I retired last year. We started out talking to a lot of people who really didn’t want to listen to us in the beginning, but we had a strategy, and people understood the strategy. We could articulate it, they could understand it, and so those who invested in us did very well. And those who didn’t, wished they’d invested. But it’s really critical; science needs to be linked with the strategy, above all other factors.

KOBERSTEIN: Is there a process of critiquing the strategy? When you have a strategy, do you typically encounter people who are skeptical and try to take it apart?

MOCH: The investors can talk to that better than the company side. Our job is to create the vision, and their job is to tell us why it’s wrong. (Laughter.)

KOBERSTEIN: Good point.

MOCH: That’s the ying and the yang of the business, of investing and creating, right? It’s about trying to define the inflection point between the overt optimism of the CEOs and the “I’ve been through this before and lost money” pessimism, which is not illogical, for the investors. Some people say, “Okay, I see your vision at this price, because that’s where I think I can make money.” Dennis can certainly speak to the process. Everybody comes in with a billion-dollar idea, and your job is to say, “I’ve seen this before.”

"I always look at interesting facts about a company, something that others may overlook."

Jacob Guzman, Corporate Client Group Director at Morgan Stanley

PURCELL: We look at 700, and we do 10, and a few work. It’s a hell of a business. (Everyone laughs.) George sees them, too, at Celgene. As the CEO, you’re just trying to build your company, and one of the elements of strategy is to understand the world around you, not just to operate in your little niche. Too many times people come in, and they just don’t see the big picture.

KOBERSTEIN: So you can’t fault any company for going out and saying, “We’re going to do this.” It’s really up to the investors to judge.

GEORGE GOLUMBESKI: Recent history tells us that whatever the market climate, how high is the tide or how low the tide is, not all companies go up or down exactly the same. I’m trained as a scientist, I’m a long-term BD guy, and though I don’t have the sophistication in market theory, my view follows from everything I’ve seen working with many small companies. In some ways, my business is really not dissimilar from the investors’. We have all these companies come to us. We invest in some of them, we buy some of them, and we are very motivated to work with them because we want the drugs, not the equity appreciation. Some are going to fail, and some are not going to fail, so you have to have a portfolio because that’s the business we’re in. But all these market reactions and contortions!

People understand — investors, the market — that developing a real, innovative, safe, and efficacious drug is very difficult, and any hint that there’s a real drug in the works, the prices spike. But suggest there may not be a viable drug, they crater. Just look at recent events: We do a deal with OncoMed. That’s a good company. We’re very happy to have gotten a deal. The stock price goes up 100 percent in one day, but the data haven’t changed. Or we pay a milestone to Epizyme, and the stock goes up 40 to 50 percent in one day. It’s because people believe a drug will come out of the deal. Of course, I would also say, historically, a deal with a large, respected company validates to the market that the smaller company has a real drug in development.

MOCH: And it attenuates the perception of risk. Again, if you go back to the simple capital-asset pricing model, such a deal actually changes the perception of risk, and so the value should change.

GOLUMBESKI: But companies going it alone, like Ariad or Sarepta, experience the most volatility, even though many people are eager to believe in their products. Over the long term, I believe the real value will become clear, but at any one moment there’s a hell of a lot of emotion out there.

VALUATION VALIDATION

Partnerships and other deals with major pharma and biotech companies may reinforce trust and perception of value in a company’s clinical development potential. But the pool of candidates for such deals is shrinking, raising the stakes of success or failure and amplifying stock-price volatility.

PURCELL: George, you’re probably the most active guy in the industry right now. What’s your total view of the opportunities presented, deep dives, number of deals, and so forth?

GOLUMBESKI: Oh, that’s a really good question. We have a process that’s probably not disparate from other large companies. An amazing amount of information comes in from partner seekers, from writing us letters to calling a board member. We get hundreds of company disclosures, but out of every 100 that come in, we may decide to ask for more information from 10 to 15 of them, maybe sign CDAs (confidential disclosure agreements) on eight or 10 of those, and probably end up doing due diligence on only three or four. My group tries not to burden the rest of the organization with too many projects because, although our job is to do deals, we’re going to look deeply at something before involving the clinical people, finance people, or the top people. So we usually have a fairly high rate of attrition before that stage.

PURCELL: Have you ever eliminated one, in retrospect, that you wish you hadn’t?

GOLUMBESKI: I’m sure it’s happened, but I honestly can’t think of one off the top of my head. We try to set the filter wide enough, if you will, so that we don’t have that happen. So far, I believe our selection process has mostly gone well. But going into the next two to three years, I’m not concerned at all that Celgene will run out of financial resources, corporate resolve, or CEO and board support, which I must say is exemplary. I’m just worried that the assets are getting harder and harder to find.

PURCELL: Versus five years ago?

GOLUMBESKI: In my mind, no doubt.

PURCELL: No doubt.

GOLUMBESKI: I’ve seen a lot of data, bad and good. If I put my time at Novartis and Celgene together, I’ve had the privilege of seeing everything in oncology for 13 years now — everything from early stage to on-market — and there were always some interesting things going into the clinic. Now, there are a few drugs out there, but the predictions for future assets are not robust.

MOCH: Is that because of the number of new technologies and products or because of the prices of new technologies and products?

GOLUMBESKI: More of the former — the sheer number. Up to now, we’ve been smart, fortunate, blessed, however you want to look at it, but we’ve recruited some really great partners: OncoMed, Epizyme, Agios, Quanticel, and so on. We could do five more deals a year if we could find the companies.

KOBERSTEIN: You mean companies with a bona fide drug in development, from what you’ve said. Is there a standout criterion or factor that helps you select them out of the crowd of contenders?

GOLUMBESKI: We probably all have our own biases as with our training and background, but there’s no doubt in my mind that in the end, it is all about the team, the data, and the molecule. Even the best team cannot turn a bad molecule into anything, and a bad team can really destroy a good molecule — you really need both, and some luck. What drives us to invest? It’s data and a belief that the data will translate to a meaningful drug. And I think over time, you get a meaningful drug, and then one realizes value. In the short term, investors can make tons of money on premature excitement about a drug. I’ve seen data about companies that never produced anything but made money anyway. But it’s not just about money. In the end, we feel we only really succeed when we get new drugs to patients, and the patients benefit.

Right now, everyone’s taking capital market happy pills, and the word risk seems like a distant dream.

Allan Shaw, Managing Director, Life Science Advisory Practice at Alvarez & Marsal LLC

Thus ends Part One of The Art of Optimizing Small Biotech Market Caps editorial roundtable. Part Two of the discussion will appear in our next issue, covering the effects of valuation and market cap on companies as they grow and ways they can optimize their value at every stage in their development. More case studies and experience-based lessons arose in the remaining half of this thought-leader discussion, along with worries about drug-candidate shortages and unsustainable investment cycles. Part Two shows the panel detailing the importance of managing company and scientific communications, establishing relationships, winning patientadvocate support, spending cash carefully, and other actions companies can and should take to optimize their value and growth.