Why And How To Close The Gender Gap In The Life Sciences

By Camille Mojica Rey, Contributing Writer

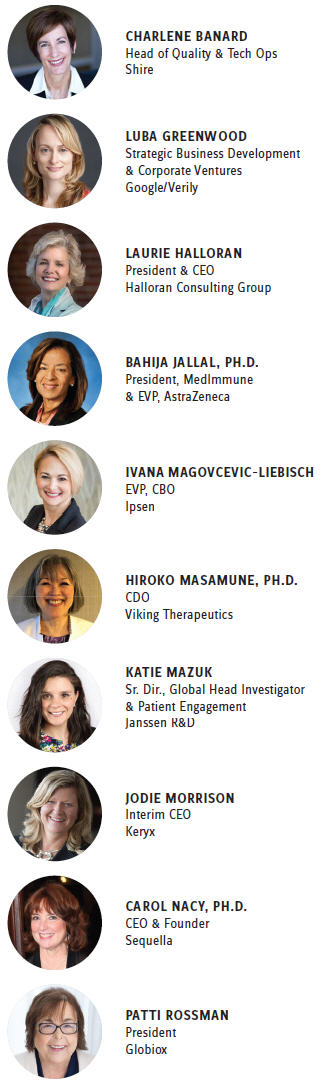

Follow Me On Twitter

Statistics on leadership in the life sciences industry indicate a disturbing trend for women. They enter the industry in equal proportion to men but account for just 24 percent of C-suite positions and about 14 percent of board-level positions. That’s according to a 2017 report by The Massachusetts Biotechnology Council (MassBio) and the executive recruiting firm, Liftsteam, based on surveys of 850 professionals and 70 companies within the state. Similarly, Women in the Workplace 2017, a national report based on surveys of more than 70,000 employees and 222 companies by McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.org, found 52 percent of entry-level positions at pharmaceutical and medical products companies are filled by women, and 22 percent of C-suite positions are filled by them. The MassBio report says the number for biotech boards is probably closer to 10 percent. GSK’s Emma Walmsley made headlines in 2017 when she was named Big Pharma’s first female CEO – and was given a pay package worth 25 percent less than her predecessor’s. Walmsley’s promotion translates this way:

1 percent of Big Pharma CEOs are women.

1 percent of Big Pharma CEOs are women.

These statistics serve as indicators of what prospects are like for women looking to advance their careers in the life sciences industry. They are also a call to action for the industry, according to industry leaders. Women leaders, in particular, know the gender gap in life sciences is a complex problem with roots in larger societal issues, from how we raise our children to how our culture defines success. Still, women with leadership roles in the pharmaceutical industry in particular say it is imperative that the problem be addressed — by both men and women — for the sake of the industry’s future. That’s because, if the current trend of women leaving the industry continues, the gender gap problem will become a worker-shortage problem and reduce innovation that is vital for industry growth.

“Right now, there is an equivalent number of women and men coming into the industry at entry-level, but they do not climb the ranks at a consistent rate. And, perhaps more concerning, women appear to leave the industry altogether,” says Jodie Morrison, interim CEO at Keryx and a cofounder of MassBio’s Gender Diversity Initiative. According to the MassBio/Liftsteam report, the most rapid loss of women from the pipeline — nearly a 20 percent decrease in the participation of women — is between manager and mid-level leader. “You can foresee this causing a major staffing issue if this trend continues,” Morrison, says. Patti Rossman agrees. “We have to work to close the gender gap because it is draining on the industry,” says Rossman, who is Founder and President of consulting firm Globiox. She is organizing the inaugural Life Science Women’s Conference in Austin, TX in August 2018. “We’re hoping women will come together in a collaborative environment, learn how to help each other, and discuss actions that can be taken to close the gender gap.” She also says men and women need to do more on this issue. “When life sciences companies in the U.S. have a hard time finding workers, that’s really a hardship for the industry. It drives up costs and requires that industry find workers outside the U.S.”

The impact of the lack of diversity across many sectors has been well-studied. According to a 2004 study in the Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, diverse groups of problem solvers outperform even groups of high-ability problem solvers. Problem solving is the focus of the life sciences industry. “We need to surround ourselves with people who challenge us — not just those who look different from us but who think differently than we do,” says Bahija Jallal, Ph.D., president of AstraZeneca’s R&D arm, MedImmune. Jallal says the first step in working toward closing the gender gap is reframing the way we talk about diversity and inclusion. “We’ve got to change the narrative around diversity. Diversity is not something that is simply ‘good to do.’ The data bears it out — diversity is good for business. So, as an industry, we need to embrace this mantra and recognize that when we bring the right people to the table with diverse backgrounds and thought processes — regardless of their looks and beliefs — we will be more successful.” Charlene Banard, senior VP of global quality at Shire Pharmaceuticals, says diversity breeds better solutions. “When you think about solving problems in our field, we solve them through cross-functional teams that bring diversity of thought. That makes sense on a large scale as well. It brings shareholder value when we have diversity of thought. Fundamentally, we learn from each other and the experiences others bring to the table. If we are at the table with people of similar backgrounds, the amount of learning is going to be less. We need to fix the issue. But, that is easier said than done.”

