Partisanship Scuttles Bipartisan Reform Of SGR

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

March 15 — Something extraordinary has occurred in Washington: The three healthcare committees of jurisdiction quietly collaborated on a bipartisan basis to develop a replacement for the dysfunctional “Sustainable Growth Rate” (SGR) payment formula that dictates Medicare payments to physicians. Unfortunately, it was not to last. This substantial bipartisan achievement was soon scuttled and overtaken by the partisan bickering over the healthcare issue that has consumed the country for the past five years: implementation of Obamacare.

March 15 — Something extraordinary has occurred in Washington: The three healthcare committees of jurisdiction quietly collaborated on a bipartisan basis to develop a replacement for the dysfunctional “Sustainable Growth Rate” (SGR) payment formula that dictates Medicare payments to physicians. Unfortunately, it was not to last. This substantial bipartisan achievement was soon scuttled and overtaken by the partisan bickering over the healthcare issue that has consumed the country for the past five years: implementation of Obamacare.

The SGR has vexed policymakers for more than a decade. Enacted as part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, the SGR requires payment cuts to physicians and other practitioners when cumulative Medicare spending on those providers exceeds GDP per capita growth. The formula worked for a few years in the late 1990s when a growing economy fueled by the dot-com bubble allowed for modest pay increases that approximated physician practice cost increases.

But that bubble burst, and the more typical trajectories of healthcare costs outpacing the economy resumed. As a result, the SGR called for payment cuts. Congress allowed a 5 percent cut to occur in 2002 but has legislatively intervened more than a dozen times since then to override scheduled payment cuts. The “SGR fix” has become an annual ritual in Washington, creating a legislative vehicle that policymakers have often used to cut other providers or tack on other unrelated health items.

Congress funded the initial SGR fixes by steepening physician payment cuts in the “out years,” kicking the can to a future Congress. We are living in those out years now. Result: Physicians across America now confront a 23 percent cut for the care they provide Medicare beneficiaries. Cuts of that magnitude would have a cataclysmic impact on healthcare and make patient access for Medicare beneficiaries more akin to Medicaid.

Just as troubling, these constantly looming cuts have restrained physician practice investments in new technology and spurred thousands of physicians to exit independent practice entirely by becoming employees of hospitals. How can any business operate with a threat of possibly losing nearly a quarter of its revenue from its major customer base if Congress fails to enact a law?

Lower Score = Opportunity for Reform

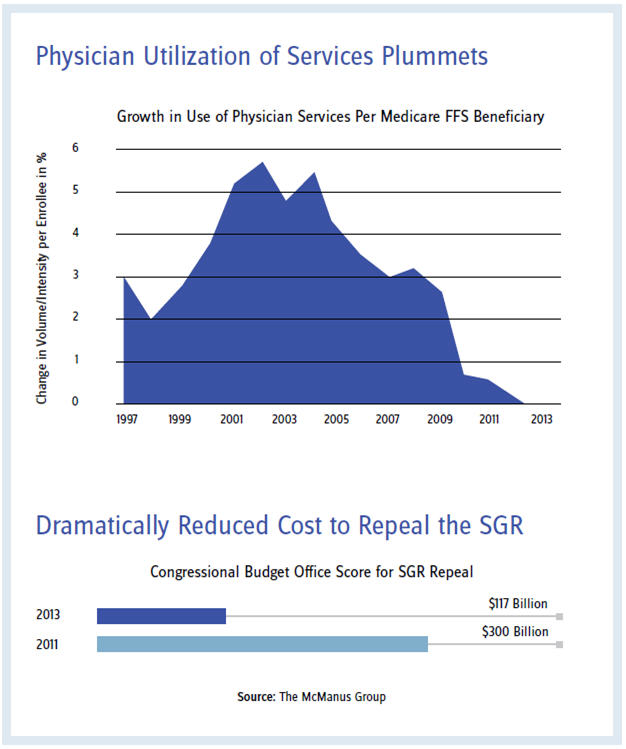

Congress and the physician community caught a break last year when the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) finally acknowledged that six years of steadily declining physician volume growth per capita constituted a trend (see chart on page 12). Policy makers were shocked when the CBO cut the cost of repealing SGR by 60 percent — dropping it from about $300 billion over 10 years to $117 billion.

