Creating A Contingency Plan: Top 4 Pharma Concerns As Brexit Approaches

By Jennifer Ringler, Contributing Writer

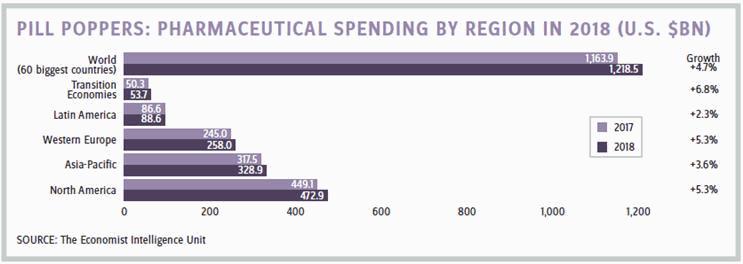

March 30, 2019 — Brexit D-Day — isn’t as far in the distant future as some might hope. For U.S. pharma companies with headquarters or CROs in the U.K., much needs to be decided, planned, and executed before that time to ensure a smooth transition. A recent report from the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), titled “Healthcare in 2018,” outlines the multiple challenges Brexit talks pose to the pharmaceutical industry.

ADOPTING EMA REGULATIONS

In order for currently existing drugs that have market authorization in the U.K. to be sold in the E.U. after Brexit, the EMA has said that pharma companies will need to set up additional offices elsewhere in the E.U. On Nov. 28, 2017, the EMA released its latest Q&A guidance about Brexit, which stated that marketing authorization holders (MAHs) established in the U.K. will need to be replaced with an MAH in one of the remaining EEA countries (E.U. countries plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway). This will require pharma to apply for a transferring of marketing authorization. It also means that the pharmacovigilance person (and pharmacovigilance master file) must reside and carry out business in an EEA member state.

“Of course, if the U.K. does reach a regulation deal before March 2019, then those E.U. offices may be unnecessary, but we can’t tell at this stage,” explains Ana Nicholls, healthcare analyst at the EIU and author of the report. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), U.K.’s pharma governing body, will take over responsibility for marketing authorization within the U.K., which means that in the future companies may have to duplicate applications unless a far-reaching mutual recognition deal is in place.

And that’s just for completed and approved drugs; those still in clinical development have additional hurdles to face. In April 2014, the E.U. passed new clinical trial regulations, which were planned to take effect in October 2018. According to the EIU report, the implementation has now been delayed until 2019, and Nicholls says it’s “not quite clear” whether the U.K. will decide to implement them or, essentially, create their own from scratch under the MHRA. Arguments for the U.K. forging its own way include the idea that doing so could cut through a lot of bureaucracy, allowing a much quicker drug approval process than the rest of the E.U. currently sees under the EMA. The argument against is that if the U.K. does adopt its own laws, drugs manufactured under those laws won’t be recognized as approved outside the U.K., unless a deal is struck between the two countries. Meaning, the limited marketability of drugs developed under post-Brexit U.K. law will likely motivate pharma companies to concentrate on approval in E.U. markets, leaving the U.K. behind.

![]() "If they can’t ship things so easily, maybe it makes more sense to house the manufacturing in one place or the other, rather than swapping across borders."

"If they can’t ship things so easily, maybe it makes more sense to house the manufacturing in one place or the other, rather than swapping across borders."

Ana Nicholls

Healthcare Analyst, Economist Intelligence Unit

RECRUITING AND MAINTAINING A WORK FORCE

In terms of how, exactly, Brexit will affect the pharmaceutical work force, “That’s another issue that still isn’t settled,” Nicholls says. “At the moment, it looks likely that anyone who currently resides in the U.K. can stay; it’s not that anybody will get kicked out.” Pharma should be keeping an eye on ensuring top-quality talent is available down the line. Nicholls says it’s likely that some type of “immigration system” will be implemented in the U.K., but the details of what that will look like are anyone’s guess.

As mentioned in a previous Life Science Leader article by authors Cameron Cooley and Chris James, “Indications are that the U.K. government is pursuing a ‘hard Brexit,’ which would end the right for other E.U. nationals to work in the U.K. without visas.” This could mean that recruiting top talent from the E.U. will become more difficult, as qualified candidates seek to work within the E.U. to avoid the complications of international work arrangements. Much like the red tape around post-Brexit EMA regulations, this complication could contribute to the newly independent U.K. becoming less desirable over time for pharma.

RETAINING MEDICAL FUNDING

Another major hit to pharma from Brexit could be the loss of scientific and medical funding coming in from the E.U. The U.K. has had significant funding from Horizon 2020, an E.U.-run research and innovation program offering €80 ($107) billion of funding over seven years (2014 to 2020) that is seen as “a means to drive economic growth and create jobs,” according to the program’s website. Nicholls notes that the U.K. has been one of the “biggest beneficiaries” of the program. The U.K. government has pledged to fund any research already underway until 2020, regardless of the E.U. negotiations. However, the U.K.’s involvement in future E.U. science programs is among the issues that still need to be discussed in ongoing Brexit talks.

But Nicholls sees the loss as an opportunity. “It could give us more motivation to work in scientific programs in the U.S., India, or China,” she says. “One of the things about the U.K. science programs is they do get fairly widely cited; international citations are a widely used measure of the success of a scientific program. It may be that we still manage to get enough international programs from other sources to balance out the loss of that funding.”

ENSURING THE SUPPLY CHAIN

There is a lot riding on the “what ifs” around post-Brexit supply chain; how negotiations play out here could potentially mean life or death for patients, as well as businesses.

“The main concern the pharma industry is having is, will there be a point after March 30 where all their goods are stuck in transit because they can’t ship them across the border from the U.K. to the E.U. without the right paperwork?” Nicholls says. “It is conceivable that this might be the case for a few days.”

Her advice for pharma on this front is to have contingency plans in place including a stockpile of currently approved drugs as well as raw materials for manufacturing, both inside and outside the U.K. “In the long term, pharma companies need to look at the whole supply chain and consider, if they can’t ship things so easily, maybe it makes more sense to house the manufacturing in one place or the other, rather than swapping across borders.” Such a contingency would require significant additional planning and cost on pharma’s part.

THE WAY FORWARD

There are clearly still quite a few details that need to be hammered out before March 2019. “But I don’t think they will be hammered out by then,” concedes Nicholls. She’s not the only one who has realized this; on November 28, the same day the EMA released its latest Brexit guidance, several associations representing the European and British life sciences industry collectively released a statement calling for a transition period and a post-Brexit cooperation agreement. “We urge Brexit negotiators on both sides to agree on a transition period that adequately reflects the time needed by companies, as well as all relevant authorities at E.U. and national level, to adapt to changes in view of the U.K. exiting the E.U.,” the statement reads, in part. “Even in the context of the Brexit negotiations where all sectors are looking for clarity on the future, it’s important to recognize that medicines are different. Our goal is ensuring that patients across Europe and the U.K. are able to continue to access safe and effective medicines through Brexit and beyond, and to ensure that there is no adverse impact on public health.”

"If they can’t ship things so easily, maybe it makes more sense to house the manufacturing in one place or the other, rather than swapping across borders."

"If they can’t ship things so easily, maybe it makes more sense to house the manufacturing in one place or the other, rather than swapping across borders."