Why Animal Health Is The Next Big Growth Area

By Cathy Yarbrough, Contributing Editor

Follow Me On Twitter @sciencematter

The animal health industry is on a growth trajectory, powered by the popularity of pet ownership and a global population hungry for meat and dairy products.

The many large and small companies that develop and manufacture drugs and vaccines for pets and livestock animals are expected to generate $33 billion in sales by 2020, after a record $24 billion in 2014, according to the consulting firm Vetnosis. Wall Street and the European and Asian markets are paying attention. The highly respected J.P. Morgan Annual Healthcare Conference has set aside time for presentations by CEOs of animal health companies. Jefferies and Bank of America Merrill Lynch each have begun sponsoring animal health summits to inform their investors about the sector. For investors based outside the U.S., the first European Animal Health Investment Forum was held in February 2016 in London.

At the 2016 J.P. Morgan conference, Juan Ramón Alaix, CEO and director of Zoetis, a spin-off of Pfizer, said the animal health industry is “evolving from being a small part of pharma companies with little interest from investors to an important and distinct part of the healthcare sector.” Zoetis’ $2.2 billion IPO in 2013 is often credited with focusing the financial community’s attention on the factors that make the animal health industry a promising short- and long-term investment opportunity.

One of those factors is global population growth, according to PwC’s August 2015 report, Animal Health Strategy Playbook for an Evolving Industry. The worldwide population, totaling 7.4 billion as of March 2016, is predicted to soar to 8.5 billion by 2030. Additionally, urbanization and the rise of the middle class in emerging economies will increase the consumption of meat and dairy products.

“To feed the world in 2030, animal protein production will have to increase by 30 percent from its current level,” says Fabian Kausche, global head of research and development at Merial, the animal health division of Sanofi. “Without effective disease prevention and health management strategies, we’ll lose a lot of meat and dairy animals due to disease,” Kausche added.

The top five animal health industry market leaders and their reported FY2015 revenues are: Zoetis, $4.8 billion; Merck Animal Health, $3.3 billion; Elanco, a division of Eli Lilly, $3.1 billion; Merial, €2.5 billion ($2.8 billion); and Bayer Animal Health, €1,490 million ($1.7 million).

"The average development time for an animal health product is three to seven years, not that much less than for human drugs and vaccines."

Fabian Kausche

Global head of R&D, Merial

The animal health industry has profited from the rise in pet ownership and increased spending on healthcare for pets. An estimated 65 percent of U.S. households have pets, and that percentage is expected to increase, said Kausche. According to a 2015 Harris Poll, 95 percent of U.S. dog and cat owners consider their pets as members of the family. “Companion animals over the years have moved from the barn to the garage to the living room to the bedroom to the bed,” said Steven Roy, president and CEO of VetDC, one of the numerous small companies in the animal health sector. VetDC evaluates experimental human cancer drugs to determine whether they would be safe and effective in the treatment of pets with cancer. VetDC’s leading cancer drug, acquired from Gilead Sciences, is under FDA review for the treatment of lymphoma in dogs.

Because pet dogs and cats are now living longer, they are at increased risk for developing cancer and other age-related disorders such as osteoarthritis, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and renal disease. Thus, age-related disorders provide niche markets for the animal health industry.

THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN BIG PHARMA AND ANIMAL HEALTH

The rise in pet ownership and the projected increase in the growing global population’s demand for meat and dairy products are not the only reasons that investors are paying more attention to the animal health industry. The R&D cost for a new animal health drug is about $50 million to $100 million compared to more than $1 billion for a human drug, Kausche said. In addition, veterinary drugs and vaccines have a long life. Because veterinary medicine is primarily a cash-based business, third-party payors play a minimal role in the animal health industry.

However, unlike the human biopharmaceutical industry, the animal health sector rarely has produced a blockbuster product. Merial’s Frontline flea and tick control product is the only pet medication that has generated annual sales of more than $1 billion, making it the first blockbuster drug for pets.

