Biomarkets: Looking For The Hole In The Donut

By Allan L. Shaw, a five-time public company CFO (e.g., Serono & Syndax) and has served on five public boards, which included the chairing of two audit and two compensation committees.

The capital market IPO drought of 2008 to 2012 seems like a distant memory — funny how more than 120 IPOs can make us forget such a painful period. Furthermore, the strength of the biopharma sector has been buoyed by the stellar performance of large cap stocks driven by exciting product launches and impressive clinical data. Not since 2000 has the industry experienced such relevance and broadened interest, as evidenced by the investor cash inflows. Given this incredible run, the market has become increasingly optimistic, at times even displaying a cavalier disregard for the risks and execution challenges implicit within the biopharma industry. While such success has left most industry stakeholders pinching themselves, for many it has also called into question the valuation levels we see today. Is this run-up in sector valuations an indication that we are in the midst of a bubble?

The capital market IPO drought of 2008 to 2012 seems like a distant memory — funny how more than 120 IPOs can make us forget such a painful period. Furthermore, the strength of the biopharma sector has been buoyed by the stellar performance of large cap stocks driven by exciting product launches and impressive clinical data. Not since 2000 has the industry experienced such relevance and broadened interest, as evidenced by the investor cash inflows. Given this incredible run, the market has become increasingly optimistic, at times even displaying a cavalier disregard for the risks and execution challenges implicit within the biopharma industry. While such success has left most industry stakeholders pinching themselves, for many it has also called into question the valuation levels we see today. Is this run-up in sector valuations an indication that we are in the midst of a bubble?

Remember, though, the market is still exhibiting elements of rational behavior. For example, during the last two years, nearly a third of the biopharma IPOs have traded below their initial offering price.

Nevertheless, there is certainly reason for bubble conversations to be taking place. The big question is: How did we get here, and where are we going? This euphoric period for biopharmaceuticals, notwithstanding high valuations by all conventional metrics, has been driven by a confluence of fundamental dynamics such as:

- low interest rates (desire for beta [i.e., the tendency of a security’s returns to respond to swings in the market])

- lack of risk-capital alternatives (e.g., funds used for high-risk, high-reward investments such as emerging markets, precious metals, or emerging biotechnology stocks)

- generalists’ (vs. industry specialists) capital allocation to biopharmaceuticals

- FDA lowering the bar (i.e., record new drug approvals, particularly with biologics)

- capital/clinical efficiency and proliferation of targeted therapies, orphan diseases, new modalities and technologies (e.g., gene therapies), and new drug categories (immuno-oncology) reflecting better scientific understanding of the mechanism of indicadiseases coupled with our evolving knowledge and application of genomics coupled with companion diagnostics

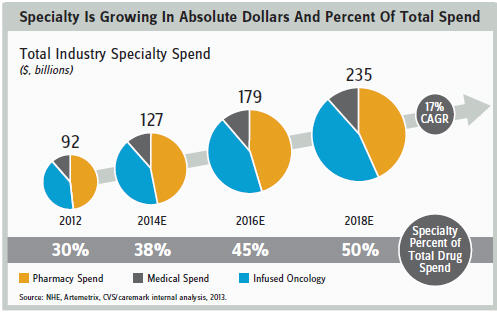

- increase in specialty-drug spending related to new and exciting drugs launches (e.g., Solvadi, Keytruda, Yervoy/Opdivo, Tecfidera)

- the shift in Big Pharma resource allocation has created a proliferation of M&A and partnering deals, which indicate a de-emphasis on internal research and increased emphasis on external collaborations

- the emergence of a supply/demand imbalance for new companies (The capital markets’ prior drought adversely impacted the VC community and its capacity to create new companies. This lack of startups or eco-system deficiency has given rise to demand-driven premiums for innovative drugs and technology platforms.)

These market drivers reflect an industry that is maturing and is no longer considered a backwater asset class for investors. Just look at the proportional growth of biologics prescriptions relative to total scripts, clinical success/ efficiency (e.g., three-fold increase in productivity of blockbuster agents since 20101), and the dramatic rise in new drug approvals (hitting an 18-year high in 2014, with biologics representing 35 percent of new drugs approved2).

These factors all have contributed to the significant increase in capital allocation as evidenced by the huge fund inflows to biologics.