Luba Greenwood, Strategic Business Development & Corporate Ventures, Google/Verily

Hiroko Masamune, Ph.D., chief development officer at Viking Therapeutics says the life sciences industry is facing the same challenges that other sectors across the nation are facing. “Most fields are heavily dominated by men in C-level positions. I don’t think this is necessarily by design, but not as many women get promoted to those positions. So, there is a smaller pool to pull from.” She also says that smaller biotechs tend to hire CEOs who have previously held that position at other companies. “It’s harder for someone new to break through.” Still, women leaders insist that there are things individuals, companies, and the industry can do to affect incremental change that can, however slowly, close the gender gap. “It’s tough to figure out why this is happening at a macro level, so we need to start looking at the micro level,” Morrison says. Each individual and each company must study the problem locally and take action.

Women leaders in biopharma are taking action on many levels. First and foremost, Laurie Halloran, president & CEO of Halloran Consulting Group, says they advance the cause of gender equity by being successful and effective at their jobs. Women who decide to get involved in gender issues have to strike a balance between advocacy and building a reputation for being great at what they do. “Just being in your role and being public about it is sometimes enough. Sharing your perspective and sharing your story makes a difference.” Carol Nacy, for one, views herself as an accidental advocate. “I actually never have thought of myself as a ‘woman’ scientist, just a scientist,” says Nacy, who is cofounder, CEO, and chairman of the board of directors at Sequella. Nacy says she is often asked to speak about gender gap issues. “I find it a little awkward, but I think it is important for young girls to see that there is a path forward.”

Many women who spoke to Life Science Leader say they have seen little change in the gender gap, including pay differentials between men and women, in their professional lifetimes. However, they also say the time is at hand for accelerated change, thanks, in part, to the #MeToo movement. “I really think there has been no change because this issue has not been brought to the attention of society,” Rossman says. “In the time of #MeToo, this is the time and place for these issues to be brought up.” She also points out that the gender gap is even worse for women of color. “We need to do something about that, too.”

PERSONAL RESPONSIBILITY

Women who have defied the odds and are in leadership positions in the life sciences industry feel compelled to address diversity issues, starting with their own families. Katie Mazuk, senior director, global head investigator and patient engagement at Janssen R&D, does what she can to share her own love of math and science with her young daughters. “The disconnect between girls and STEM subjects happens really early in pre-K and kindergarten. I feel a personal responsibility to cultivate a passion for science and math in my daughters and other young people that I have influence over in my life.” Mazuk says she also donates to nonprofit groups, like Girls Who Code, as a way of supporting efforts to close the gender gap in STEM fields in general and in the life sciences in particular. Halloran has teenage children and is conscious of serving as a role model for them. “I have spoken to my child’s high school class on entrepreneurship. I also took him to an open house at Vertex Pharmaceuticals when he was in sixth grade to see what it’s like to be in a biotech company. You have to look for the opportunities.”

Morrison, for example, serves on the STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, mathematics) task force in Wakefield, MA, as a local biotech representative. “I think it’s important to make sure our schools are exposing girls early to these subjects and guiding them in the direction of STEM professions.” In addition, Morrison is on the CDC committee for Mount Holyoke College as the life sciences representative to encourage women entering the workforce toward roles in STEM. Halloran says the gender gap is not going to close quickly, but these kinds of activities will add up to big change, especially in terms of girls’ perceptions of STEM careers. “They don’t see gender as a big barrier as I did. There is a lot of positivity coming in the next generation. We just have to make sure we nurture it,” she says.

Luba Greenwood leads strategic business development and investments at Verily, an Alphabet life sciences company in Cambridge, MA. Greenwood is passionate about mentoring young women and closing the gender gap. “Teaching life sciences and entrepreneurship at the Boston University School of Law, I encourage women to pursue careers in the life sciences and enjoy staying in touch with my former students.”

MENTORING, NETWORKING & VISIBILITY

One of the most common ways women leaders in the life sciences work to close the gender gap is through mentoring, networking, and being professionally visible. Halloran, for example, is on the board of New England Women In Science Executives Club, a networking group designed to help women in leadership positions find peers and mentors. Halloran says she has a lot of interaction with women who are new in C-level roles. She acknowledges the level of intimidation they might feel, but impresses upon them that there is no need to be afraid to speak up and be themselves. “It’s definitely still a man’s world, but there’s a need to elevate yourself. You have to be confident, build relationships, and self-advocate.” Morrison says she spends a lot of time mentoring young women and meeting with women in the industry to discuss what they want to do next, including women from entry-level positions to management and board members. “I am proud to say that I’ve never turned down a meeting from a woman in the industry looking for advice.” Mentoring is something that professionals can benefit from at any stage of their careers. After 30 years in biotech and decades of mentoring others, Banard has been assigned a mentor of her own as part of the International Womens Forum’s year-long fellows program. “It’s been a long time since I had a mentor other than my boss.” Banard says it is also important for leaders, especially women, to be visible. “The more we have exposure to executive committees and boards of directors, the more tangible our participation becomes and the more likely such a role is to become an aspiration.”