The most critical difference between Big Pharma and animal health companies is “how quickly we in animal health can translate an idea into a product,” said Catherine Knupp, EVP and president, research and development at Zoetis. Unlike biopharmaceutical drugs for humans, experimental veterinary medicines can be immediately evaluated in the intended species. Thus, early in the R&D process, animal health company researchers can determine a compound’s safety and effectiveness. “In animal health, we also can look at our ‘patients’ over a longer period of their life cycle,” said Knupp. “So we’re able to obtain more specific, relevant, and predictable results about a new drug.”

Unlike human biopharmaceutical companies, the major animal health companies develop drugs and vaccines not just for one species, but for multiple species — chickens, cattle, pigs, and sheep, as well as horses, cats, and dogs. Because these different species do not share the same physiology and disease susceptibilities, animal health R&D is more complex than biopharmaceutical R&D. “Dogs are not miniature humans, and dogs and cats do not always have the same health conditions,” said Knupp, who spent 18 years in R&D on human biopharmaceuticals before joining the Pfizer animal health division that led to Zoetis.

Like the R&D process, the regulatory requirements in animal health and biopharmaceuticals are “comparable in terms of complexity,” Kausche said. In the EU, a single regulatory agency, the European Medicine Agency, is responsible for animal health drugs and vaccines. The U.S. regulatory agencies for animal health therapies include the USDA, EPA, and the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine. While the USDA reviews applications for new animal vaccines and biologics that act through the immune system, the FDA has purview of small molecules and other animal health drugs. The EPA plays a role in the review of new compounds against fleas, ticks, and other parasites.

Despite these differences, animal health R&D is basically a smaller-scale model of human biopharmaceutical R&D and is just as demanding and rigorous. “The average development time for an animal health product is three to seven years, not that much less than for human drugs and vaccines,” Kausche said. The time frame for animal health drug R&D may become longer as a result of the industry’s increased focus on new compounds and technologies, such as complex mAbs (monoclonal antibodies).

Merial and Zoetis have developed first-of-their-kind mAbs animal health therapies. When it was introduced in 2009, Merial’s mAbs cancer vaccine for dogs with stage II and stage III oral melanoma was the first USDA-approved therapeutic vaccine for the treatment of cancer in either animals or humans. In 2015, the agency granted a conditional license to Zoetis for its novel mAbs therapeutic to help reduce the clinical signs associated with atopic dermatitis in dogs.

"In animal health, we also can look at our ‘patients’ over a longer period of their life cycle. So we’re able to obtain more specific, relevant, and predictable results about a new drug."

Catherine Knupp

EVP and president, R&D, Zoetis

THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN ZOETIS AND MERIAL

Zoetis is the only one of the top five animal health industry leaders that is not part of a Big Pharma company. “Because Zoetis is not tied to another company’s priorities, we are able to establish our own customer-driven priorities and can collaborate with anyone and everyone,” said Knupp. Zoetis collaborates with more than 100 academic labs and other companies because, “we don’t have all the answers and capabilities,” she said. One of the company’s research partners is Oakwood Labs in Ohio. Zoetis and Oakwood scientists are working together to design a sustained-release injectable pharmaceutical for both pets and livestock. By lengthening the time between treatments, extended-release formulations should reduce the number of injections required to treat the animal.

Unlike Zoetis, Merial is a division of a global biopharmaceutical company. The R&D groups of Merial and Sanofi work together, said Kausche. “We have access to each other’s pipelines, technologies, and scientists,” he said. Merial also has forged more than 50 external research collaborations with small research companies as well as academic labs. “We also collaborate with governments globally. For example, when an epidemic of foot-and-mouth disease erupts in a country, Merial collaborates with the local government to quickly deliver a vaccine against the specific viral strain affecting the local livestock,” said Kausche. Foot-and-mouth disease can be economically devastating. The U.K. outbreak in 2001 affected an estimated 10 billion animals and cost the country $15 billion.

