Biosimilar mAbs: Expanding The Global Biosimilar Market

By Cliff Mintz, - Contributing Editor

After almost a decade of debate, there is now a generally agreed upon definition for biosimilar molecules: a biological medicinal product that contains a version of the active substance of an already authorized original biological medicinal product (reference product) that demonstrates similarity to the reference product in terms of quality characteristics, biological activity, safety, and efficacy based on a comprehensive comparability exercise.

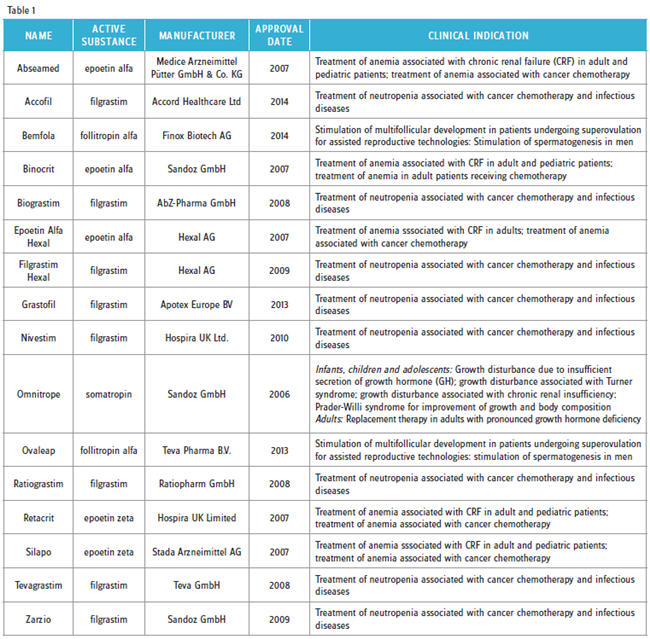

Since 2006, 16 biosimilar products have received marketing authorization in Europe (Table 1). Of these so-called “first-generation biosimilars,” eight were different biosimilar versions of filgrastim (G-CSF), and five were biosimilar copies of different erythropoietin (EPO) molecules. Typically, these products are sold at prices ranging from 25 to 40 percent less that the corresponding branded molecules.

Since 2006, 16 biosimilar products have received marketing authorization in Europe (Table 1). Of these so-called “first-generation biosimilars,” eight were different biosimilar versions of filgrastim (G-CSF), and five were biosimilar copies of different erythropoietin (EPO) molecules. Typically, these products are sold at prices ranging from 25 to 40 percent less that the corresponding branded molecules.

Yet, despite discounted prices, uptake of biosimilars has been slower than anticipated, and successfully commercializing them has been challenging. One of the reasons for this, according to Roman Ivanov, VP of R&D for Biocad, a Russia-based biosimilar development company, is that “years ago the medical community was not ready for non-originator products. Many doctors were overwhelmed by the complexity of biologics, did not really understand what biosimilars were, and were reluctant to prescribe them.” Further, Magdalena Leszczyniecka, president and CEO of Cambridge, MA-based STC Biologics, a biotechnology company that specializes in biosimilar analytics and process development, suggested that regulatory confusion (mainly in the U.S.), coupled with quality and safety questions promulgated by innovator companies, has historically hindered first-generation biosimilar acceptance and uptake.

However, first-generation biosimilars like G-CSF and EPO have continued to garner increasing market share since 2010. Carol Lynch, global head of biopharmaceuticals & oncology injectables at Sandoz, pointed out that in 2013 its biosimilar G-CSF (Zarzio) outperformed its reference standard (Amgen’s Neupogen), and it is currently the top prescribed daily G-CSF in Europe. Likewise, biosimilar EPO now accounts for ~60 percent of EPO prescriptions in Germany. Nevertheless, Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, chairperson and managing director of Bangalore, India-based Biocon, believes that lessons learned from early commercialization experiences with first-generation products and much-improved product awareness will allow the next generation of biosimilars to more easily penetrate and quickly garner significant market share.

BIOSIMILAR MONOCLONAL ANTIBODIES: THE NEXT GENERATION

In 2013, global sales for eight branded monoclonal antibody (mAb) products that are used to treat a variety of chronic immunoinflammatory diseases and oncology indications was approximately $55 billion. Over the next five years, all of them will lose patent protection in Europe, and seven will no longer be patent-protected in the U.S.. Moreover, in May 2012, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) created a marketing authorization framework for mAbs and related products. These factors coupled with: 1) rising global biologics prices, 2) costsaving strategies implemented by national healthcare agencies, hospitals, and third-party payers, and 3) clearly defined regulatory pathways for approval of biosimilars have induced a number of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies to create biosimilar versions of several of the top-selling branded mAbs.

To date, biosimilar versions of Enbrel, Remicade, Rituxan, Humira, Herceptin, Avastin, and Lucentis are in early- to late-stage clinical testing in Europe and the U.S. The most advanced of these is SB4, a biosimilar version of Enbrel and Inflectra, a Remicade biosimilar. In 2014, the EMA agreed to review a market authorization application for SB4, and a biologics licensbiosimiing application (BLA) for Inflectra (infliximab) was filed with the FDA in 2014. Additionally, several biosimilar mAbs — Etanar (etanercept), Reditux (rituximab), Kikuzubam (rituximab), BCD-020 (rituximab), Exemptia (adalimumab), Herzuma (trastuzumab), and CanMab (trastuzumab) — are already being sold in various emerging markets.

Finally, in 2013, Inflectra and Remsima (infliximab) became the first biosimilar mAbs to receive marketing authorization in Europe. The EU marketing authorization for these products is considered a pivotal event in the commercialization of biosimilar mAbs because, prior to their approval, it was not clear whether or not biosimilar versions of mAbs could withstand the scrutiny of the comparability exercise given the molecular complexity of mAbs (as compared with simpler proteins like G-CSF and EPO). Also, both infliximab biosimilars have been approved in Canada, Korea, and Japan.

