ContraVir: Mapping A Circuitous Route To Value

By Wayne Koberstein, Executive Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @WayneKoberstein

The Enterprisers: Life Science Leadership In Action

If a person can be a legend, a company should be a saga. ContraVir contains both dramatic elements — a personal path through Big Pharma to small biopharma and an extended quest through a thick forest of data to find undiscovered treasure among some overlooked compounds. When I speak with CEO James Sapirstein, he takes me on a long journey full of the intertwining twists and turns of his own career and of the company he now heads. The story gives new meaning to “follow the data.”

ContraVir has two drugs now in mid- to late-stage development — one, dubbed FV-100, precisely targets the strain of herpes virus that causes shingles; the other, CMX-157, greatly multiplies the potency of its analog, the compound in Gilead’s product Viread (tenofovir) against the hepatitis B virus. Both candidates have a long history of miscarried trials and misapplied data from which the company has rescued them. Sapirstein had drawn on his own history with large companies such as Bristol-Myers Squibb and new players such as Gilead.

FV-100 is an antiviral drug that originated in the Welsh company Fermavir, founded in 2000 by the compound’s inventor, Chris McGuigan, at the University of Cardiff. When the company ran out of cash seven years later, it was acquired by Inhibitex, which subsequently developed two Hep C programs that overtook FV-100 as a company priority. In 2011, BMS (Bristol-Myers Squibb) bought Inhibitex and later, when the Hep C programs washed out, put the FV-100 asset up for sale. McGuigan, who by then had joined the board of the GI-company Synergy, convinced Synergy to bid and ultimately buy the asset. In 2012, Synergy incorporated ContraVir to develop FV-100.

FV-100 is an antiviral drug that originated in the Welsh company Fermavir, founded in 2000 by the compound’s inventor, Chris McGuigan, at the University of Cardiff. When the company ran out of cash seven years later, it was acquired by Inhibitex, which subsequently developed two Hep C programs that overtook FV-100 as a company priority. In 2011, BMS (Bristol-Myers Squibb) bought Inhibitex and later, when the Hep C programs washed out, put the FV-100 asset up for sale. McGuigan, who by then had joined the board of the GI-company Synergy, convinced Synergy to bid and ultimately buy the asset. In 2012, Synergy incorporated ContraVir to develop FV-100.

When Sapirstein joined the company in March 2014, he inherited a wealth of clinical data generated by three Phase 1 studies conducted at Inhibitex, mainly a large proof-of-concept trial. Significantly, the PoC study was a 350-patient trial, although favorable data in PHN (postherpetic neuralgia) reduction was not prioritized — due to an arguably shortsighted analysis by the sponsor.

“The original trial design was FV-100, 400 milligrams once a day, in one arm, and 200 milligrams twice a day, in another arm, versus valacyclovir [Valtrex], the standard of care for shingles. We conducted three new statistical analyses on their data, and we saw the two FV-100 arms showed a much higher-percent drop in PHN than the valacyclovir arm. Overall, FV-100 at 400 milligrams performed almost exactly like valacyclovir. But 10 percent of the patients in the FV-100 arm needed less narcotics to treat their PHN, and there was a 39 percent reduction in PHN scores.”

Until the reanalysis by ContraVir, says Sapirstein, FV-100 had always been saddled with the perception that the PoC study was a failed trial. Statistically, he says, FV-100 never reached its secondary endpoint, PHN reduction, because Inhibitex did not fully analyze the data, saying publically that it had already reached the primary virological endpoint. As a former BMS executive, Sapirstein believes Inhibitex more likely ended the trial early in anticipation of its sale to the large pharma, to concentrate on “packaging” the Hep C programs as the chief acquisition asset.

