Lilly Lives On — And Prospers

By Wayne Koberstein, Executive Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @WayneKoberstein

At 140 years, setting the industry benchmark for constancy and growth.

Eli Lilly and Company last appeared in these pages just short of two years ago, in a story based on our conversation with chairman, president, and CEO John Lechleiter — “Lilly’s Tale of Trial and Tenacity” (June 2014). At the time, the company faced many doubts, and more than a few loud doubters, concerning its struggles to overcome patent expirations for its most lucrative products. Each time it encountered a setback in clinical trials, the predictable swarm of tweets, trade news, and commentaries derided Lilly as a lackluster performer. Now, the critics seem quieter as the company points to big changes and achievements in the past two years.

That is one reason we return to visit the company again, this time in an expanded form, featuring not only Lechleiter but also a group of top executives leading its two largest businesses, Bio-Medicines and Diabetes, plus critical functions for Lilly as a whole, manufacturing and quality. Coincidentally, our multifaceted update comes in the context of Lilly’s history of 140 years — an extraordinary life span for a U.S. company, perhaps due to the company’s constancy in culture and mission. For Lilly appears to have achieved what a number of other Big Pharmas have not — global-scale growth in value without reliance on repeated M&As.

Starting with Lechleiter’s update on the company overall, we look at each of the organizations headed by the following: David Ricks, president of Lilly Bio-Medicines; Enrique Conterno, president of Lilly Diabetes; Maria Crowe, president, Manufacturing Operations; and Fionnuala Walsh, senior vice president, Global Quality. In a separate article, our chief editor Rob Wright writes about the critical role of Lilly’s chief financial officer, Derica Rice. Throughout this expanded feature runs a unifying theme: how corporate continuity complements corporate change.

History Made Now

A meaningful review of the past should shed light on the present. As Lilly celebrates its 140th birthday, it has a natural reason to look back to its beginnings for a proper perspective on its current state. In 1876, the company’s namesake and founder, Eli Lilly, opened a lab to produce reliable, high-quality medicines he found lacking in his Civil War experience and afterward in the country in general.

A practicing pharmacist before the war, Lilly assembled and led his own company, holding the rank of colonel in the Union Army. He saw plenty of death, injury, and disease during his time in combat and as a prisoner, usually in the worst of conditions for medical care and supply. But the state of medicinals across the expanding nation was not much better once the war ended; people had no way of confirming who made them or what was in them. Lilly eventually hatched the idea for a new kind of pharmaceutical supplier placed in the heart of the Midwest — one that would adhere to superior quality standards and help drive the development of prescribing by physicians. From that little acorn, initially a tiny family enterprise, the great oak of the Lilly company has grown.

John Lechleiter, a “Lilly history wonk” by his own description, takes up the story in the 20th century, with a seismic event that changed the company’s course for then, now, and into the future. “An ambitious and capable research director with Lilly at the time, Dr. George Clowes, got on a train Christmas Day in 1921 and traveled from Indianapolis to Connecticut to hear Frederick Banting of the University of Toronto present a paper at the American Physiological Society on the discovery of insulin. Clowes then began to urge Banting, his assistant Charles Best, and his boss John Macleod into collaborating with Lilly.”

The company consummated the insulin deal with the University of Toronto in May 1922, with Colonel Lilly’s grandson and namesake, Eli Lilly, then-CEO, signing. Banting and Macleod won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1923 for their insulin discovery.

“That deal brought the company into the modern era,” says Lechleiter. “When we launched insulin in 1923, it was literally a life-saving drug, and it has since stood the test of time. Unfortunately, diabetes remains unconquered, and we still need insulin today. It’s Lilly’s largest single business after 100 years. But I believe the decision to supply insulin commercially typified our willingness to take risks, coupled with scientific excellence as embodied in Clowes, who recognized what an opportunity this presented and then applied his doggedness and determination.”

The company’s original business model — creating a high-quality standard for all pharmaceuticals — guided many of its actions in setting up the development and production of insulin, then refined from animal pancreases by methods the company invented to ensure purity and batch consistency. Long before FDA regulations existed, Lilly did clinical testing in 1922 and 1923 to ensure that, when it launched the product, it could tell physicians how to use it. Eventually, going beyond its own internal initiatives, Lilly would play a leading role in establishing the FDA and its regulatory authority.

Lechleiter cites the next formative event for the company, still relevant today: the development of its expertise in drug fermentation, beginning with penicillin production in the 1940s. Lilly also used a fermentation process to produce more than half of the Salk polio vaccine for U.S. children in the mid-1950s. “The fermentation capability enabled us to discover and produce molecules such as vancomycin, still today one of the last lines of resistance against MRSA; erythromycin, another Lilly discovery in the 1950s; and the cephalosporin family. Our fermentation capability also carried over to our partnership with Genentech in the late 1970s to develop biosynthetic human insulin,” he says.