REMAINING ISSUES

There are several contentious issues that must be resolved before biosimilars can reach their full commercial potential. The first of these is indication extrapolation, a process by which a biosimilar is approved for all clinical indications held by a branded reference product with clinical data (generated during the comparability exercise) for only a subset of indications.

Biocon’s Mazumdar-Shaw offered, “Indication extrapolation reduces the cost of clinical development and allows for larger discounts that directly benefit patients and healthcare providers.” Sandoz’s Lynch and STC Biologic’s Leszczyniecka emphasized that indication extrapolation for biosimilars is essential for greater patient access and also ensures that biosimilars can compete with branded molecules. Biocad’s Ivanov was even more sanguine about indication extrapolation. “It is absolutely critical for commercial success because it substantially reduces development costs.” He added, “Without it, there is no sense in developing biosimilars at all.” However, he cautioned that indication extrapolation may not be appropriate when originator molecules are approved for divergent therapeutic indications diseases where the mechanism of action may be different, e.g., autoimmune diseases vs. oncology.

Historically, the EMA has allowed indication extrapolation for all biosimilars that have received marketing authorization. This was the case for Inflectra and Remsima, which received market authorization in Europe for all six clinical indications associated with the originator product Remicade. In contrast, Health Canada approved Inflectra and Remsima for only four of six indications, citing minor structural differences with the reference product that might affect therapeutic efficacy for the remaining two indications. “Analytical comparability data suggested that the mechanisms of action [efficacy] may be different for the remaining two indications,” said Leszczyniecka. Also, she cautioned, “It is likely that the FDA will impose the same level of scrutiny for biosimilar mAbs as Health Canada, given the FDA’s emphasis on the analytical portion of the comparability exercise.”

Another hotly debated topic is interchangeability/ substitution, the ability of two products to be exchanged or substituted at the pharmacy level (without consulting the prescriber) without any risks or significant adverse effects on a patient’s health. From a regulatory standpoint, interchangeability/substitution is a possibility in Europe, the U.S., and other markets. Not surprisingly, this practice is opposed by innovator companies and embraced by biosimilar manufacturers. While interchangeability/ substitution has not been granted to previously approved biosimilars, Lynch, Ivanov, and Mazumdar-Shaw all believe that it will eventually become a reality in most markets. However, both Lynch and Mazumdar–Shaw were quick to point out that its importance will vary with individual products. “For retail-dispensed chronic-care products like those used to treat autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, interchangeability/ substitution will be important. It will be less critical for oncology biosimilars which are usually dispensed in a hospital or clinical settings,” said Lynch.

Finally, in recent years, the naming/ classification system used for biosimlars has come under attack by innovator companies. At issue is whether biosimilars should be given the same International Nonproprietary Name (INN), or generic names, as innovator products. Brandname drugmakers want biosimilars to have unique INNs to distinguish biosimilars from their products, citing patient safety and possible problems with adverse event reporting. Sandoz’s Lynch emphatically offered, “The current system has worked well for biosimilars for over a decade, and there is no need to introduce any changes.” Similarly, Biocon’s Mazumdar-Shaw agreed with Lynch and warned, “Any changes to the current INN system for naming biosimilars will introduce unfair bias and unfair marketing advantages to innovator companies.” Nevertheless, biosimilar naming and INN designation remains a hotly contested topic.

WHAT NEEDS TO BE DONE TO MOVE FORWARD

There are several issues that must be addressed to ensure the next generation of biosimilars is successfully commercialized. First, physician/healthcare provider education and engagement are of paramount importance. “Engaging the medical community via key opinion leaders will be vital to validate the science used to develop biosimilars and to ensure physicians that biosimilar quality, safety, and efficacy are similar to their branded counterparts,” said Ivanov. Likewise, Sandoz’s Lynch said, “We need to educate physicians to get them more comfortable with the concept of indication extrapolation, which will be essential to support a sustainable business model for biosimilar mAbs.” Moreover, STC Biologics’ Leszczyniecka emphasized that educating and engaging other stakeholders, especially payers, pharmacy benefits management companies, and specialty pharma firms, will be critical for appropriate formulary placement and successful commercialization of biosimilars.

Second, Mazumdar-Shaw indicated that “There is much misinformation being spread about biosimilar ‘unknowns’ that is hurting biosimilar credibility among prescribers.” And this will likely continue as brand companies seek to protect multibillion-dollar drug franchises. In support of this, Amgen successfully sued the Norwegian government to prevent government-mandated automatic substitution of Neupogen with biosimilar versions of G-CSF. However, Mazumdar-Shaw opined that “Health economics will ultimately take precedent over fear-mongering, and over time biosimilar safety/ efficacy data will speak for itself.”

Finally, both Lynch and Leszczyniecka agreed that the commercialization strategy for the biosimilar mAbs will more closely resemble that for branded molecules as compared with the more traditional generic drug approach used for first-generation biosimilar commercial launches. Further, Lynch said, “From a commercialization perspective, one of the key things that Sandoz has learned over the last decade or so is that there is no one-size- fits-all solution for biosimilars.” She added, “In terms of Sandoz’s commercialization strategy, product launches will be tailored for specific market dynamics and based on prescribing habits/reimbursement strategies for individual molecules.”

Despite rising biologics prices and skyrocketing healthcare costs for the past decade, the global biosimilar market is still in its infancy. And, while some missteps were made commercializing first-generation biosimilars, biosimilar manufacturers are still learning as the global market continues to evolve. Therefore, today’s biosimilar mAbs are likely to fare much better both commercially and economically than their predecessors.