Move Over ADCs: Nanoparticle-Drug Conjugates Are Joining The Cancer Fight

By Louis Garguilo, Chief Editor, Outsourced Pharma

Just when we were feeling comfortable in our understanding of the science and technologies behind ADCs – drugs linked to antibodies that target tumor cells – we need to plunge into the next advancement in this cancer-fighting realm. Cerulean Pharma (NASDAQ: CERU) President and CEO, Chris Guiffre, at his office within the AstraZeneca BioHub in Waltham, MA, assures me it’ll be well worth the dive.

Cerulean’s been at this new form of anti-cancer drug development and delivery since 2006. The journey has been anything but straight-line. To help us better understand it all, we’re also joined by the inventor of Cerulean’s lead drug, and what Cerulean calls this new category of cancer treatment: nanoparticle-drug conjugates (NDCs). Mark Davis, Ph.D., is professor of Chemical Engineering at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Davis is in an elite group of individuals who are members of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the National Academy of Medicine. “A rare triple threat,” as Guiffre calls him.

According to both men, NDCs are an evolution of ADCs (antibody-drug conjugates) and a refinement of “old-fashioned nanotechnology.” Specifically, Cerulean’s goal is to create a cancer treatment that’s more efficient, effective, and better tolerated by patients, and thus more humane. (For Davis, this is a personal matter, documented in the sidebar.)

After paddling through some rough waters (described below), Cerulean raised capital via an IPO in the spring of 2014. It’s now re-advancing its lead compound — CRLX101 — through a Phase 2 clinical trial soon to wrap up. A subsequent Phase 3 trial could get underway early next year. The company also has follow-on compounds in the clinic. It’s developed a platform technology for future biopharma partnerships to create more NDCs. The overall business plan is, of course, contingent upon further progress in the clinic, but if that happens, Cerulean might just propel us into an era of the independent, commercially successful nanopharmaceutical company.

But first … that science and technology dive.

NANOTECHNOLOGY FLOWS FROM THE SHORES OF ADCs

Guiffre, in his current role as chief executive since March of last year, says that Cerulean created the NDC moniker. “We gave some thought to trademarking the term,” he says, “but decided the real value is in it being used to describe a new class of drugs that are a next-generation nanopharmaceutical. We’re determined to see it used even more than ADCs some day.”

Regarding those ADCs, Guiffre draws us back about a decade, “when people were raising an eyebrow at the technology, and wondering why Seattle Genetics and Immunogen [leaders in this field] hadn’t given up.” Instead, they and others started delivering on the promise of targeting tumors and sparing healthy tissue in cancer treatment. Two ADCs are currently marketed: Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris; Seattle Genetics and Millennium/Takeda) and Trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla; Immunogen and Genentech/ Roche). Many companies have entered the field in the past few years, including Big Pharmas, such as Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi. (In previous issues I’ve also written about nano-specialists such as Nanobiotix, Sonrgy, and Cour.)

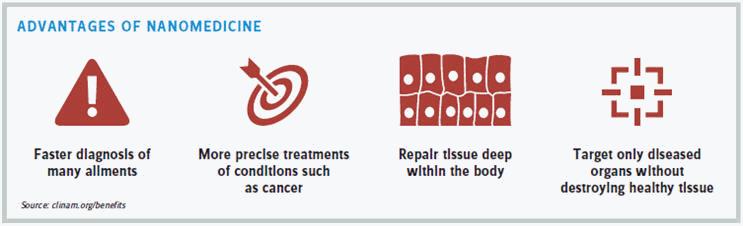

The fundamental difference between Cerulean’s NDCs and their biology-based predecessors is the replacing of antibodies (biology; living organisms) with particles (nanotechnology; fabricated and shaped organic material) to deliver cancer agents directly to tumors. This alteration of science and material actually allows for the release of highly toxic anti-cancer drugs within a tumor: more potent medicine delivered more safely.

