Biotech Bounces Back: A Tale Of Two Companies

By Gail Dutton, Contributing Writer

Follow Me On Twitter @GailLdutton

Double down, forge a new direction, or throw in the towel for your current project. Those are the options for surviving setbacks. Which approach you take may not matter without a clear and unemotional understanding of your company and its science.

Here’s a look at how two biotech companies faced their challenges and are bouncing back.

18 YEARS OF BOUNCING BACK

Oncolytics Biotech has been developing Reolysin as a cancer therapy for 18 years, based on the oncolytic properties of the reovirus. When this single-product company faced delays, it doubled down, going deeper into the science to learn more about its lead compound’s mechanism of action.

As Brad Thompson, Ph.D., CEO of Oncolytics, points out, (editor’s note: Dr. Thompson stepped down while this article was in production. Dr. Matt Coffey has been appointed interim president and CEO while the company conducts a search for Dr. Thompson’s replacement.) developing first-in-class therapies takes longer than more established approaches because of the combination of unknown or lesser-known mechanisms of action and new manufacturing methods. “The industry’s first cancer antibody took about 20 years to be commercialized,” he points out. By that timeline, Oncolytics is right on schedule.

Phase 2 trials began for Reolysin in 2001 in Canada and the following year in the United States. “If we had pushed ahead into Phase 3 trials immediately after completing Phase 2, the trials would have failed because we didn’t understand the mechanism of action then,” Thompson says. Delaying Phase 3 trials gave his team time to learn that this oncolytic virus has a dual mode of action, working as a cytotoxic agent to reduce the tumor burden while also stimulating the immune system.

Researchers also learned that the therapy has a significant gender bias, tripling therapeutic improvements in women with colorectal cancer. It also appears effective in treating metastatic disease. “Most studies don’t consider those areas,” Thompson says. Focusing on the underlying biologics allowed genomics to mature, so researchers may predict clinical responses for specific patients.

In its early days, Reolysin was directly injected into prostate tumors during Phase 2 trials. “The study results looked great, but none of the patients were willing to return for a second treatment,” Thompson recalls. Therefore, intravenous delivery was considered. “The FDA said ‘no way,’ so we went to the U.K. to conduct trials to define dosage and learn where the drug actually went in the body.” (It clears preferentially in the liver and crosses the blood-brain barrier.) With that knowledge, “we can conduct trials for pediatric brain cancers in the U.S.” Reaching that point took about seven years.

Trial design also affected outcome. “In a double-blind study in the U.S., we found patients dropped off the test arm because of low-grade fevers, which prevented the study from progressing,” Thompson recalls. Patient dropout wasn’t an issue, however, for the 13 open-label studies of head and neck cancers conducted in 13 other countries.

![]()

"We were almost out of business at one point. Investors get weary."

Brad Thompson, Ph.D.

Former CEO of Oncolytics

Additional delays were caused by the desire to learn which drugs, administered with Reolysin, supported viral replication and which prevented replication. Without viral replication, the therapy couldn’t work. Testing every known chemotherapeutic agent — including checkpoint inhibitors and other emerging therapies — cost $100,000 per patient and involved 500 patients. “Completing those investigations took about seven years,” he says.

Afterward, Reolysin was granted orphan drug status in the U.S. in 2015 for pancreatic, gastric, ovarian, primary, peritoneal, and fallopian tube cancer, and malignant gliomas. It has orphan drug status in Europe for ovarian and pancreatic cancer. Phase 3 trials are expected to launch in the U.S. in 2017 for nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and metastatic colon cancer.

WHY DOUBLE DOWN?

“We stayed with this drug because it worked,” Thompson emphasizes. “Our first radiation therapy had a 100 percent response rate in tumors. Patient 2 of 1,100 still visits me.” Without this treatment, that patient was expected to die 15 years ago. “That’s why you stick with a product. Patients are alive because of our clinical studies.”

Belief in a product or an approach is a powerful thing. “As CEOs, we convince investors to provide millions of dollars based on a concept. People invest in your company because you believe your approach will work. Over time, that conviction is converted into a belief based on data.”

INVESTORS NEED AN ENDPOINT

Nonetheless, investors expect an endpoint. Stock prices for Oncolytics have fluctuated from a high of $20 (October 2000) to 30 cents Canadian (October 2016) on the Toronto Stock Exchange. Still, Oncolytics raised $19 million Canadian in 2015 and ended the year with $26.1 million in cash and cash equivalents — enough to support upcoming studies.

“We were almost out of business at one point,” Thompson admits. “Investors get weary. That’s an important factor to consider in conducting added research. Nobody believed it would take us this long, but they don’t fault us for answering the questions we answered.”

He says many biotechs have survived similar situations and cites Amgen as one example. “Amgen’s management believed in what the company was doing. They plugged away, and one morning it had become one of the largest, most successful biotech companies in the world.”

For Oncolytics, once Phase 3 studies begin, an endpoint will be within sight. Assuming the multiple myeloma study is a success, the company could file for marketing approval in about two years.