Biosynthetic insulin was an event in itself. When Lilly and Genentech launched Humalog in 1983, it was the first biotech therapeutic ever approved — not only a first in technology but also the beginning of an entire industry sector whose legacy endures. “It is still fermentation technology that enables us to make all of our biotech products,” says Lechleiter.

The fourth transformative historical event for Lilly, he believes, was its introduction of Prozac (fluoxetine), the world’s first serotonin-uptake inhibitor for depression — both for the impact Prozac had on the company and also for the huge impact it had on the treatment of the condition, largely bringing mental illness out of the closet. “With biosynthetic insulin and Prozac in the 1980s, the company began to move beyond antibiotics and animal-insulin and into biotechnology and neuroscience as key areas of growth, which they continue to be today.”

Lilly’s current neuroscience pipeline is mainly focused on neurodegenerative diseases and pain, and the biggest news generator there is its drug for Alzheimer’s disease, solanezumab, an anti-amyloid plaque antibody. (See also the sidebar, “Tracks of Growth,” and the section, “Therapeutic Transformations.”) Lechleiter sees the challenge of developing the treatment as a long haul. “We have been working in Alzheimer’s for 27 years. We’ve had ups and downs, mostly downs, but we have made progress. We worked on Prozac and research related to Prozac from the 1950s through the 1970s.”

Sharing Value

Lechleiter asks rhetorically, “How do you sustain that kind of investment over such a long period of time?” He answers, “You can only do it if you have the promise of being rewarded for the risk that you take. We reward risk-taking in the United States with free pricing, which of course the company must do responsibly.”

Lilly competes on price to some extent, meaning its price points for any key product take into account the relative pricing of comparable agents from other companies in the same class. Therapeutic “equivalence,” where meds with different mechanisms for the same indication must compete against each other in formulary selection, widens the competitive field, as Lechleiter notes: “There is no product of ours out there today that doesn’t have a competitor.” He has cited a range of discounts from the company’s average list prices of up to 33 percent for commercial health plans and 81 percent for government payers.

“It is not just price, but price is certainly a lever, and sometimes you have to offer a discount or a rebate for pharmaceuticals as you would in other industries and markets. It’s not a perfect market, but it’s a better market than most people believe it is.”

So, does pricing moderation compromise shareholder value — or enhance it? In Lilly’s case, a theoretical answer may not be relevant, because the numbers speak louder; whatever the company is doing, the results look positive. Since the industry’s nadir in 2009, Lilly has boosted shareholder return by about 225 percent, or about 125 percent more than the average of its peer group. Of the top 12 pharma companies in total shareholder return, Lilly is now the third company on the list, leading much larger companies such as Pfizer, Novartis, and Merck. Of interest, Lilly stands only in the midteens among the top pharma companies by sales.

“Shareholder value follows from all the things that you do, and in our industry, it’s all about creating value through your pipeline,” says Lechleiter. “Now, when I look at our pipeline chart, I see lots of positive data readouts. Ultimately, that’s what sets the candidates apart.”

Lechleiter still believes a major source of value for Lilly and its shareholders is that the company has not been distracted by major mergers and acquisitions. “By pursuing our own course, we are creating value for all of our stakeholders. You can expect Lilly will continue to make robust but appropriate investments in R&D and do more preclinical and early clinical-stage deals. But we already have great opportunities to take leadership positions in our therapeutic areas of focus, based on the molecules we have on the market today and the ones we anticipate launching.”

Markers Of Progress

Since we last featured Lilly in these pages, the company has been busy living up to its own expectations — reaching goals or markers by which outsiders can judge its post-YZ (i.e., the patent loss time period spanning 2011 to 2014) recovery and growth. In 2009, the company issued a guidance listing four strategies it would employ as it launched new products and reorganized itself into the business-unit structure: grow revenue, expand margins, sustain flow of innovation, and deploy capital to create value. As it gave projections of revenue, income, and cash flow, it promised to maintain its annual dividend and “invest robustly” in R&D. It also pledged to reduce operating expenses to less than 50 percent of revenue by 2018.

To no one’s surprise, the company cut jobs and closed facilities to keep that promise. But it also performed a major upgrade on its insulin plant in Indianapolis. Our exchanges with Maria Crowe and Fionnuala Walsh, covered in the following pages, are especially relevant to changes in a critical component of operations: manufacturing.