Cerulean’s NDCs also improve on other nanotechnologies. Guiffre boils it down for us. “First, due to our nanoparticle ‘backbone,’ our NDCs remain stable in the bloodstream. They are small enough to slip through the large pores in solid tumor vasculature, but large enough so they don’t slip through the small pores in healthy vasculature. Based on our conjugation, they penetrate the tumor tissue until taken up inside the tumor cells, through a process called macropinocytosis. Only then is the drug slowly released, thanks to our linker technology. You can see the advantages of both nanotechnologies and ADCs at work here.”

SHAPE AND SIZE MATTER

In what professor Davis describes as a world’s first, he and his colleagues published a paper earlier this year in PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America) describing a clinical trial of nine patients demonstrating that nanoparticles in human beings do concentrate in tumors and spare adjacent, healthy tissue. “It works as advertised,” says Davis.

What “worked” was Cerulean’s lead compound, CRLX101. It’s an NDC with a payload of camptothecin, a potent chemotherapy discontinued in clinical development in the 1970s because it was too toxic for patients to handle. (There are other camptothecin-class drugs on the market, including irinotecan and topotecan.) By linking camptothecin to the nanoparticle payload, Davis invented a new chemical entity (NCE).

CRLX101’s lead indication is relapsed renal cell carcinoma: kidney cancer. The FDA granted CRLX101 fast track designation in combination with Avastin (bevacizumab) for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma following progression through two or three prior lines of therapy. CRLX101’s second indication is platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. The FDA granted CRLX101 orphan-drug designation in this indication.

Why CRLX101 worked is a matter of shape and size. “I’ve been preaching for a long time for ‘well-designed nanoparticles,’” says Davis. He explains that most nanoparticles today don’t possess the requisite properties, including the most fundamental attribute of size. Many Life Science Leader readers will know the nano field was defined when it became possible to bring particle size down to the magic number of 100 nanometers. Not good enough, says Davis. “We kept saying 100 nanometers is way too large if you actually want particles to penetrate and access the larger part of the tumor. Cerulean’s particles are much smaller, in a range of 30 nanometers, and much better designed. That’s being verified now.”

Finally, Guiffre brings up the component in drug conjugation that has differentiated, limited, frustrated, and at times otherwise defined the ADC platform from its beginning: the “linker” technology. More precisely, how do you stably “link” a toxic anti-cancer agent to an antibody so that the agent is not released anywhere but at the site of the tumor? As this combining (or conjugation) of payload, linker, and antibody continues to evolve on the ADC side, nanotechnology may be jumping ahead with better options. Guiffre says Cerulean has become adept at nano-linker technology.

“We now have clinical data showing DNA damage in ovarian cancer patients almost a week after a single dose of CRLX101,” Guiffre says. “That’s really quite remarkable to have that kind of an effect.”

"We kept saying 100 nanometers is way too large if you actually want particles to penetrate and access the larger part of the tumor. Cerulean’s particles are much smaller."

"We kept saying 100 nanometers is way too large if you actually want particles to penetrate and access the larger part of the tumor. Cerulean’s particles are much smaller."

Mark Davis, PhD.

Professor of Chemical Engineering, Caltech

COMING UP FOR AIR

Some of that success was arrived at via an unsuccessful clinical trial. It was in 2013, some seven years after the founding of Cerulean by Alan Crane, the company’s first CEO and a partner in Boston-based healthcare firm, Polaris Ventures. CRLX101 failed to reach its endpoint in an initial Phase 2 clinical study in nonsmall cell lung cancer, throwing the company into a flurry of notoriety and adversity.

The trial brought with it some lessons learned the hard way. “That failure in the clinic really had nothing to do with the drug itself,” says Guiffre. “It had everything to do with our having poorly designed the study, which we then had conducted in Russia and Ukraine. With the benefit of hindsight, that trial was doomed to failure from the beginning.”

Davis and Guiffre, though, point to the ray of enlightenment emanating from that experience. They say in retrospect this was the first randomized study where a large number of patients showed that CRLX101 had similar overall survival, progression-free survival, and overall response rate to FDA-approved cancer drugs in second and third line nonsmall cell lung cancer. “Maybe even more importantly,” says Guiffre, “we delivered a highly-toxic drug into 100 cancer patients, and it was remarkably well-tolerated.”

