Biopharma IPR Trends

By Michael Siekman and Oona Johnstone, Ph.D., Wolf Greenfield

It has been almost five years since post-grant proceedings, including inter partes reviews (IPR), were implemented under the America Invents Act as an alternative to patent litigation for challenging granted patents. Taking place before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, these proceedings quickly gained the reputation of being patent “death squads,” because they resulted in surprisingly high rates of patent cancellation and therefore became a complement to most patent litigations.

It has been almost five years since post-grant proceedings, including inter partes reviews (IPR), were implemented under the America Invents Act as an alternative to patent litigation for challenging granted patents. Taking place before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, these proceedings quickly gained the reputation of being patent “death squads,” because they resulted in surprisingly high rates of patent cancellation and therefore became a complement to most patent litigations.

While biopharma patents initially represented a small percentage of postgrant proceedings, that percentage has been increasing. In particular, generic and biosimilar manufacturers are taking advantage of these proceedings, not just as a complement to litigation, but also to clear patents covering brand-name drugs and biologics before litigation occurs.

POST-GRANT STATISTICS ACROSS INDUSTRIES

Biopharma represented 13 percent of post-grant petitions filed in 2016, up from 9 percent in 2015. There are likely several reasons for this relatively low percentage. IPRs are often filed concurrently with litigation, so the filing rates tend to be highest in the more litigious technology areas, such as electronics. Also, the timeline for bringing a drug or biologic to market is lengthy, so post-grant proceedings in biopharma tend to be part of a long-term business strategy in which there may not be the same immediate time pressure to file quickly that exists in other industries. Finally, IPRs are limited to prior-art grounds, and only certain ones at that. A separate category of post-grant proceedings called post-grant review (PGR) — which allows for challenges on all patentability grounds, including patent-eligible subject matter and sufficiency of description, which tend to be highly applicable to biopharma inventions — is just starting to become available. Accordingly, we can expect to see a significant increase in biopharma post-grant proceedings in the coming years.

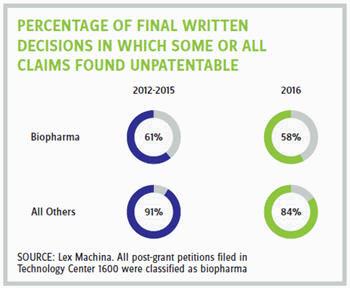

In general, post-grant proceedings have been highly successful for petitioners. However, the statistics have been less favorable for petitioners in biopharma than in other technologies. This trend can be seen in part at the institution stage, when the PTAB decides whether to initiate a post-grant trial. For biopharma petitions that reach this stage, the institution rate is approximately 63 percent, compared with 71 percent for all other technologies combined. Significantly, this trend is even more apparent at the final written decision stage. In biopharma, from 2012 to 2015, for petitions that reached this final stage, approximately 61 percent resulted in at least one claim being found unpatentable, with the percentage dropping slightly to 58 percent in 2016. By comparison, in all other technologies combined, from 2012 to 2015, a striking 91 percent of petitions that reached this final stage resulted in at least one claim being found unpatentable. While this percentage dropped slightly in 2016 to 84 percent, it is still significantly higher than in biopharma.

Accordingly, biopharma patent owners can take some solace in the fact that their patents appear to be more readily able to withstand IPR challenge than patents in other technology areas. This is primarily due to the recognized unpredictability in biopharma. Obviousness analysis plays a critical role in biopharma post-grant proceedings, and patent owners have been successful in using unpredictability to their advantage by arguing lack of reasonable expectation of success in achieving biopharma inventions.

ADVANTAGES OF IPR FOR GENERICS AND BIOSIMILARS

ADVANTAGES OF IPR FOR GENERICS AND BIOSIMILARS

Post-grant proceedings, such as IPRs, present multiple advantages over litigation for parties wishing to challenge a biopharma patent, such as generic and biosimilar manufacturers. In particular, the proceedings are decided by a panel of Administrative Patent Judges (APJs) who are highly technically trained and more comfortable finding patents unpatentable, as opposed to a district court judge and jury. This can be especially relevant in complex technical areas, such as biopharma, where decisions on patentability frequently rest on obviousness analysis (i.e., analysis of whether the claimed invention would have been obvious to one of ordinary skill in the art) including interpretation of secondary considerations where APJs have proven skeptical of patentees’ arguments. Relative to litigation, petitioners in post-grant proceedings also benefit from a broader standard for claim construction (“broadest reasonable interpretation”), a lower standard of proof (preponderance of the evidence instead of clear and convincing evidence), and a related lack of presumption of patent validity.