The decision to remain a single-product company had no effect on fundraising, Thompson says. “Half the fund managers are obsessive about sticking to what you know. They mitigate risk by buying multiple companies, so those companies needn’t diversify. Once you have an approved product, that’s the time to build a pipeline.” The other half of investors prefer platform companies. In that scenario, “If a lead fails and the company trades low, the management team turns over, and a new company emerges with a new product.”

WHEN EVERYTHING FAILS, REINVENT YOURSELF

That change that Oncolytics experienced is similar to the systematic reinvention that ultimately created Akari Therapeutics.

Akari’s story begins with Morria Biopharmaceuticals. Gur Roshwalb, M.D., CEO, had worked as a physician, as a healthcare research analyst for a leading investment bank, and as an investor at a venture firm. To gain operational experience, he joined Morria as CEO when it was near bankruptcy. “I renamed it Celsus Therapeutics, raised $21.7 million and got the company listed on NASDAQ,” he says.

Celsus Therapeutics’ lead candidate, a topical antiinflammatory drug for eczema dubbed MRX-6, failed to meet its endpoint in a Phase 2, showing no difference from placebo. “Even though we hadn’t pursued the technology we had, the company still had value,” Roshwalb says.

At that point, Celsus was a NASDAQ shell with $3 million in unencumbered cash. Its most obvious option was a reverse merger. A merchant banker introduced Roshwalb to Volution Immuno Pharmaceuticals SA, a British firm that was interested in Celsus’ NASDAQ listing and unencumbered cash. “Volution had promising Phase 1 data from Coversin, a small protein that inhibits the C5 complement, but it needed $45 million to advance to Phase 2 trials,” Roshwalb explains. Volution’s options were to pursue crossover financing or go through the lengthy IPO process. Merging with Celsus provided a quicker path to the public market than an IPO. “We closed the reverse merger in September 2015, forming Akari Therapeutics PLC, and did a $75 million private investment in public equity (PIPE) at the same time, just before the IPO window slammed shut.”

Roshwalb characterizes the deal as more of a marriage than a merger, albeit one that caused him to release most of Celsus’ staff and divide his time between London headquarters and New York.

FOCUS ON KNOWN BIOLOGY

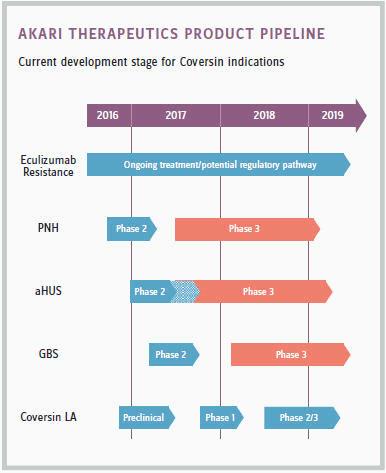

Akari abandoned Celsus’ eczema product and instead is focused on a next-generation C5 inhibitor, developing a platform therapeutic for orphan autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. This drug, Coversin, could compete with Alexion’s blockbuster drug Soliris in treating paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). In September 2016, Coversin received orphan drug status from the FDA. If trials proceed as expected, Roshwalb predicts Coversin could be second to market, introducing an alternative with a similar mechanism of action for an underserved patient population.

The key difference between Akari and Celsus, Roshwalb says, is that Akari’s drug has “a predicate biology that’s well-understood.” In contrast, the biology behind Celsus’s MRX-6 anti-inflammatory was still being discovered.

Companies fail, Roshwalb says, “by throwing good money after bad.” Failing quickly so companies can use their resources discovering what works is a goal in the biotech industry, but failures aren’t always easily recognizable. And, if a company has only one drug, abandoning it generally means abandoning the company. “Too often, people are unwilling to accept what the data tells them. We could have said there was an outside response to MRX-6 and continued our research. Instead, we realized the drug didn’t work and returned it to the university from which we licensed it.”

![]() "Too often, people are unwilling to accept what the data tells them ... We realized the drug didn’t work and returned it to the university from which we licensed it."

"Too often, people are unwilling to accept what the data tells them ... We realized the drug didn’t work and returned it to the university from which we licensed it."

Gur Roshwalb, M.D.

CEO of Akari Therapeutics

FAILURE CAN BE GOOD

For Celsus, failure triggered a change in direction. For Oncolytics, it resulted in laying a stronger scientific foundation. Both approaches have resulted in better molecules.

“Failures are critical to success,” Thompson says. “If something works every time, you don’t know its boundaries.” In learning those limitations, Oncolytics mined its data, discovering successes in subpopulations that may not have been considered if the drug had succeeded broadly in its early development.

Oncolytics and Akari took dramatically different approaches to ensuring that, despite setbacks, their companies survived. With an industry failure rate of approximately 90 percent, their ability to advance candidates into late-stage clinical trials speaks to their abilities to view their prospects dispassionately and assess their options with clear heads. Whether Oncolytics and Akari successfully commercialize their lead candidates remains to be seen.

"Too often, people are unwilling to accept what the data tells them ... We realized the drug didn’t work and returned it to the university from which we licensed it."

"Too often, people are unwilling to accept what the data tells them ... We realized the drug didn’t work and returned it to the university from which we licensed it."