ContraVir took the reanalyzed data and reached out to the FDA for support in designing a new, Phase 2b trial for FV-100, this time reversing the primary and secondary endpoints so that PHN reduction became number one, ahead of decrease in viral load. Otherwise, the trial was essentially a doubling in size of the Phase 1 PoC, with 600 patients. As for the virological endpoint, total load reduction may not tell the whole story. Sapirstein says FV-100 differs from all other antiherpes drugs in not being “pan-herpetic” — it does not kill all strains of herpes like a broad-spectrum antibiotic kills a wide swath of bacteria species. Instead, ContraVir’s drug targets the shinglescausing strain specifically, varicella zoster, and it works in the dorsal root ganglion — possible reasons for its apparent effect on PHN in the early trial, he suggests.

James Sapirstein

CEO of ContraVir

To make sure the company could match speeds with the regulators, who were now enthusiastically supporting the program, ContraVir assembled a team of clinical development experts. According to Sapirstein, Nathaniel Katz, now on its scientific board, is one of the top PHN people in the world, having chaired or served on eight FDA pain-related advisory boards. Katz and Heidi Jolson, a former FDA director, helped write the Phase 2b protocol. “What kind of language should we write this in so it’s crystal clear to the FDA what we want to do? There’s not a better person to ask than Heidi Jolson,” says Sapirstein. The advice from Katz and Jolson included more than writing style, of course; a typical missive would be to use the proper precedent and an appropriate data set to support a given point.

The advice must have worked. In less than 24 hours after the company submitted its protocol proposal, the FDA committee granted the company a Type B meeting — one presuming the protocol’s approval — to discuss how the company should address the practical implementation of the Phase 2b trial. Later, the agency told ContraVir it could go directly to a Phase 3 trial using the same protocol, greatly accelerating its clinical development, regulatory review, and possible approval. The Phase 3 trial began in May 2015.

On the same day ContraVir heard the good news back from the FDA on FV-100, Dec. 18, 2014, it received a second tiding of joy: an effective patent extension for its Hep B drug, CMX-157, which it had licensed from Chimerix in late 2014. According to the company, CMX-157, as a prodrug of tenofovir, is 200 times more potent than the currently marketed compound (Gilead/Truvada).

Sapirstein has a personal connection to Gilead and Viread, having led the flagship product’s global launch there. He says he also has great plans for CMX-157, presumably as a second-generation form of tenofovir, for use as a common constituent of many different Hep B and HIV regimens.

“I believe CMX-157 will catch some people by surprise,” he says. “Right now it’s a Phase 2-ready asset. So we’re a tiny company with two late-stage assets, with one going into Phase 3 in the middle of this year, and if things go right with 157, we might surprise people with another Phase 3 asset as early as 2016.”

Sometimes, building an enterprise around a key asset requires taking a less than straightforward route to securing asset value. ContraVir mapped its own course, however circuitous, toward its goal — making use of sheer human talent and experience to mine a solid vein of data and support its claims on a novel product. If it can accomplish a similar feat with its second product, its building plans could expand by at least another exponential power.

FV-100 REBORN – DANCING WITH FDA

ContraVir’s CEO James Sapirstein is out to ruin the FDA’s reputation — the negative one too often repeated — that the agency just doesn’t care. In this case, the do-over clinical development of the company’s antiviral shingles drug, FV-100, has the regulators excited and all too willing to help, and the company’s main challenge is matching speeds with their guidance designing the drug’s new Phase 3 trial, which began in May 2015. Reversing the original endpoints in the former sponsor’s Phase 1 proof-of-concept trial, ContraVir’s new trial places reduction of post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) ahead of viral-load reduction as the drug’s lead indication.

WHY DO YOU THINK THE FDA IS GIVING FV-100 SO MUCH SUPPORT?

SAPIRSTEIN: We’re not going after just another me-too indication. This will be a disease-modifying indication, which no other drug on this planet has for shingles. There is not one other drug indicated for PHN. So we’re the only game in town. That is exciting for the FDA’s antivirology division, and they are always very cooperative with truly novel agents like FV-100. From the days of HIV, I remember, this division would accelerate approvals for truly new drugs. They work with you, they want to see you bring something to market. They don’t chastise, they recommend. When they granted us a Type B meeting, they said they are bringing in people from the pain division, as well as from the different stats divisions. I believe it is an effort to say, “You’ve done some great work on reanalyzing the previous Phase 1 data; this is what we recommend on the protocol.”