CORPORATE RESPONSE

How the leadership of individual companies responds to the gender gap at this moment in time largely depends on their companies’ demographics. “More than half of our senior management are women, so we are very aware of keeping the gender gap closed at our organization,” Masamune says. “My company makes a point to hire women and pay them salaries that are equivalent to men at the same level.” Likewise, Greenwood says, having women in leadership positions is key. “My company makes sure to hire talented women, most importantly in leadership positions. It is also a high priority for the company to offer formalized mentoring to the more junior women and make the path to get to a leadership role very transparent.” The burden is greatest to lead by example on this issue for those women who run companies, Banard says. “We can’t be lazy. When we hire people, we need to be specifically looking for more diverse candidates. People like ourselves have networks that are similar. We need to look for different networks where we can get people with diversity of thought and background to be potential candidates. If we want to change it, we have to work at it.”

Morrison believes one way to work on the problem is to gather data on why women leave companies. “Individual companies need to evaluate the departure of women and the core functions of women within the organization. It’s important to ask the right questions in exit interviews.” Morrison has had a long history of working with human resources departments in biotech companies on this issue. More recently, at both Keryx and at another local company, she has had exposure to ”dashboard methods.” These are large-scale metrics for the companies that highlight diversity among the workplace, based on roles, promotions, new hires, etc. Morrison says Keryx, which currently has a majority female executive team, has historically evaluated functional areas along gender diversity and employed active efforts to ensure that any gross inequality is rectified. For example, the company’s HR leadership recently took a look at one area and noted a disproportionate number of male leads and shifted to a core focus of bringing on more women.

Ivana Magovcevic-Liebisch, EVP, CBO Ipsen

Ivana Magovcevic-Liebisch, EVP, CBO (chief business officer) at Ipsen, believes companies need to change the way they think about employee support. Magovcevic-Liebisch has sat on a number of panels at Harvard, the Museum of Science, and various business conferences discussing how to get women into C-level and board positions. “We need to flip the saying ‘behind every great man is a woman’ to ‘behind every great woman is a man.’ It’s important for men to also take a step back and be comfortable with that.” Men also have to be comfortable supporting women, Rossman says. Women should guard against demonizing their male colleagues, especially in light of the #MeToo movement. “We need good men not to be afraid to mentor women,” she adds. Morrison says men have to be part of the solution. “Addressing the gender gap issue can’t be a female-only-led initiative. Men need to be involved, too. When we position it as a focus on the growth potential from an industry perspective because teams will not be able to be staffed if this continues, it becomes obvious it is a global corporate issue, and not just a women's issue."

GUIDING INDUSTRY PRACTICES

Morrison is among those pushing the industry to accept best practices regarding increasing diversity. Working with executives in the industry to assess guiding principles, MassBio's Gender Diversity Committee wrote an open letter to the industry, which coincided with the 2017 JP Morgan conference. The letter was signed by over 100 biotech executives when issued, and it received hundreds of additional signatures once published. This letter included the "Top 10 Best Practices for Increasing Gender Diversity in the BioPharma Industry." MassBio and Liftstream followed with the life science survey that looked at diversity issues in companies. "This inventory allows us to see where we are starting as an industry and provides a baseline to target the work we're doing and the impact it's having over time," Morrison says.

This kind of industry-level action about the gender gap is needed if institutional change is to be achieved. The conversations inspired by MassBio's letter are vital. "It's important to address subconscious biases that exist in the industry," says Magovcevic-Liebisch. She also says there needs to be an industry-wide effort to make women feel supported to take risks. "Women aren't taught to feel as comfortable as men in taking risks, so it's imperative for the industry to support them. People say we need more women in STEM, but I don't think that's the real issue. The issue is encouraging people to take risks and have the support they need to take these higher-level positions. If they don't feel supported, they drop off. The conversation needs to be changed to provide support and make women feel comfortable asking to move up." Conversation and support will go a long way, but likely more innovative, game-changing solutions are out there. Banard says it's time the industry brings its innate problem-solving talent to bear on this issue. 'In operations, when we have issues, the first thing we do is define the problem statement, form cross-functional teams, and look for root causes. If gender parity is considered a problem, why not use tried-and-true, problem-solving methods to fix it?"