Most U.S. Pharmas Ignore Cuba, Despite Relaxed Rules

By Gail Dutton, Contributing Writer

Follow Me On Twitter @GailLdutton

The Cuba trade embargo has almost ended, but American pharmaceutical companies have barely noticed. In a quick survey I did of 13 pharmaceutical companies ranging from Big Pharma to small generics manufacturers, plus two industry associations, all 15 organizations declined to comment about Cuba’s potential role in their business strategies or opportunities and challenges involved with doing business with that nation. Only one of those claimed the silence stemmed from competitive interests.

Two American organizations, however, are going on the record to discuss their work with Cuban researchers and their efforts to bring innovative research involving cancer vaccines and levels of consciousness (e.g., comas, brain death) to American patients.

IN-LICENSING A NOVEL CANCER VACCINE

In late October, Roswell Park Cancer Institute became the first American organization to receive FDA approval to launch a clinical trial treating American patients with a Cuban-made therapy.

Roswell Park’s upcoming Phase 1 trial will test CIMAvax-EGF, a lung cancer vaccine that is both developed and manufactured in Cuba and has been administered to thousands of patients globally. “This vaccine is based on an antibody-based strategy designed for mass production. It’s a completely novel vaccine approach that we haven’t seen in the U.S.,” says Thomas Schwaab, M.D., Ph.D., who is chief of strategy, business development, and outreach at Roswell Park.

Approval to begin trials came soon after the FDA inspected the Cuban vaccine manufacturing facility. Cuban life sciences facilities are accustomed to meeting international requirements, Schwaab says. For instance, “Japan’s Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), widely considered the strictest of regulators, also has approved Cuba’s vaccine manufacturing facilities.”

To further development of CIMAvax and other biotech products, the U.S. Treasury Department also authorized Roswell Park to form a joint venture with Cuba’s Center of Molecular Immunology (CIM) for product research, development, manufacturing, and marketing.

THOMAS SCHWAAB, M.D., PH.D. Chief of Strategy, Business Development, and Outreach Roswell Park Cancer Institute

The groundwork for these collaborations began about three years ago under the Cuba trade embargo when Roswell Park obtained a license from the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) to exchange scientific material and information with Cuba. Specifically, Schwaab elaborates, “The license allowed us to conduct basic research and Phase 1 clinical trials for a limited set of drugs that includes CIMAvax and some preclinical development candidates.” The business relationship was fast-tracked in early 2015 when Roswell Park leaders participated in New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s trade mission to Cuba.

“We had to move mountains to get CIMAvax to U.S. patients,” Schwaab recalls. Obtaining an OFAC license, State Department permits, and FDA inspection are not trivial endeavors. “Throughout it all, the Cubans have been incredibly cooperative and professional.”

EVEN EXEMPTED EXCHANGES TAKE TIME

BioQuark isn’t as far along as Roswell Park, despite starting earlier. It has worked with an OFAC attorney for the past four years to formalize relations with Cuba’s Calixto Machado, M.D., an internationally recognized expert in the niche specialty of brain death and disorders of consciousness.

“Our relationship with Dr. Machado is governed by the OFAC’s exempted informational materials exchange regulations,” says Ira Pastor, BioQuark CEO. “Dr. Machado has a five-year visa to lecture throughout the U.S., so we are allowed to talk with him but not to share proprietary technology or to compensate him.” Recent changes to U.S. rulings specific to Cuba may change those stipulations.

BioQuark wants to apply Machado’s insights into brain death to BioQuark’s studies of epimorphic regeneration in humans, for example, restoring function to the central nervous system or regrowing damaged organs. “There’s not a lot of research on brain death, so conversations with Dr. Machado have been invaluable,” Pastor says. “We’d like to become more involved with him, either through a consulting arrangement in the U.S. or through joint research in Cuba.”

As the U.S. trade embargo against Cuba gradually relaxes, bureaucratic hurdles remain. “We still need to obtain permits from the OFAC and State Department,” Pastor says, as well as comply with Cuba’s research regulations. “This area requires extensive legal expense and consultation.”

CHANGES EXPAND U.S. OPTIONS IN CUBA

The new, more open relationship with Cuba is in its early days, and regulations are in flux, so it’s no wonder American companies hesitate to formulate strategies involving the communist nation. One of the most recent revisions to the embargo took effect Oct. 17, when the U.S. departments of Treasury and Commerce amended section 515.547 of the Cuban Assets Control Regulations.

The changes allow Cuban companies, and American companies working with Cuba, to seek FDA approval for drugs originating in Cuba. They also enable a range of collaborations and partnerships at all levels of research and development from discovery to postmarketing and importation. Furthermore, the changes allow Cuban nationals to conduct research in the United States and permit American organizations to award grants and scholarships for scientific research to Cuban nationals. (Educational and humanitarian grants and scholarships already were permitted.)

“I don’t expect Cuban companies to apply to the FDA directly,” says John Caulfield, consultant on business in Latin America and head of the U.S. Interests Section (now Embassy) in Cuba until his retirement in 2014. “They probably would have experienced partners that would in-license rights to products.”

