How Rebiotix Avoids The Typical Biopharma Startup Missteps

By Wayne Koberstein, Executive Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @WayneKoberstein

The Enterprisers: Life Science Leadership In Action

A straightforward purpose and premise were the words that came to mind in my first impression of this company. Lee Jones, the CEO and cofounder of Rebiotix, describes building the company in an “of course, this is how you do it” manner. The larger issue — whether the company’s Microbiota Restoration Therapy (MRT) platform will succeed in a somewhat besieged field — can only be resolved over time. But it will most likely be biology that decides the matter, not the typical lack of clear direction or organization that plagues so many biopharma startups.

As I write this, a Rebiotix rival, Seres, is encountering its own biological challenge, with disappointing midterm results from a Phase 2 trial of its encapsulated substitute for fecal transplant. The so-called failure by Seres’ drug and a few other tentative setbacks with similar competitor products have all the usual pundits with a congenital surplus of confidence rushing to be first to predict the general downfall of microbiome-drug development. As the opinionators accuse developers of excessive claims based on scant evidence, they use the same evidence to rush into a sweeping judgment of the entire space. My guess is that the microbiome field, like any new area of medical promise, will see numerous failures or setbacks before it produces an unqualified success. Thus, in this article, I choose to concentrate on the company-building aspects of Rebiotix rather than conjecture on how its product development will ultimately pan out.

IMPLEMENTING INVENTION

Jones had already put in more than 30 years developing medical products before hitting on the idea of a fecal-transplant replacement in patient-friendly form. (See the sidebar, “School of Enterprise.”) Jones and her partners, Michael Berman and Erwin Kelen, founded the company in 2011, all three with a long history in building new businesses. To date, they have raised $30 million in two series, all from private wealthy individuals. Now they are out looking for the company’s next round of funding from institutional investors.

Jones had already put in more than 30 years developing medical products before hitting on the idea of a fecal-transplant replacement in patient-friendly form. (See the sidebar, “School of Enterprise.”) Jones and her partners, Michael Berman and Erwin Kelen, founded the company in 2011, all three with a long history in building new businesses. To date, they have raised $30 million in two series, all from private wealthy individuals. Now they are out looking for the company’s next round of funding from institutional investors.

Unlike Seres and others, Rebiotix did not try to single out the useful bacteria and separate it from the useless. It took a much simpler approach — collect stool from healthy individuals, process it into safe and stable products, and deliver it in much more tolerable ways than the conventional transplant. The lead product, RBX2660, is delivered by enema; the next in line, RBX7455, by capsule.

“We knew that fecal transplants worked, but people were using them as a technology of last resort because it wasn’t industrialized,” says Jones. “I was good at doing things like that, and we thought, ‘Let’s turn this into an industrialized product, figure out what we need to do to make it consistently high quality, stable, and patient-deliverable on demand.’ So that’s what we did.” (See the sidebar, “Put It Where?”)

A simple idea cannot guarantee a simple execution, of course. “I thought, how hard can this be, the raw material is human stool? But I found out there were no precedents set — no regulatory precedent, and no physical precedent,” Jones says. “Nobody even knew how to quantify stool or what was in it, how to strip the microbes out, how to preserve the microbes, because you can’t culture them all. It took us more than a year to figure out how to measure, quantify, process, and preserve it.”

Rebiotix first approached the FDA in 2012, believing its product would be classified as a tissue transplant. The agency balked, however, because human-resident microbes are not considered human tissue. Instead, the FDA directed the company to submit its product as a biologic-drug product, handled by the Office of Vaccine Research and Review (OVRR) in the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER).

Having a clear regulatory track inspired the company to take a longer-term view of its product development. Although Jones and her team believed the enema form would work well as the first generation product, greatly improving on fecal transplants, they would ultimately need to take the patient-friendly concept a step further — to the form of an innocuous, commonplace capsule, devoid of any obvious link to its point of origin. Again, it was a simple idea; its implementation would be an invention in itself.