The virus responsible for foot-and-mouth-disease cannot infect humans. However, many animal viruses and other microbes can be passed to humans. “Sixty percent of infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, passed from animals to humans,” said Knupp. Merial and Zoetis are among the animal health companies that stand ready to respond quickly to the possible emergence of a new zoonotic infection. “By having research centers around the world, we can strive to be the first to know and fast to market, helping to prevent diseases in animals that could be dangerous to people,” said Knupp.

ANIMAL HEALTH EMBRACES TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCES

Like their Big Pharma counterparts, the major animal health companies have turned to technology to improve the development as well as the application of their products. For example, Merial has designed a vaccine delivery method that “has the potential to transform poultry vaccination practices around the world,” said Jerome Baudon, global head of the company’s avian business. The vaccine is an effervescent tablet that is dissolved in drinking water, which is then sprayed over a flock of poultry or administered nasally or orally to individual chickens. Merial’s vaccine against the highly contagious Newcastle disease virus is the first application of the effervescent delivery technology

Genomics technology, which has significantly advanced human drug development, also has been embraced in the animal health industry, particularly in livestock breeding. Zoetis scientists designed the first U.S.-based genomic test for the six most common and costly diseases among Holstein cattle. The test results help farmers selectively breed herds with reduced risks of health problems. Similar genetic tests have been designed to improve the breeding of sheep and Angus cattle.

Animal health companies also have recognized the potential of digital technologies to improve their relationships with customers and promote the health of their respective “patient” populations. Since January 2016, Merial has collaborated with the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Center for the Development and Application of Internet of Things Technologies to identify possible ways that networked devices (aka Internet of Things) can advance animal healthcare and wellness.

Zoetis is participating in a 42-month U.K.-based project to develop visual imaging methods and digital technologies that will help farmers improve the health and wellness of pig herds and enhance production efficiency. The $3 million project was funded by Innovate U.K.’s Agri-Tech Catalyst Award. In addition, Zoetis opened a Centre for Digital Innovation in London in 2015. This year, the company and the U.K.’s University of Surrey announced the establishment of the Veterinary Health Innovation Engine (vHive), a novel multidisciplinary center at the university that will promote the development and adoption of digital technologies in animal health, including disease surveillance and early detection.

What’s next in the animal health sector? The industry’s demand drivers of pet ownership and protein consumption are highly unlikely to change. Corporate changes, however, are expected to continue to influence the industry.

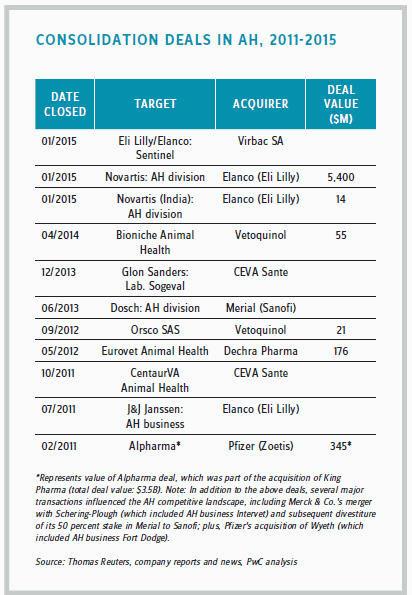

Because of Zoetis’ financial success and independence, business journalists often refer to the company as a possible takeover target. In December 2015, Sanofi and Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) announced a $12.5 billion asset swap in which Sanofi will hand over Merial to BI in exchange for the German company’s consumer health unit. If the deal is finalized, BI’s animal health division will become the second-largest animal health company. Such mergers are not unusual in the animal health sector. In 2015, Eli Lilly’s Elanco acquired Novartis’ animal health division.

The future of Bayer’s animal health division also is uncertain. In April 2016, Reuters reported that Bayer’s new CEO, Werner Baumann, is questioning whether the company’s animal health division is “well placed with us as best owner or can these businesses perhaps progress better in a different environment, with different access to resources?”