In Roswell Park’s case, “The October amendments to the Cuban Assets Control regulations haven’t affected our work. Our specific OFAC license allowed us to do many of those things that now are feasible under a general license,” Schwaab says.

The changes, however, will make it easier to expand projects and to incorporate new research findings. “The license we have is very specific,” he continues. “Before the new regulations took effect, we would have had to apply for a new license to incorporate new research developments. Now we can move forward easily. Easing the licensing requirements accelerates research.”

It’s important to recognize that only certain regulations regarding Cuba have been relaxed.

Other regulations remain intact. Therefore, for example, the Bureau of Industry and Security within the U.S. Commerce Department still requires special licenses to export high-tech goods or equipment to Cuba or to import Cuban materials into the United States. General tourism remains prohibited, so travelers to Cuba must comply with OFAC’s general license for travel.

OPENING CHINA WAS DIFFERENT

It’s natural to assume that entering Cuba commercially is similar to entering China in the mid-1990s. For instance, “Cubans are extremely capable scientists who are very proud of their country and culture. It’s very important to them to deal with those with whom they have a personal relationship and trust,” Schwaab says.

So, one of the biggest challenges of doing business in Cuba is to build strong personal relationships with business partners. Forming those connections has become easier since Cuba removed travel restrictions on its citizens in 2013. Now scientists can travel freely to international meetings, some of which are hosted in Havana, and meet potential business partners.

More often, however, Cuba and China are more dissimilar than alike, Caulfield says. For instance, “When the U.S. entered China, we were looking to sell things to a very large market. That’s not the case with Cuba. With a population of 11 million people, it doesn’t have a large market.” Cuba, therefore, requires a different strategy.

Although Cuba and China both are communist, the execution of that philosophy is very different. China, for example, incorporates capitalism into its business model, while in Cuba, all businesses are owned by the state. Therefore, all negotiations, whether to in-license a product from Cuba or export a product to that island nation, are conducted with government officials. “The people actually doing the negotiations won’t have the final say,” Caulfield explains. “That must come from a government minister or from the Council of Ministers. That’s very different from dealing with other companies throughout the world.”

Schwaab, however, characterizes the chain of command differently. “We are negotiating with employees at the CIMAB – the commercial arm of the CIM. They have final authority to make decisions but may need approval from a board of directors.”

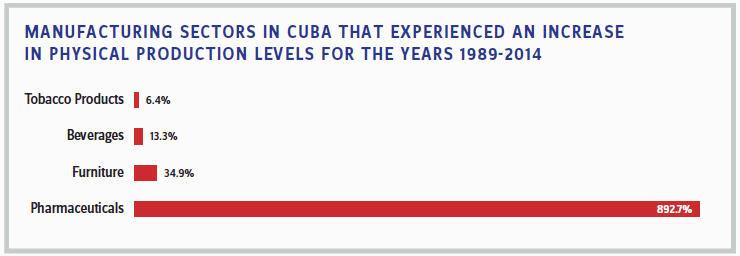

Cuba’s relatively small market, limited buying power, and complicated business environment have contributed to the implosion of its manufacturing base. Between 1989 and 2014, its manufacturing output fell more than 45 percent.

Pharmaceutical manufacturing is one of the few areas with positive growth. It increased 892 percent during that time frame because of the Cuban government’s interest in building its genetic engineering prowess (at the expense of other sciences), according to The CubanEconomy.com. Since Cuba has staked its future on its biotech industry, it recognizes the importance of secure intellectual property rights. The Chinese, in the 1990s, did not.

KNOW BEFORE YOU GO

“Everything involving Cuba is a little different than in the rest of the world,” Caulfield notes. Those in charge of its businesses aren’t as informed about pharmaceutical validation, financial requirements, and financial terms as their counterparts internationally. Therefore, American companies attempting to bring a Cuban drug to the U.S. market must anticipate a learning curve for all parties.

Companies can shorten the education process by hiring an OFAC attorney early in the development of any potential strategy involving Cuba to help understand what’s possible, what’s impossible, and the time frame to accomplish anything. But as Pastor says, no matter who you have helping you, “nothing occurs overnight.”

English speakers are rare among the populace. Although the island was a U.S. protectorate and American companies flourished until they were nationalized in 1960, the English language is less prevalent than in other nations. After the revolution ended in 1959, schools began teaching Russian rather than English. Although that has changed, “For business, take a translator,” Caulfield advises.

![]()

"Everything involving Cuba is a little different than in the rest of the world."

JOHN CAULFIELD

Consultant On Business In Latin America

Cuba isn’t frozen in time. Visitors to Cuba typically return talking about the classic 1950s-era cars that still are being driven, but “there are plenty of Toyotas and Hyundais on the streets,” says Marc Hoffman, M.D., chief medical officer for the clinical trial patient-matching service Patient identification Platform, who toured the island last August. It is, nonetheless, a very poor country. The highest earners in the country still gross little more than $1,000 annually, and most are closer to $500. Its gross domestic product (GDP) is $77.15 billion at the official exchange rate.

Despite this poverty, there are opportunities in Cuba, mainly in the form of in-licensing Cuban therapeutics. Regulations are still in flux but are gradually normalizing. If American life sciences companies decide Cuban options are worth investigating, patience will be a necessary virtue.