Have others — potential investors perhaps — drawn those same positive conclusions from this first defeat in the clinic? “Well,” replies Guiffre, “you normally don’t write stories about companies that go public with a successful IPO 13 months after having such a failure in a randomized trial. But part of why we are here now is because that trial proved our NDC did what it was supposed to do.”

TARGETING CERULEAN’S FUTURE

Four years later, Cerulean’s back in the clinic with CRLX101. A second NDC in the Cerulean pipeline, CRLX301, will most likely have started its Phase 2 trial by the time you read this. Cerulean has also developed a full-blown NDC-creating technology, called Dynamic Tumor Targeting Platform. (This time Guiffre has decided to trademark.) The company is banking on this technology to bring in partners and collaborators from the biopharma industry. Guiffre calls these “platform deals.” He explains, “This is similar to what Seattle Genetics and Immunogen have done in their ADC history. It took them some time to attract partners. Now it seems like every big biopharmaceutical company is working with one of those two groundbreaking ADC companies. I think Cerulean is at that point. We’ve proven our technology, and it’s realistic to think we’ll engage in these strategic collaborations.”

"We now have clinical data showing DNA damage in ovarian cancer patients almost a week after a single dose of CRLX101. That’s really quite remarkable to have that kind of an effect."

"We now have clinical data showing DNA damage in ovarian cancer patients almost a week after a single dose of CRLX101. That’s really quite remarkable to have that kind of an effect."

Chris Guiffre

President and CEO, Cerulean Pharma

We’ll have to wait to see if that enthusiasm, and grand comparison, pans out. As Guiffre indicates, there’s nothing unusual about a technology platform, and, in fact, besides in the area of ADCs, contract research and development organizations of various stripes are employing it to gain customers and partners. In Cerulean’s case, a drug company would come to them with a potential anti-cancer drug (the NDC payload) with significant activity, but as is too often the case, also with concerns about the therapeutic index (i.e., efficacy versus toxicity). Cerulean could potentially engineer the compound into an NDC for the partner to then take into the clinic. One can envision various revenue models for this beyond pay-for-service, including Cerulean taking a stake in the future success of molecules, milestone payments, and additional technology development. All of these (and more) have been put together on the ADC side.

A second partnership, or contract-service strategy for Cerulean — again not entirely untried — has to do with patent expansion. Guiffre believes his NDC platform will allow biopharmaceutical companies to launch improved products to replace those about to go off patent. “The successor product would become an enhanced NDC, with the original product as its payload, making it safer and more effective, and adding IP,” he explains. “Doctors are already familiar with the original product. Now they can offer patients a better version that’s more active and better tolerated. I ultimately think that’s the strategy that will pay significant dividends for us, our partners, and for patients.”

NO SMALL PLANS FOR THE FUTURE

The final part of our dive — although accompanied by remaining waves of assumption — is into the future. What’s the ultimate game plan for Cerulean should CRLX101 (or other NDCs) gain FDA-approval to treat one or more forms of cancer? Will Cerulean out-license to an established Pharma (or Bio)? Will it opt to become one of the first nano-versions of commercial biotechs?

“If you think of the well-known example of Abraxis, a nanotech company that was acquired by Celgene for about $3 billion, they were on their way to becoming a very successful independent nanotech before they were acquired,” says Guiffre. “That certainly is one path that can’t be ruled out.” Again, we’ll credit Guiffre for an expansive and enthusiastic comparison. Yet, somehow I sense even this bright scenario might not be his first choice. In fact, after a pause, he adds another colossal comparison: “However, if we were to launch our products and commercialize them ourselves in the U.S. — as we did when I was at Cubist — could we grow to become the next Biogen or Genzyme in Boston? I hope so. If that happens, I think you may point to us as the first commercial biopharmaceutical company grown entirely on nanotechnology.”