Post-grant proceedings are also generally considerably faster and less expensive than litigation and can be filed by essentially any entity (other than the patent owner). Additionally, courts frequently stay concurrent litigation pending the outcome of a post-grant proceeding, since the result of the proceeding can simplify, or even eliminate, the issues needing to be litigated.

INSIGHTS FROM EARLY GENERIC IPR CHALLENGES

Multiple IPRs filed by generic manufacturers have now reached final written decisions. While the first series of decisions favored the patent owners, the results have since shifted somewhat to favor the petitioners, indicating that in some instances, generic manufacturers are succeeding in using this approach to eliminate blocking patents.

Noven Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Novartis AG and LTS Lohmann Therapie-Systeme AG

These IPRs represent an example where generic manufacturers successfully used IPRs to cancel claims that had previously been found to be patentable in litigation. Noven and Mylan challenged two patents covering the Exelon patch, marketed by Novartis for treatment of dementia. Both patents had been litigated at least once in district court and on appeal at the federal circuit, with each court upholding the validity of the patents. Significantly, when Noven and Mylan challenged the same patents in an IPR, the PTAB reached the opposite conclusion, finding all the challenged claims unpatentable and noting, in part, the different standard of proof in an IPR relative to litigation.

Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Amneal Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Yeda Research and Development Co. Ltd.

These IPRs represent an example where generic manufacturers successfully used IPRs to clear blocking follow-on patents. Mylan and Amneal challenged three patents covering “3-times-a-week COPAXONE 40 mg/ ml,” marketed by Teva. The challenged claims were directed to methods of treating multiple sclerosis by administering three 40 mg injections of Copaxone over seven days. The PTAB determined the claimed dose regimen was obvious over prior art that disclosed administering 40 mg doses of Copaxone every other day. While the PTAB acknowledged a presumption of a nexus between the drug’s commercial success and the claimed dose regimen, it found that the petitioner overcame this presumption by showing that, rather than being attributed to superior properties of the claimed invention, commercial success was largely a result of brand recognition combined with aggressive marketing and substantial price discounts aimed at outcompeting generics of the original version of Copaxone.

EXAMPLES OF EARLY BIOSIMILAR IPR CHALLENGES

The majority of IPR challenges by biosimilar developers have not yet reached the final written decision stage; however, early trends are evident from institution data. For example, at least 14 petitions have been filed by multiple biosimilar developers challenging follow-on patents covering the blockbuster therapeutic monoclonal antibody Humira. Consistent with general trends in biopharma, out of the petitions that have reached the institution stage, approximately 60 percent were instituted. Interestingly, all of the petitions that were not instituted were directed to biologic formulations patents, which have proven to be more resistant to IPR challenge than small molecule formulation patents thus far.

In the first biosimilar IPR to reach a final written decision, biosimilar developer Momenta Pharmaceuticals, Inc. challenged a follow-on formulation patent covering Orencia, marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Here, the PTAB found that the petitioner had not demonstrated by a preponderance of the evidence that the challenged claims were obvious. In particular, the PTAB was not convinced that there was a reasonable expectation of success in developing the claimed stable liquid formulation of this biologic, upholding all of the challenged claims for the patent owner.

TAKEAWAYS

Biopharma post-grant proceedings, including both IPRs and PGRs, are increasing. Post-grant proceedings offer multiple advantages over litigation for petitioners to clear blocking patents. However, the timing of challenging a patent is an important strategic consideration, since clearing a patent can also open the market to other competitors. Biopharma petitioners face a greater challenge relative to petitioners in other areas of technology, due to lower institution rates and lower percentages of final written decisions that result in cancellation of at least one claim. Nevertheless, biopharma petitioners, including generic and biosimilar manufacturers, are successfully using these proceedings to achieve their business goals — for example, to remove blocking patents to allow for market entry, or to get a second chance at cancelling claims that had been upheld in litigation.

Michael Siekman is a shareholder and Oona Johnstone, Ph.D. is an associate in the Biotechnology and Post-Grant Proceedings Practices at intellectual property law firm Wolf Greenfield in Boston.