But cost-cutting and efficient infrastructure have not been the only avenues to reducing OPEX; boosting revenue and margins has had a complementary effect. As revenue grew by almost five percent in 2015, OPEX fell to 54.7 percent of revenue, from 57.3 percent the year before. In January 2015, the company announced it was on track to meet the guidance goals, and it emphatically reaffirmed its progress this year. “Essentially, we have a fixed asset base into which we’re launching new products,” says Lechleiter. “We’re really leveraging our investment in OPEX with all those launches.” Lilly has brought eight new products to the market since 2014.

In addition to the financial progress, the launches speak to how well Lilly is fulfilling its third pledge: to sustain the flow of innovation. That includes its R&D investments internally and externally, reflecting the fourth and final pledge — to deploy capital to achieve its objectives, while returning excess cash to shareholders through dividend and share repurchase. “What I’ve been talking about for the last year or so is basically about how well we are keeping those four commitments,” Lechleiter says, “and they will guide us, I’m sure, for another four or five years.”

Coming back to how the past informs the present — Lechleiter paraphrases William Ford, great-grandson of Henry, on Ford Motor’s 100th anniversary in 2003: “Bill said something like, ‘We’re happy to celebrate our history, but we’re even more excited about creating new history.’ At Lilly, we look back with a great deal of pride to our history, and we find relevance in it — it’s not just dusty old volumes in a bookcase. Because of that history, we understand better why we are what we are today. We still hold to the values the Lilly family articulated, and lived, in the first 100 years of the company when they were involved, so our history is very relevant to us. But our goal is to take what we have learned from our past and build a brighter future for the company.”

In the following, we look more closely at the Lilly organization’s striving to apply the constancy of its corporate history and values to the ongoing challenge of necessary change in each of their areas.

Therapeutic Transformations

Lilly has defined several of its core businesses mainly by the therapeutic areas each covers. Lilly Bio- Medicines has marketed products in neuroscience, cardiovascular, urology, musculoskeletal, and autoimmunity. Its development pipeline concentrates mainly on neurodegenerative disease, pain, and immunology. David Ricks has done some thinking about the origins of Bio-Medicines, which he heads as president, and he sees much of the company’s heritage and traditions as built-in fundamentals of the business he leads.

“Everyone recognizes technology and science as the sources of our growth and improvements for patients. Our success with insulin and antibiotics led to the neuroscience and post-Prozac era, where we professionalized and ramped up research tremendously. We also share a strong commitment to leadership development — bringing up strong leaders from within the company.”

For the first century of the company, three generations of the Lilly family led from the top. But family involvement ended after the death of Eli Lilly, Jr., eldest grandson of the founder, in the 1950s, and it became common for the CEOs and other top executives to spend large parts of their careers at Lilly working their way up. At the same time, Ricks notes, many Lilly alumni went on to join the executive teams of other leading industry companies. Ricks came to Lilly in 1996 and rose through the ranks mainly in sales and marketing. He formerly headed the company’s China subsidiary and is past president of Lilly USA, becoming head of Lilly Bio-Medicines in 2009.

In his view, a fundamental advantage for the company is yet another inheritance from the Lilly family. “They gave us a commitment to a culture based on the core values of compassion and respect for people, excellence — our slogan is take what you find and make it better and better — integrity in speech and word, and quality in our products and processes.”

Leading With Neuroscience

Although the name of the business is Lilly Bio-Medicines, Ricks says the intention was not to make it responsible for all of the company’s biologically produced medicines. Two of the other business units, Diabetes and Oncology, are dedicated to single therapeutic areas, so the bioengineered products within those areas are theirs.

“We used the word ‘biomedicines’ to talk about where the technology was going, because even outside of diabetes, we were mainly capitalizing on biotechnology to invent our way to the next version of Lilly,” Ricks says. “That was the challenge we faced in 2009: With the cupboard bare, we would be losing close to $10 billion in revenue due to expired patents during the following four years. And as it turns out, the majority of the company’s pipeline now consists of biologics, and in my group, all but one of our late-stage projects are biologics.”

Bio-Medicines does have a defined therapeutic focus, however, which is now narrowing and realigning in drug development to neurodegenerative disease, pain, and immunology. Of the highest priority in its pipeline is the Alzheimer’s program led by solanezumab.

“Alzheimer’s has been a tough and difficult field, really a graveyard of drug discovery,” says Ricks. “We have yet to produce a product. In that sense you could say, ‘What a disaster.’ But as in all science, learning and capability-building are incremental.”

In solanezumab’s first two Phase 3 trials, EXPEDITION (Effect of LY2062430 on the Progression of Alzheimer’s disease) 1 and 2, tested the drug in Alzheimer’s patients with mild to moderate disease, many of them possibly at a point when neuron loss was so profound no amount of amyloid plaque removal could likely improve function. But the latest Phase 3, EXPEDITION 3, will focus testing on early-stage patients, based on small improvements shown in an early-stage subset of the EXPEDITION 2 population. Amyloidtheory proponents already feel vindicated by those results, which they believe prove the concept. But of course, FDA approval of solanezumab would hinge on its final Phase 3 safety and efficacy data.