As someone who’s been following this integration of nanotechnology with drug discovery and development, that would be a grand accomplishment. And I think Guiffre would agree; it never could have been achieved without a great assist from the biopharma pioneers who first brought us, and continue, the science and technology of ADCs.

WHEN NANOMEDICINE GOT PERSONAL

by Louis Garguilo

Documenting everything Mark Davis is and does professionally takes more than a few nano-seconds. Among other things, he’s the Warren and Katharine Schlinger professor of Chemical Engineering at the California Institute of Technology and a member of the Comprehensive Cancer Center at the City of Hope and the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center at UCLA. He was the first engineer to win the National Science Foundation Alan T. Waterman Award. He’s been elected into the National Academy of Engineering, the National Academy of Sciences, and the National Academy of Medicine.

Most important to us, though, is something personal for Davis: his strong desire to develop a nanopharmaceutical that better targets tumors and thus alleviates the suffering cancer patients encounter with current treatments.

Davis’ wife, Mary, was diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 36 in April 1995. Thankfully, she is a cancer survivor. Davis has written about that time. “By Valentine’s Day, Mary had lost all her hair for the second time. She was unable to eat, was constantly vomiting or felt nauseous, and was given nutrition by IV. She had completely lost her immune system and was in isolation for three weeks.” During that isolation, Mary said to Davis: “There’s got to be a better way … the treatments are making me sick. Treatments should make you feel better.” When he replied this was not his field of expertise, she retorted: “You people at Caltech are smart, go work on it.”

As we were starting our discussion for our main article on Cerulean, company president and CEO, Chris Guiffre, was adamant that I first understand this dimension that Davis brings to the company. As per that article, Cerulean is attempting to commercialize the drug and nanotechnology developed by Davis to fight cancer. “Mark is a brilliant scientist, and this has been his motivation inspiring his nano inventions in the field of cancer. He decided to invest decades of his life to get to where we are now.”

Davis and Cerulean are winding up a Phase 2 clinical trial, with more planned and backup compounds also in the clinic. Professor Davis’ nanoparticle-drug conjugates (NDCs) are, according to Guiffre and Davis, the next step in an evolution of “old-fashioned nanotechnology” applied to the theory of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), which themselves have been exciting developments in the fight against cancer and specifically better patient experiences during the battle.

Technology For A Humane Cancer Treatment

Here’s a bit more detail on the technology Davis and Cerulean are developing, particularly the fundamental attributes — and differences — between ADCs and their NDCs:

- With ADCs, a cytotoxin (anti-cancer agent) is linked to a monoclonal antibody that seeks out and attaches to tumors via overexpressed receptors on the surface of the cancer cells. In theory, the cytotoxin is then released. Unfortunately, during the course of treatment, the state of overexpressed receptors can disappear. There remain limitations on how much cytotoxin (and which ones) can be successfully linked to a certain antibody, and although ADCs help spare healthy tissue by targeting tumors, overall ADC stability and release of the cytotoxin remains problematic.

- With NDCs, a cytotoxin is linked to a nanoparticle, which in the case of Cerulean’s technology, actually enters tumors by taking advantage of EPR – enhanced permeability and retention effect. Moreover, once inside – in a process called macropinocytosis – the tumors actively engulf the NDCs. “It’s almost as if the tumor consumes the NDC as food,” Guiffre says, except of course this food is lethal.

Getting Closer

The drug and technology Cerulean in-licensed from professor Davis, known as CRLX101, has, to date, been tested in more than 350 patients, as both monotherapy and in combination with other cancer treatments. At this writing, we know from multiple clinical trials that CRLX101 is encouragingly active as both monotherapy and those combinations of treatment. Of great personal importance to Davis – and cancer patients – is the drug is well tolerated, and spares healthy tissue.

“I would never have done this without having seen what Mary went through,” says Davis.

And according to Guiffre, everyone at Cerulean has taken up his personal goal and Mary’s challenge. There will be no lack of motivation to keep moving forward at Cerulean.