Why Is The President Attacking The Successful Medicare Part D Program?

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

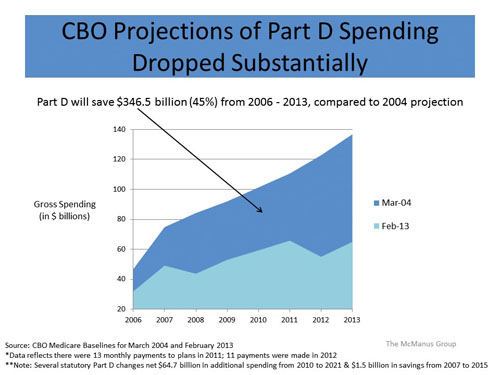

In February, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its new “baseline” projections for Medicare spending, and for the eighth time in nine years it reduced its projections for prescription drug spending under Medicare Part D. Indeed, the 2013 estimate for the next 10 years is 8.9% lower than last year’s estimate and a staggering 45% less than initial estimates for the cost of the program. Yet the Obama administration continues to advocate for the application of Medicaid rebates on low-income populations in Medicare Part D, which would slap the pharmaceutical industry with a more than $137 billion bill over 10 years for selling drugs to the program. What’s going on here? Why is the administration attacking a program that is producing tremendous results for our seniors and taxpayers alike?

In February, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its new “baseline” projections for Medicare spending, and for the eighth time in nine years it reduced its projections for prescription drug spending under Medicare Part D. Indeed, the 2013 estimate for the next 10 years is 8.9% lower than last year’s estimate and a staggering 45% less than initial estimates for the cost of the program. Yet the Obama administration continues to advocate for the application of Medicaid rebates on low-income populations in Medicare Part D, which would slap the pharmaceutical industry with a more than $137 billion bill over 10 years for selling drugs to the program. What’s going on here? Why is the administration attacking a program that is producing tremendous results for our seniors and taxpayers alike?

First, some background. In 2003, the Republican Congress enacted a market-based drug benefit that relied on competing prescription drug plans to deliver pharmaceuticals to Medicare beneficiaries. The concept was simple but revolutionary in health policy at the time — rather than establishing price controls and government formularies, trust seniors to choose the plans that suit them best and rely on the market to contain costs. Plans that were ineffective at negotiating with pharmaceutical companies and encouraging generic substitution would be priced out of the market and fail to attract seniors.

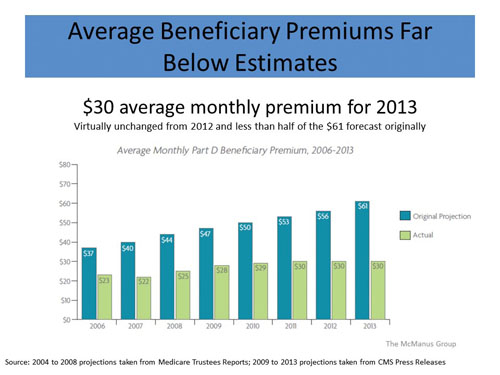

During congressional consideration of the bill, Republicans rejected an amendment that would have locked in prescription drug premiums at $35 a month for every plan — the then CBO estimate of the “average” prescription drug plan. That amendment would have destroyed the whole concept of the program by undermining any incentive of plans to aggressively contain costs in order to attract more beneficiaries. Mandated equality is antithetical to capitalism.

Thank goodness that amendment was defeated. When the program actually rolled out a few years later, the average monthly prescription drug premium was $23 or 40% cheaper than CBO’s estimate. Critics dismissed these low premiums as abject attempts to nefariously gain market share in order to hike premiums in subsequent years. However, premiums actually declined in the second year of the program. While healthcare costs have increased, Medicare prescription drug premiums have remained stable at $30 for the past three years. And generic utilization — a metric for efficiency of the program — has increased from 60% in 2006 to 80% in 2011, which is substantially higher than commercial plans.

A deficiency of the drug benefit was addressed when the Affordable Care Act (ACA) required brand-name companies to provide a 50% discount for drugs dispensed in the coverage gap, i.e. the “donut hole,” and also gradually eliminates this benefit gap over the next 10 years. It left the competitive market delivery of the benefits in place.

But less than a year after working with the President to enact health reform, the pharmaceutical industry was shocked that the President proposed applying Medicaid rebates to lowincome individuals in the Medicare program.

The Administration’s argument was that the pharmaceutical industry had received a “windfall” because dually eligible beneficiaries who formerly received their drug benefits through Medicaid were no longer paying Medicaid rebates to states. Medicaid rebates are nothing more than price controls and based on a three-pronged formula: 1) a minimum rebate of 23%, 2) best price rebate if a privately negotiated price discount exceeds the minimum rebate, 3) any price increase that exceeds inflation (measured by the consumer price index) since launch of the product. Medicaid rebates average about 45% for a typical brandname drug, but for some products they may be as high as 70% or more because of the penalty for price increases. The administration’s argument has several fundamental flaws:

- Medicaid is a notoriously poor payer and should not be the standard for appropriate pricing in Medicare. There’s a reason why the administration supported a provision in the ACA to increase reimbursements for primary care physicians in Medicaid to the Medicare level — very few physicians accept Medicaid patients because they lose money on those patients.

- Price controls inevitably accompany restrictions and shortages. The Veterans Administration, which administers a price control regime, covers fewer than 40% of the most commonly used drugs by seniors while the most popular Medicare prescription drug plans cover about 84% of those drugs. Medicaid is similarly restrictive; the Kaiser Family Foundation reports that 16 states limit the number of prescriptions a beneficiary may fill, which can be devastating for Medicaid beneficiaries.

- The Medicaid rebate would be applied to not just the 6 million dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries, but another 5 million low-income beneficiaries — a population that never had Medicaid coverage or its price control scheme.

- Numerous economic studies by government actuaries and leading academics have documented that pharmaceutical price controls will result in pricing distortions that will hike prices to employer plans, veterans, and nonlow income Medicare beneficiaries. Not everybody can get prices better than average.

So why is the administration pushing such a policy when the pharmaceutical industry already contributed more than $100 billion to healthcare reform? Answer: Expanded Medicaid rebates will substantially restrict pricing flexibility for brand-name pharmaceutical companies. Under the Administration’s proposal, any cumulative price increase that exceeds the CPI since launch will be recaptured as a rebate for about half of the drug spend in the Medicare program, in which free market pricing now applies. It wants control over pharmaceutical pricing.

If the administration gets its way, there are only two possible outcomes: 1) substantial cuts to research and development, particularly for the more risky endeavors; and 2) job cuts to an industry that has already laid off 200,000 workers over the past several years. The Battelle Institute estimates that an impact of $10B to $20B a year on the industry, as the administration proposes, would result in 130,000 to 260,000 lost jobs in the high-wage pharmaceutical sector and the industries it supports.

I am not aware of any government program that has come in 45% below budget, is vastly popular with its customers, and yet is being targeted for a fundamental overhaul. Congress should reject such a proposal.

John McManus is president and founder of The McManus Group, a consulting firm specializing in strategic policy and political counsel and advocacy for healthcare clients with issues before Congress and the administration. Prior to founding his firm, McManus served Chairman Bill Thomas as the staff director of the Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, where he led the policy development, negotiations, and drafting of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. Before working for Chairman Thomas, McManus worked for Eli Lilly & Company as a senior associate and for the Maryland House of Delegates as a research analyst. He earned his Master of Public Policy from Duke University and Bachelor of Arts from Washington and Lee University.