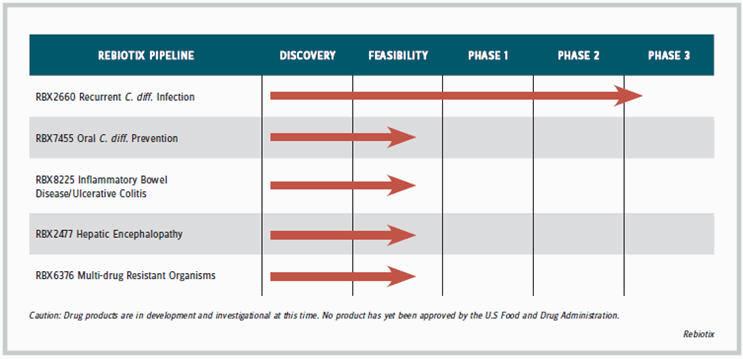

“I remembered how products like insulin and estrogen got started,” recalls Jones. “Estrogen [Premarin] came from mare urine. New treatments often start out with a natural product that maybe isn’t so appealing, and then as companies learn more, they can formulate or package the product differently.” Its enema product is in Phase-3 development for treating C. difficile (C. diff) infection, which usually requires only a single administration; the capsule product is in earlier-stage development to prevent C. diff. and for prolonged or chronic use to treat conditions such as ulcerative colitis, hepatic encephalopathy, and infection with multidrug resistant organisms (MDRO). The company is developing a separate oral formulation for each of the indications requiring long-term therapy.

Although MDRO infections can occur anywhere in the body, they tend to hide or “colonize” in the colon even after a patient has recovered, making disease recurrence and transmission possible for a long time. Rebiotix has just treated its first patient with an MDRO urinary tract infection in a prospective clinical study at Washington University in St. Louis.

An oral replacement for fecal transplants, though, requires a way to store microbes at room temperature. “We had to invent that, too,” says Jones. The microbiota in the gut are anaerobes, so they will die when exposed to air, but in capsule form the microbes cannot be stored in water. “We had to figure out a way to preserve them in a dried format, picking just the right excipients to keep them away from oxygen and water, and then encapsulate them. Today we have achieved more than a nine-month room temperature stability with our oral form, and about two years on the enema form, which is frozen. We have industrialized it so that you can ship and deliver it to patients in a way that fits in with the physician practice.”

The company screens donors for disease-causing organisms, based on a list of species maintained and periodically updated according to an agreement with the FDA, but it generally retains the rest of the microbiota regardless of whether every species has a clearly identified role in GI health.

“Our premise was that humans have evolved with a gut microbiome for millennia, and in a healthy person, generally whatever is there works as a community to keep the person healthy,” Jones says. “So our goal was to replicate as much of that community and keep it as intact as we could. We believe you really can’t overdose somebody; the substance is not toxic, so the safety issues are minimal. We’ve treated more than 300 patients and we have seen no transmission of any kind.”

TAKING CAREFUL AIM

The therapeutic targets of Rebiotix have emerged along with scientific advancement in the field since 2011, albeit through a careful weeding and selection of particular indications. From the predominance of C. diff infection as the target of choice, the number of conditions now in testing for microbiome therapy by all companies has expanded to more than 20. “We looked for conditions for which available treatments are inadequate or leave room for a product that isn’t the end game — such as ulcerative colitis — where patients begin on a mild medicine, but if that doesn’t work, have to go to a very harsh biological.”

Jones says the company chose indications that offered measurable endpoints “so you weren’t left guessing whether or not the product was effective.” It also aimed at areas where its products’ pricing would raise the least resistance. All in all, she says, the company applied nine criteria to its candidate indications, in consultation with its physician advisory board, to narrow its focus to the five conditions now targeted in its pipeline. Yet serendipity played a role in some cases, as she describes:

“In our C. diff study, we also looked at patients infected with vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE), which causes a severe blood disease if it gets out of the colon. About 40 percent of the C. diff patients were infected with VRE, and we found our treatment could clear the VRE in them as well. We have published clinical data on that.”

In a second case, the company got involved with a pediatric gastroenterologist who was interested in testing its MRT approach in pediatric ulcerative colitis, a disease more tractable to treatment at a pediatric level, because it leads to ever greater inflammation over time. “We believe there’s a way to stop the cascade of events before the patients get to be adults. So we’re doing a trial with a gastroenterologist group in Canada, which had achieved good results in a randomized adult ulcerative-colitis study with their fecal transplants. Now they are using our product in a blinded study for pediatric ulcerative colitis.”

SMALL-CAP SPACE

The microbiome is vast. “It is mostly an unexplored universe in its countless species, range of disease-affecting roles, and abundance of possible therapeutic mechanisms and targets. Despite all the hyperbole now circulating over the space, it is still at a stage where the smattering of enterprises operating inside it do not constitute competition so much as confirmation of the microbiome’s medical potential. (See “Companies to Watch,” Osel, April 2016.)