Meanwhile, Lilly Bio-Medicines is backing its bets on the early-stage anti-amyloid approach with additional research. It is working with an NIH-backed academic consortium on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study of people who are still asymptomatic even though their brains show evidence of amyloid accumulation.

Ricks compares the solanezumab situation with a more absolute case of failure in a Phase 3 trial of a cardiovascular drug, evacetrapib, for heart disease prevention in mid-2015. Evacetrapib also took a novel therapeutic approach with a higher than usual risk profile, though Phase 2 data was encouraging. But in Phase 3, although the drug appeared to reduce cholesterol — historically, a reliable biomarker — it did not seem to improve disease outcomes, and Lilly canceled the program. The lesson? Given the stillmysterious nature of the human body, and uncertainties in even the best science, reaching for a medical breakthrough requires taking a high risk.

“When you go into an innovative project, you must have a great deal of conviction that it is a good idea, and if it works, it can be a very significant asset for the company,” Ricks says. “A company of our size has to make those bets — not with the whole portfolio because then you put your sustainability at risk — but in challenging areas of science where, if the approach works, it makes a big difference. That is what we’re here to do, to solve bigger problems, and Alzheimer’s certainly fits into that category.”

Bio-Medicines is also fulfilling a commitment made in 2008 to return to immunology, as it develops a portfolio to treat chronic, disabling autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and psoriasis. Two late-stage assets lead the immunology pipeline: ixekizumab, which the business hopes to launch soon in psoriasis; and baricitinib for rheumatoid arthritis. A growing pipeline of early-to-midstage products looms behind the two leading candidates.

Bio-Medicines is also seeking to “leverage” its biotechnology capability in chronic-pain treatment, a sub-area of the neuroscience pipeline. It has two Phase 3 programs with monoclonal antibodies: a CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide) agonist, aimed at migraines and other serious headaches, and the nerve growth factor inhibitor, tanezumab, to treat joint and low-back pain. Medicines engineered to treat specific pain conditions may alleviate some of the pressure on opioid use for permanent-pain inflictions that remain intractable to any other treatment. But safety standards will be especially high for any new pain drugs, and the business will be plowing new ground in this area as well.

The Company Within

In many ways, Lilly Bio-Medicines follows an autonomous business model, making it and each of the other business units resemble a company inside a company. And for everything but the general and administrative functions shared by all or most other business units in the corporation and its collaboration with the global manufacturing and quality organizations, the unit operates independently. It has responsibility for all R&D and commercial activities for products in its portfolio.

Above all, says Ricks, each business unit has the highest responsibility for maintaining a direct “line of sight” to its customers, from development to market. Introducing the concept of “eye on the customer” in 2009, John Lechleiter was preparing the company for a recovery of growth despite the difficult times ahead — when patent expirations for major products would tend to separate the company from its customers.

Some of those customers have grown much larger, and a little testy, during the same period. Big payers and PBMs (pharmacy benefit managers) have brought de facto customer consolidation and clout to the pharma industry at last, and Lilly Bio-Medicines tries to meet them on common ground. “We very much think of the major U.S. payers as customers,” Ricks says. “That doesn’t mean we do everything they want, of course. There’s a tension there between capturing value for our shareholders and reward for the innovation we created, making sure the drugs that we invented to help patients actually get to the people who need them. The payers are the gateway to that goal, so we need to collaborate with them.”

Ricks says good customer relations depend on finding the overlap between the unique challenges each large customer has and the solutions Lilly offers. “It is the art of the possible. Payers are under a lot of pressure, too, but my personal view and philosophy is we all want to help people who are sick, so let’s start there and work together from that point.”

Ricks cites the company’s success in finding areas of common ground and “value points that both sides can live with” as helping it strike a couple of high-profile agreements with large insurers for “value-based pricing.” Under the agreements, Lilly indexes discounts to the performance of the drugs according to specific measures. “Moving to that kind of thinking creates a lot of opportunities for everybody to sit on the same side of the table. If the drug works, they pay for it; if it doesn’t, there’s a big discount, and that tends to waylay a lot of concerns about drug pricing and value.”

Valuable Traditions

To an outsider, it is easy to see Lilly throughout history as keeping its integrity and remaining durable while the world changed around it. Does it seem the same to an insider? Well, it does appear to come sincerely out of everyone’s mouth, in spontaneous ways.

