Leaked Emails, Physician Reg Signal Risks For Rx Industry

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

As the most bizarre and unpredictable election season draws to a close, scrutiny is turning to wikileaked emails among senior officials in the Clinton campaign who are licking their chops to take on the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare policymaking by the executive branch.

As the most bizarre and unpredictable election season draws to a close, scrutiny is turning to wikileaked emails among senior officials in the Clinton campaign who are licking their chops to take on the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare policymaking by the executive branch.

WikiLeaks dumped thousands of emails between John Podesta, chairman of the Hillary Clinton campaign, and other Clinton advisors that revealed a general disdain for the pharmaceutical industry and looked for openings to exploit the industry for political gain.

When biotech stocks swooned last fall on Hillary Clinton’s tweet that Turing’s aggressive pricing was “outrageous,” Clinton campaign strategist Ann O’Leary gleefully exclaimed “We have started the war with Pharma!”

Leaked emails also showed O’Leary probing opportunities to attack President Obama’s nominee Robert Califf for FDA Commissioner as having “real ties to the drug industry.” (Before joining the FDA, Dr. Califf was a professor of medicine and vice chancellor for clinical and translational research at Duke University.)

Another Clinton adviser, Brian Fallon, supported the idea, responding to O’Leary, “As we consider fights that fit into the larger themes we are trying to promote, this seems like a good fight to have.”

While those attacks were ultimately never launched, it certainly shows the mentality of the Clinton camp that they would undermine their own party’s president for political gain. And just as important, they view attacking the pharmaceutical industry as very politically appealing.

This is the political environment the industry is facing should Hillary Clinton win the White House.

MACRA REG STARTS SLOW BUT COULD PENALIZE DOCS FOR RX PRESCRIBING

In mid-October, CMS released a 2,398-page tome implementing the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) that fundamentally changes how physicians will be reimbursed under Medicare. This law is supposed to simplify how physicians are paid.

Although it will take weeks for the white-shoe law firms to pore through the thousands of pages of regulations, a key takeaway is that the agency bowed to physician community and congressional pressure to minimize penalties on poor performing physicians in the first year of implementation. Indeed, nearly one-third of physicians will be exempted entirely because CMS raised the low-volume threshold to $30,000 or 100 Medicare patients, and another 8 percent are exempted from penalties for other reasons.

The law provides two tracks for physicians: They can remain in a fee-for-service system and participate in the “Merit-Based Incentive Payment System” (MIPS) or accept bundled or capitated payments under new Alternative Payment Models (APMs).

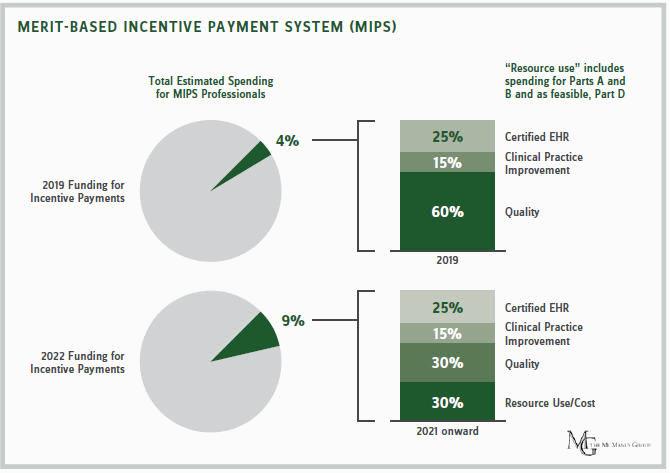

CMS expects most physicians — 94 percent — to remain in MIPS. Since there is a lag between the performance and payment years, in 2019, the MIPS initially puts 4 percent of physicians’ payments at risk based on how they comparatively perform in delivering quality, expend healthcare resources, and use certified electronic health records (EHRs). By 2022, that portion grows to 9 percent, which policymakers believe can produce substantial behavioral change.

The political pressure to launch the new program as painlessly as possible led the agency to eliminate penalties on any practice that reported just one quality measure in each of two categories next year or report the required measures for EHRs.

The final rule provides greater flexibility for physicians — dropping the minimum reporting requirement from the proposed rule of 80 percent of Medicare patients to 50 percent of Medicare patients. Similarly, the all-or-nothing approach on EHR incentive programs is replaced with a scheme that permits a physician to choose five of 11 measures.

Acting CMS Administrator Andy Slavitt said, “Ultimately, we believe that we’re not looking to transform the Medicare program in 2017; we’re looking to make a long-term program successful.”

However, it is a zero-sum game. Penalties from poor-performing physician practices finance bonuses of high-performing practices. The flip side of fewer penalties is that many physician practices are wondering why they made the investments to purchase EHR technology and train their doctors to report on quality and resource measures. Bonuses will be de minimis.

Dr. Fred Rosenberg, president of Illinois Gastroenterology Group, remarked, “The goal of MACRA linking reimbursement to outcomes, quality, and cost is laudable, and by limiting downside risk, CMS appears to have made an effort to make participation possible for most physicians. Unfortunately, it appears that rewards for program success have been correspondingly decreased. Physicians may determine that the initial and ongoing costs (both in time and effort) for participating in MIPS, and possibly even APMs, may be greater than any financial upside.”

To the life sciences sector’s relief, CMS will not be judging physicians on resource and cost goals in the first year of the program. Physicians’ resource use was supposed to constitute 10 of their score in 2017. The resource-use metric will now commence in 2018 and eventually increase to 30 percent of a physician’s score by 2021.

Tying physician reimbursement to the costs they generate in the healthcare system could be problematic for emerging health technologies and newer drug therapies. The rule attributes to primary care doctors all the cost of the care for the patient, including prescriptions ordered by specialists to whom they’ve referred patients for advanced treatments.

This means there is a built-in disincentive to refer to specialists who prescribe new treatments or expensive drugs to treat complicated conditions. Many drugs and other treatments that may be seen as the standard of care do not yet have a quality metric associated with their use, as consensus guidelines typically lag clinical practice and peer-reviewed literature. As such, this rule could have a chilling effect on patient access to potentially life-saving or extending treatments for conditions such as advanced prostate cancer. Without a quality measure for such drugs, physicians face only downside risk for prescribing such drugs.

Nonetheless, the one-year reprieve provides breathing room for stakeholders to marshal data and analysis showing why this policy should be altered before it goes into effect in 2018.