That reduced score spurred Congressional action to develop a program that would replace the SGR, as policymakers did not want to simply write doctors a blank check or create a new formula that would come back to bite them a few years later as SGR had.

The Energy and Commerce Committee was first out of the box in July of 2013 with a bill developed by the bipartisan staff with substantial input by Rep. Burgess (R-TX) and the House Physician Caucus. The Senate Finance Committee and House Ways and Means Committee worked in bipartisan, bicameral collaboration throughout the autumn to develop legislation that not only repealed and replaced SGR but also consolidated the disparate incentive programs on quality reporting, electronic health records, and valuebased modifiers that were enacted over the past decade. Those bills were voted out of committee on a bipartisan basis in December.

After six more weeks of negotiation and hard work, the three committees introduced bicameral, bipartisan consensus legislation that would repeal and replace SGR. The bill encourages physician practices to strive to deliver higher quality and become more conscious of the resources physicians prescribe in all sectors of healthcare by eventually putting 9 percent of their payments at risk. Physicians will be judged on metrics that specialties develop based on how they compare to their peers. The bill encourages value over volume by enabling practices to develop alternative payment models that could include capitation and bundled payments.

Offsets: Still Fundamental Impediment

Of course, the fundamental impediment to enactment — how to finance the bill — had been mitigated by the lower CBO score but remained fundamentally unsolved. Interest groups assailed Congress, making the case that they should not be a focus of the savings. AARP threatened retribution on any member that voted for Medicare reforms that result in higher beneficiary costs. The American Hospital Association, nursing homes, pharmaceutical companies, and other sectors initiated all-out lobbying campaigns to convince Congress that they had paid enough for the Affordable Care Act and could not absorb additional cuts.

When robbing Peter to pay Paul, you’ll find few volunteers to play the role of Peter.

"The Republican leadership had selected the most controversial provision in Obamacare."

The House leadership’s clever way to finance the bill dissolved the bipartisan comity: Repeal Obamacare’s individual mandate to purchase health insurance. The CBO estimated this would save hundreds of billions of dollars because fewer individuals would be coerced into buying highly subsidized coverage. Republicans argued that the Obama administration had waived scores of provisions of Obamacare that helped businesses, insurance companies, hospitals, and others. Why not delay the provision most onerous to the individual — the mandate to purchase coverage?

The Republican leadership had selected the most controversial provision in Obamacare. It was the basis for the Supreme Court review of the law and the administration viewed it as critical to a functioning healthcare marketplace, arguing that it would deter adverse selection. But the Republicans felt that the administration would waive this provision in essence anyway by making so many hardship exceptions that it would be a mandate in name only. Why not capture the savings and solve the SGR at the same time? The bill passed with a dozen Democrats joining a unified Republican conference.

The Senate quickly announced that it would call up the SGR reform legislation with no offset whatsoever — the one approach the House could not accept. Newly installed Finance Chairman Wyden introduced new legislation without notifying his Republican counterpart and partisan acrimony deepened. A temporary patch now looks likely, and the sword of Damocles will continue to hang over physicians’ heads. Congressional paralysis continues…

Update on Part D Rule

In February’s issue, I reported on the controversial proposed rule CMS (Center of Medicare and Medicaid Services) issued that would have gutted patient access protections in Medicare Part D. The agency encountered withering push back from 371 organizations representing millions of patients, seniors, and multiple healthcare stakeholders, as well as bipartisan opposition from the finance committee. But it took the scheduling of a vote in the House of Representatives to strike the regulation that forced CMS to summarily withdraw the proposal the morning of the vote. An important victory for a program that is working!