BIOPHARMA INDUSTRY RISKS

All of these changes have led investors to conclude that an industrial paradigm shift is afoot, which, in turn, has caused the market to rationalize valuations and ignore the inherent industry and macroeconomic risks, such as:

- pricing headwinds and cost-containment initiatives

- clinical attrition

- regulatory hurdles

- safety risks

- competitive landscape

- reimbursement challenges

- rise of biosimilars

- intellectual property challenges

- unfunded business plans (Man developmental-stage companies generally have enough financial resources to only achieve valuation inflection points — hopefully — that correlate to clinical/developmental activities, reflecting their dependency on evergreen access to capital markets.)

- execution risk

- interest-rate hikes.

The biopharmaceutical sector is the epitome of risk (e.g., scientific, clinical, regulatory, commercial). These industrial jeopardies are pervasive and represent significant operational and strategic challenges that may not be fully appreciated nor adequately represented in company valuations. This begs the question, “What happens when the capital markets reacquaint themselves with risk?” Despite the significant advancements in efficiency and effectiveness previously referenced, only a relatively low percentage of clinical-stage products under development will be successfully commercialized. This leads us to question whether or not those inevitable outcomes are reflected in the capital markets (i.e., can everyone be a winner?). This point is particularly acute when considering the emerging innovative medicines/technologies that are in development (e.g. CAR-T [chimeric antigen receptors T-cells], gene and immunotherapies) because they take longer to develop/commercialize and their limited patient experience/history implicitly means higher risks. A good example is RNAi (ribonucleic acid interference). RNAi initially suffered because development took longer than anticipated, but now it is starting to show immense potential more than a decade after its debut. This underscores the point that good science coupled with time and money can overcome obstacles, but success can require significantly more resources, perseverance, and luck than originally anticipated. Clearly, the business of drug development is not for the faint of heart.

PRICE/COST CONTAINMENT ISSUES

While the scientific risks are daunting, the commercial risks may prove to be the biggest long-term challenge. Consider the global cost-containment initiatives aimed at tethering unsustainable healthcare spending. These initiatives have created concerns that the healthcare system will not be able to support widespread access to beneficial medicines. Although drugs represent a relatively small proportion of total healthcare costs, they are still destined to come down in price as outcomes-based/ capitated pricing (dare I say, “risk-sharing” or “value-based pricing”?) that emphasizes cost-effectiveness becomes the norm.

Europe (e.g., U.K. and Germany) offers insights into cost-containment models that have effectively created downward pricing pressures on drug manufacturers. The U.K.’s NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) could provide foresight of things to come. Currently, the price of a drug in the U.S. is often twice or possibly even five times that of the same drug in Europe. This begs the question: “How long will the U.S. continue to subsidize global medicine?”

Unfortunately, only through hindsight will we be able to answer any of the questions we’ve posed here regarding the industry’s valuations/expectations and related risks. I am not sure we could ever agree where we go from here, but nevertheless, I would suggest the following:

- Do not try to time the market; grab the money when you can.

- Go public when you can; companies have much better success with capital market access once they have listed their securities.

- Continue allocating resources in the same manner you did with your last $100. Organizations are generally more effective with capital deployment when they have less as opposed to more.

- Make sure your business plans are funded to the next value inflection point along with some additional reserves in case things do not evolve as planned.

- Focus on keeping your promises to maintain creditability with investors and market access.

- Maintain investor confidence; access to the capital markets is a privilege and not an entitlement. Embrace the fundamental principle of under promising and over delivering.

- Apply the lessons learned from the last capital market drought. Did you learn any?

Moving forward, we can be certain there will be more big winners, but it is important to understand there will also be losers. Perhaps the capital markets are behaving rationally on a macro level and will simply be reallocated among winners and losers with outsized gains/losses — rewarding companies that are executing and penalizing those that are not. In a rising tide, all boats are lifted; it is when things get tough that the true mettle of management teams is tested. As such, pick your management teams wisely. If history is any indication of the future, trips to the capital markets will not continue to be as easy as visiting your ATM machine — though only time will tell.

(1) Gorkin L, Gruzglin G. Improving productivity in innovative drug development warrants a return to value-based pricing. In U. Staginnus and O. Ethgen (Eds.), The Future of Health Economics. Gower, in press, 2015.

(2) Forbes 1/02/2015