“We do see ourselves as kind of a steady, Midwestern-grounded company, and we want to stick to what we know how to do — discover or partner and then develop important new medicines,” Ricks says. “There’s always a place for specific acquisition of a technology or a product, and we’ve done a fair amount of that, but corporate-level acquisitions that really change the nature of your company are so distracting in an innovative business where time and speed matter so much. We avoid those distractions, because innovation is the spring of our success.”

If the company’s Midwest center presents a challenge, it is the risk of isolation from the external forces and larger pharma/biopharma communities on opposite coasts. Yet, as Ricks maintains, the location may also encourage long-term thinking, a focus on execution, and coherent action. “And for a company that’s big, it keeps it small, too. Everyone who’s been here knows each other. You can move more quickly; it’s easier to communicate and get things aligned.” One cogent example of Ricks’ argument is his working ties with the heads of manufacturing and quality featured elsewhere in this feature: “Maria Crowe and Fionnuala Walsh are integral partners for me in everything from early development of particularly complex biologics to managing the commercial products. With all of the patent expirations, we must reduce the asset base of manufacturing technologies that are expiring while investing in the new asset base of technologies, years before the new products launch.”

See “Making Quality,” with Crowe and Walsh, to learn more about Lilly’s global manufacturing and quality organizations, which are also critically important to the diabetes business unit featured in the next section.

Still Insulin And Beyond

Like David Ricks and the other executives in this extended feature, Enrique Conterno has spent his career at Lilly, in his case, 24 years. He has had a multifunctional experience as he gained increasing responsibility at the company, with assignments in sales, finance, marketing, and business development. That included some time as head of sales and marketing in his home country, Peru, and Brazil, and as general manager of the company in Mexico. Also like Ricks, Conterno served for a time as president of Lilly USA. He became president of Lilly Diabetes in 2009.

“What’s exciting about this role is the ability to look at diabetes and lead the business from all types of perspectives, to integrate very different parts of the organization, from development to manufacturing to the worldwide globalization of our medicines,” Conterno says. “Before we created the business units, we were organized in functional silos, and all of our operations only came together at the level of the CEO.”

He says the company saw an opportunity to realign its “value chain” of operations around therapeutic categories, and he echoes Ricks in using the phrase spread by Lechleiter around the company: “We now have a better line of sight to our customers all across the organization. We are also able to operate today with much more agility in our decision making and execution, and that basic strategy is paying off for us.”

Functional Intersection

Conterno’s Diabetes unit has another thing in common with Bio-Medicines — the critical roles of manufacturing technology, infrastructure, and organization in its business growth. A joint governance committee is a built-in mechanism that regularly brings him together with Maria Crowe, head of global manufacturing, and Fionnuala Walsh, head of global quality, to share planning and decision making. Such collaboration has led to important insights about creating operational efficiencies, he says.

“Rather than thinking about our different products on a stand-alone basis, we needed to think about our insulin and technology platforms. Together, we developed ways of making our plants more flexible, and today our plants have the ability to manufacture any one of our insulin products. We also rethought how we make our insulin, and we decreased the number of steps in the process, consistent with our quest to decrease costs and become more competitive in the long term.”

Conterno emphasizes the need for both affordability and quality in the diabetes market, especially with the products needed for daily use of insulin. “An injector pen, whether disposable or reusable, has to work 100 percent of the time in the right way — meaning with every single dose it is important that it’s delivered with the appropriate accuracy.” As an independent business unit, he says, Lilly Diabetes can better judge its own performance in those areas against the competition, and it keeps another sharp eye on its competitors.

The improvements to Lilly’s insulin production also led to a large change in plans. As recently as 2014, the company intended to build a new, much larger plant to replace its existing facility in Indianapolis. But Conterno says the huge boost in efficiency brought on by truncating the insulin-making process and reworking plants to produce all insulin products made building any new plant unnecessary. Instead, the company did extensive remodeling within its existing footprint of insulin manufacturing facilities, doubling its output and lowering costs in the bargain.

“The new efficiency has allowed us to think a little more long term,” he says. “Now we have a capacity that can support the growing business.”

Close collaboration with manufacturing and quality has also aided the development side, where new products require careful formulation and process development, and later-stage candidates need production flexibility and support such as monitoring, dose-adjustments, and combination-therapy engineering. Based on research indicating synergistic benefits of some agents used together, several of the diabetes products in the pipeline are drug combinations.

Community Service

Lilly Diabetes has hosted a “diabetes bloggers summit” at the remodeled insulin plant in Indianapolis — just one of the ways it is taking pains to gauge patients’ gut feelings about the company’s leadership and responsiveness in the patient community. Conterno explains how patients came to play such a centerstage role for his business:

“From a historical perspective, our industry, in particular Lilly, has always been extremely focused on dealing with healthcare professionals, but in reality, patients now have access to much more information than they did even five years ago. So it has become critical for us to ensure we are significantly engaged with the diabetes community at large. To that end, we believe we have to engage both with the people who are huge advocates for us and also with our critics. By engaging in that way, sometimes we achieve a better understanding on both sides.”