“There are many different kinds of companies looking at the microbiome in many different ways,” says Jones. “We’re using the microbes themselves as a therapeutic agent. Others are using metabolites from the microbes as a therapeutic option. Some are genetically altering the microbes to improve their effectiveness. This is a new arena for me, but it is also a new arena for almost everyone, which is why I can play here. If it were a pure drug product, I probably wouldn’t be qualified, but because it’s an open playing field, anyone who’s interested can learn. For me, this was a way to get into something I thought would be tremendously interesting. I’ve met experts all over the world, and they have been my teachers. I tracked them down, brought them onto my advisory board, and learned what was going on.”

Out of skillful technological invention, business organization, and therapeutic selection arises the company’s straightforward strategy: Anticipate and fill customer needs with patient-friendly products in unserved or underserved therapeutic areas. As the other companies help pioneer the microbiome territory, Jones remains confident in her company’s position.

“We’re the most clinically advanced of any of the companies that are doing any work with the microbiome, and the first company to take a multifaceted microbial mix through the FDA. We’re about a year ahead of our nearest competitor with a slightly different product.”

It’s a risky business, drug development, no matter how well you manage it. Yet most people would not want their company to fail because of bad management. We admire the intrepid heroes who jump into the chilly waters of real business without a wet suit. We should also spend some time heralding the people who have achieved sufficient experience, knowledge, and skills in executive management and apply those assets effectively from the point of startup and beyond.

PUT IT WHERE?

Actually, says CEO and cofounder Lee Jones of Rebiotix, the enema form her company is developing with its lead product, RBX2660, is a significant improvement over the fecal transplants it is meant to replace, though its next-generation oral form will be even more patient-friendly.

JONES: We picked the enema delivery for our first product because when we got started, most people were delivering fecal transplants with colonoscopies or nasal gastric tubes. That causes patients a lot of problems, particularly elderly and sick people. We looked through all the literature and found that enemas had the least procedure-related complications and had been done for a number of years. That is how we chose our original formulation. One of our main competitors chose to develop a frozen oral pill as their first product, but we think our enema is a better option because, unlike the frozen pill, the enema may not need a bowel prep. It is like getting a flu shot. Patients go in, get the enema, get up, and go home. Because the bowel prep tends to be the worst part of any procedure, and most people hate that part, we thought patients would be more tolerant to the enema.

We’ve now finished our Phase 2b multicentered, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with RBX2660 in C. diff infection, and the results of that will be announced this fall at one of the major medical conferences. We are getting close to starting our Phase 3 trial. Our next product, RBX7455, the oral form, should be entering the clinic in the fourth quarter this year.

SCHOOL OF ENTERPRISE

Personal histories of company founders and leaders are more fun in their own words. Rebiotix CEO and cofounder Lee Jones recounts the highlights of her career that schooled her in how to start and run her company.

JONES: I am an engineer by training and also have a business background, and I have spent more than 30 years developing new technologies and introducing them to new markets. I worked for 14 years at Medtronic, and I was involved in multiple startups within that company, including its angioplasty, vascular graph, and InterStim [surgically implanted neurostimulation device for urinary incontinence] programs. Then I left there and ran my own business. I sold that and ended up at the University of Minnesota Office of Technology Commercialization, where I was looking for my next thing to do. They gave me a job in the Diabetes Institute, trying to develop cellular transplant therapies to cure Type 1 diabetes, but we couldn’t get that out of the pre-clinical animal stage, so I moved on. Someone in the Office of Technology Commercialization told me about fecal transplants, and I thought, “How stupid of an idea can that possibly be?” So I volunteered to help the university scientists see if it was a viable business.

At that time, it seemed no one knew anything about the microbiome, so I was trying to figure out how fecal transplants would be regulated, because my specialty was taking products from early stage through the clinic and into the market. Then, the scientists got funding and went somewhere else. But I decided that this was such a cool concept, and the more I learned about it, the more excited I got. First, I thought about making a more patient-friendly product that could replace the fecal transplant. I started thinking, “Wait a minute, it’s not like rocket science.” At least that’s what I thought at the time. “I can find my own scientists and do my own work.” So I found a partner who had looked at a similar opportunity a year before but couldn’t get it funded. The two of us formed a partnership, brought in a third partner who knew financing, and started Rebiotix in 2011.