DID YOU ANTICIPATE THE AGENCY WOULD WANT TO ACCELERATE THE DRUG?

SAPIRSTEIN: We didn’t ask to go into Phase 3, we just wanted to meet with them, but we were hoping they would allow us to go into Phase 3. And quite frankly, for us, the worst-case scenario was that they would tell us this is a Phase 2b trial. Our hoped-for scenario was for the FDA to say, “You’ve already had over 350 patients receive this drug, your safety data base is pretty complete for Phase 2, and you plan on going into 825 patients on the next trial, a fairly large study. We agree in principle with what you want to do. Here are some changes and some suggestions we’re making for you, from a statistics perspective of types of patients, but we’re going to let you go into Phase 3. But you need two pivotal trials just like any other product.” For me, the grand slam would be they tell us, we like what you’re doing, we’ll let you go through accelerated approval with one trial, and you can move toward filing an NDA once you reach the middle of this trial. We’re a tiny little company, and we just resuscitated this program about a year ago, so we’re very pleased that the FDA allowed us to initiate a pivotal Phase 3 in June. We will likely have to complete a second pivotal trial as well, but the proposed plan for clinical development of FV-100, agreed to by the FDA, significantly shortens the development pathway for FV-100. This will save ContraVir considerable time and money.

THE CHIEFS OF CONTRAVIR — FROM EXECS TO ENTERPRISERS

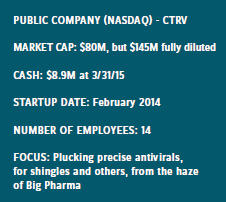

ContraVir has only been in operation since February 2014. Though it was incorporated in 2012, it lacked sufficient cash until then. Industry veteran and former Big Pharma executive James Sapirstein joined as the company’s first CEO a month later. Chief Medical Officer John Sullivan- Bolyai hails from Idenix, purchased by Merck, where he worked for only two weeks. Before that, he had been in the industry for more than 25 years, including several years at Roche, and before then at Valeant.

ContraVir has only been in operation since February 2014. Though it was incorporated in 2012, it lacked sufficient cash until then. Industry veteran and former Big Pharma executive James Sapirstein joined as the company’s first CEO a month later. Chief Medical Officer John Sullivan- Bolyai hails from Idenix, purchased by Merck, where he worked for only two weeks. Before that, he had been in the industry for more than 25 years, including several years at Roche, and before then at Valeant.

Sapirstein has 31 years in the pharma business — 17 in Big Pharma, including Eli Lilly, Roche, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. For BMS, he worked extensively in Africa and Asia, as part of the company’s efforts in HIV. After that, he came back to the United States and served as the company’s head of international infectious diseases. Then he was recruited by Gilead where he stayed for several years, until 2002, when Serono hired him as general manager heading its metabolic and endocrinology division. Because of his performance there, mostly cleaning house, he says, “someone convinced me that I should be a CEO.” Before going to ContraVir, he led Tobira Therapeutics and Alliqua, both of which enjoyed considerable success.

He started Tobira while doing a consulting stint at Domain Associates, working with the firm’s general partner Eckard Weber. He left five years later after Tobira was named New Jersey Bio Company of the Year in 2010. “I had a run-in with one of our investors who thought we should have sold the company. I tried to explain it was 2010, and no one was buying any assets right then unless it was in Phase 3.” He then struck out on his own, attempting to purchase NitroMed before joining Alliqua, which he fashioned into a wound care company, then left after landing a lucrative licensing deal with Celgene. He was finally attracted to the ContraVir start-up because of his background in anti-infectives.