“From a historical perspective, our industry, in particular Lilly, has always been extremely focused on dealing with healthcare professionals, but in reality, patients now have access to much more information than they did even five years ago. So it has become critical for us to ensure we are significantly engaged with the diabetes community at large. To that end, we believe we have to engage both with the people who are huge advocates for us and also with our critics. By engaging in that way, sometimes we achieve a better understanding on both sides.”

Going beyond the usual market research with patients for product development, the diabetes unit has ventured deeper into social media to reach its patient base. At the same time, adds Conterno, the business must be careful not to transgress legal barriers to anything that might be judged as marketing or sales of prescription drugs.

“People are willing to engage, and they’re really thirsty for more diabetes information, as long as the information is relevant to their needs, so we’re constantly exploring different avenues in which to engage,” he says.

Occasionally, as the web would have it, social media spill over into mass media. Conterno describes a serendipitous foray into the public realm — in a Super Bowl commercial. In the spot, NASCAR Xfinity driver Ryan Reed, a role model for Type 1 diabetes patients, re-enacts his previous win at Daytona this year to say, “You can do it all!,” then showcases a Lilly Diabetes information program for patients.

To patients, physicians, payers, and customers in general, Conterno says his business unit has listened carefully and responded with something more than selling. Many kinds of companies employ the metaphor of offering solutions, but when a business serves a patient base with chronic, daily needs for life-giving drugs and delivery devices, the solutions are real and material, not rhetorical. In Conterno’s case, you could argue it also gives him some bragging rights:

“We have the broadest portfolio of solutions in the industry. Now we’re launching new products, and our recently launched products are leading the market in the United States, Europe, and Japan. We are actually gaining market share with every Lilly product in every diabetes category. That’s quite unique given we have a mix of mature and newer products, but I attribute that to our innovation in creating solutions with our entire portfolio.”

Perhaps the solutions Lilly Diabetes offers, coupled with its competitive “affordability” strategy, will carry through the external pressure waves now hitting the entire industry, often in contradictory ways. “The public has questions about whether medicines are affordable enough, particularly in the U.S. market. But when I speak with analysts, typically their No. 1 concern is whether prices are deteriorating due to competition.”

With Humalog, the top diabetes product in the United States, the price has been essentially flat during the past five years, according to Conterno. On a net basis, list prices have not increased because payer rebates are significantly more consolidated today, a trend that will lead to financial challenges if it continues. Yet he remains sanguine. “We see significant pressures ahead, but they’re just part of the business, and why it’s so important that we look at ways to be more efficient on the marketing side or the manufacturing side, so we can make our medicines as affordable as possible.”

To see the same theme carried through and put into action on the manufacturing and quality sides, continue reading with “Making Quality.”

Making Quality

The following women lead two of the most critical organizations for Lilly’s growth and product development.

Maria Crowe has been with Lilly for nearly a lifetime. After graduating from Purdue in 1982 with a degree from the business school in industrial management and a computer science minor, she joined Lilly first in the IT area but then moved to manufacturing a few years later. She had two long international assignments, one in Puerto Rico and one in Ireland, where many of the company’s leading medicines were produced for the past 30 years. Thereafter, she had a variety of roles supporting multiple manufacturing plants, and in 2012, she took on the lead responsibility for global pharma manufacturing, which includes all of Lilly’s own manufacturing sites, as well as its contract manufacturing organizations.

Fionnuala Walsh joined Lilly in 1988, after earning her bachelor’s and doctoral degrees in chemistry from University College in Dublin, Ireland. She began at the manufacturing site in Kinsale, Ireland, working in technical services, project outsourcing, new-product introductions, and laboratory analytics. During the following years, she rose through positions of increasing responsibility for managing quality and manufacturing science and technology, becoming global quality leader in 2002, vice president for global quality operations in 2005, and head of global quality in 2007. Lilly Global Quality is a stand-alone organization with about 2,000 employees worldwide, monitoring, auditing, and ensuring adherence to regulatory and company quality standards all along the supply chain, including supply chain security and prevention of drug shortages. Its Lilly Quality System defines “quality requirements for processes throughout the product development cycle.”

What Essential Elements Of Lilly’s History Do You Believe Are Especially Relevant Today?

CROWE: Our manufacturing heritage in the company really goes all the way back to the very beginning, because Colonel Lilly instilled the principles of science and quality from the start, and the heritage has continued through the entire history of the company. In manufacturing, we make medicines, with safety first and quality always, and the patients should never have to question whether what they’re taking is right, because it’s our responsibility to ensure that it meets the highest quality standards in every case. As an example, insulin was discovered in Canada by Banting and Best, but they couldn’t figure out how to make insulin at commercial scale, and that’s where Lilly came in. So we helped them to develop a process that made high-quality insulin usable for millions of people.

WALSH: Our products can be sold in any market in the world based on quality. There was an old saying in a Lilly advertising campaign back in 1929, “If it bears the red lilly, it’s right.” I still like to think of it in that way. It means our product was designed right, it was made right, and it was sold in the right way. We put a lot of effort into the science of the products, and we also have a single quality system for the whole company. We are intentional about the standards we expect from our facilities, processes, analytical methods, educational programs, and everything else that affects product quality.

Big Pharma companies in general are not known for their forward-thinking, up-to-date manufacturing methods and quality, but Crowe says Lilly, in keeping with its traditions, develops and uses highly advanced technologies not only for its quality advantages but also for efficient coordination of its integrated resources.

What Would Be Some Good Examples Of Your Advanced Technologies?

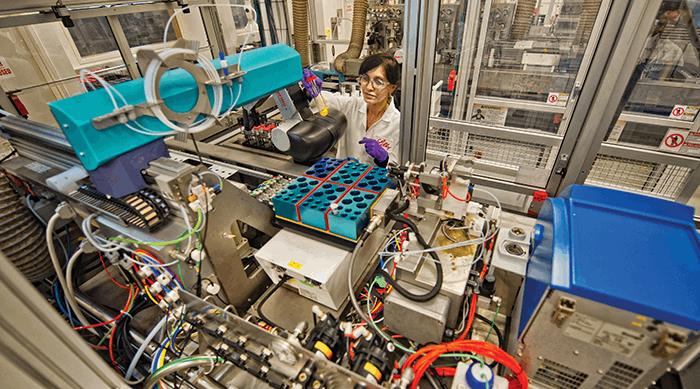

CROWE: If you came into our manufacturing sites, you would not see many people touching the product, because most of it is operated via electronic systems that are managed from a computer screen. As an example, our monoclonal antibody biologics is very sophisticated, and the equipment is set up to be extremely clean. Many visitors expect to see an old-fashioned scene with people along our production line, but our facilities look very different from that.

We also have a sophisticated set of IT solutions that all of our manufacturing plants share, so we can easily look at our data, aggregated or disaggregated, anywhere around the world. We benchmarked our IT a few years ago with an external consulting firm, which indicated our set of IT solutions was probably more sophisticated than any other company’s. Many companies have multiple versions of SAP running in different parts of their business, whereas we have one global solution, as an example.

WALSH: Our IT is unique, probably also because we’ve had the advantage that we haven’t merged with another company. In the major pharmaceutical firms that have merged many times, each acquired company brings its own culture and its own IT systems with it, and trying to integrate the different systems has been a considerable challenge. Being free of that challenge allows us to focus on innovation and come forth with a wonderful pipeline. We are now probably fighting above our weight in innovative products. If you’re spending all your energy trying to integrate new organizations, the focus gets diluted.

So Manufacturing And Related Systems Such As Information Technology Play A Key Role In Innovation?

CROWE: Yes. Manufacturing has played a key role in the scientific breakthroughs Lilly has made throughout history. But also, you can’t sell anything if you can’t supply it, so it is key that we have product available when we’re ready to sell it. That requires working with our development organization to collectively bring new products to patients faster — to reduce the cycle time from development to manufacturing to launch by creating a seamless approach among various related areas inside Lilly. That is game changing, as opposed to each component of the company looking at it from an independent standpoint.

Manufacturing and Quality play strong strategic roles in the company; Crowe and Walsh sit on the executive committee, involving them with R&D output, business strategies, and launch plans — and allowing them to coordinate with colleagues on how their organizations can support the overall mission of the company.

WALSH: When you are taking a product from development to manufacturing, you are really locking in up to 80 or 90 percent of your innovation at that point. In building a house, you can change the plumbing if the house is at the framing stage, but if it is all built and finished, changing the plumbing is a much more difficult and comprehensive affair. The intimate knowledge of a product that manufacturing and development share is essential to ensure the most efficient and effective use of our facilities, and that is truly game changing.

What Are Some Of The Ways You Are Strengthening Manufacturing And Quality In The Global Organization?

CROWE: We definitely are a global organization. In fact, more of our manufacturing sites and more of our manufacturing employees are outside of the United States than inside. However, we do have one strategic framework in which we operate. Our Operational Excellence Program defines the structure of each manufacturing site and the main ways we govern our operations for safety and quality. We also have a common set of metrics, monitored on a regular basis from each of our internal manufacturing sites and external contract manufacturers. It is a process replicated around the world that allows us to bring products to market faster, and to ensure we can supply all of the products as needed for the market. As we move people to different jobs and into different roles around the world, the system allows us to operate from a common framework.

WALSH: In some companies, quality is considered to be compliance alone, and compliance is extremely important to a very complex regulatory environment — brought about, I might add, by bad science or bad performance in the industry. But compliance is only part of the story at Lilly. The real story here is about the people who put real science and work into how they make the medicines. It’s not checking quality at the end of the line, although that is required — the most important part of quality is built into our everyday work and culture.

SIDEBAR: TRACKS OF GROWTH

Lilly’s Chairman, President, and CEO, John Lechleiter, discusses some of the main drivers he is counting on to keep the company on track to meet its promised performance goals in 2018. Lilly’s two largest businesses are Bio-Medicines and Diabetes, and Lechleiter highlights some of the outstanding new products they have launched and are developing:

Lilly’s Chairman, President, and CEO, John Lechleiter, discusses some of the main drivers he is counting on to keep the company on track to meet its promised performance goals in 2018. Lilly’s two largest businesses are Bio-Medicines and Diabetes, and Lechleiter highlights some of the outstanding new products they have launched and are developing:

“With our approvals last year, we now have in diabetes the most complete product lineup in the industry,” he says. “We have one or more molecules in every major class of diabetes medicines, which is unique, and of course partly due to the Boehringer Ingelheim partnership established five years ago. In Bio-Medicines, this year we will complete the transformation from psychiatric drugs, bone health, and men’s health into neurodegenerative disease, pain, and immunology. We are now launching Taltz (ixekizumab), our anti-IL17 antibody for treating psoriasis, which is a major event that marks the transformation of Bio-Medicines from a big primary care-focused business to a specialty-care business focused on those three main areas.”

In Alzheimer’s drug development at Lilly, most of the attention has gone to its anti-amyloid drugs solanezumab and a BACE inhibitor partnered with AstraZeneca (AZ). It also has a PEGbased antibody in Phase 1 that may have a different mechanism for eliminating amyloid from the body. Lechleiter also points to other Alzheimer’s approaches in the works. (See more in “Therapeutic Transformations,” with David Ricks, president of Lilly Bio-Medicines.)

“We’re not just focused on amyloid plaque, but we’re also looking at tau.” Lilly has a tau imaging agent in Phase 3 and has been investigating anti-tau drug candidates in early-stage research.

An up-and-coming growth driver, Lilly Oncology launched several new products in 2015 and may introduce as many as five others in the next five years. Two of the leading oncology molecules originated at ImClone, which Lilly acquired in 2008: Cyramza (ramucirumab), now approved for four different indications; and Portrazza (necitumumab), approved in 2015 for squamous cell lung cancer. A third Lilly oncology compound, olaratumab, is now under FDA review for treatment of soft tissue sarcoma. An immuno-oncology collaboration with AstraZeneca will test various combinations of AZ’s checkpoint blockers with Lilly’s pipeline of mainly pathway inhibitors and antigen-specific antibodies.

SIDEBAR: MIDDLE EARTH — PRESSURES FROM OUTSIDE

With confidence in the internal workings of his company, Lilly CEO John Lechleiter still engages with many forces beyond any company’s control, though perhaps not beyond its influence. Government policy and payer pushback, in that order, top his list of external pressures:

“I believe in policies that encourage investment and innovation — whether in pricing, taxes, or intellectual property protection. Those are critical to how we operate in the world, not just in the United States. We need to speak up and support policies that enable us to address some of the vexing medical problems that remain. Ultimately, the U.S. industry continues to be the world leader in generating new treatments and, in many cases, new cures. It is incumbent upon the leadership of the industry to ensure that we have a voice in the public debates over matters that directly determine whether we can continue to apply the wonderful science emerging in this field.”

Included in the same concerns is preserving the unique relationship the U.S. industry has with the government through the world-leading NIH. Lechleiter is optimistic about the long-term survival of the institution and grateful for a last-minute funding boost it received in the most recent budget. But he notes the downward budgeting trend in general:

“The NIH budget peaked in constant dollars around 2003. This industry depends on the basic research funding, that only the NIH can really provide, to enable us to understand biological pathways better and find new therapeutic targets.”

Payers have consolidated and comingled with pharmacy benefits managers, and some say they have grown into bullies who put patients and pharma companies at a financial disadvantage. Lechleiter expects other market forces to intervene.

“Third-party payers and PBMs (pharmacy benefit managers) don’t exist in a vacuum, and ultimately, for commercial plans, by and large employers determine what the benefits must be, and there are limits to what they would deny their employees. The voice of consumers still shines through here; there are no smarter or better-informed consumers in the world than American consumers. I don’t believe that somehow they will be disintermediated by a third party.”