Novavax: Scouting Past The Long Trail To Market

By Wayne Koberstein, Executive Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @WayneKoberstein

The Enterprisers: Life Science Leadership In Action

PRESS-TIME THUNDER

Based on long-term discussions with Novavax, as well as close observations over several years, this article had been completed when, suddenly, a clinical lightning bolt struck the company. Novavax announced results of its Phase 3 RSV F vaccine trial for older adults that were far worse than the most pessimistic forecasts before the announcement. The trial failed to show efficacy in either the primary endpoint, prevention of moderate-severe RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease, or the secondary endpoint, reducing the incidence of all symptomatic respiratory disease due to RSV. In perhaps the most dramatic demonstration of the trial failure, the company itself voiced surprise and disappointment at the results, possibly the worst for any vaccine in history. Obviously, the failure calls to question the basic focus and platform of the company and also the central premise of this article — that there is more to the company than this one trial. In fact, this single trial may be damaging enough to determine the fate of Novavax as a business entity — one I still believe has shown remarkable enterprise in a field even tougher than it imagined. The results will also make many of the hopeful plans and positions stated in this article ring hollow, or, at the least, poignant. It is humbling to admit that one day’s event can indeed bring a different end (or turn?) to a long journey. Thus, we present the article here mostly as it was before the Phase 3 announcement, leaving its entrepreneurial narrative in the hard, but real, context of the press-time news.

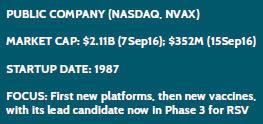

Clinical challenges lurk all along the pathway for any company developing new vaccine candidates and technology — and that goes at least twice for Novavax. As we go to press with this, the company is dealing with an anxious investment community about the “failed” Phase 3 trial of its RSV F vaccine in older adults, for protection against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). (See “Press-Time Thunder.”) To outside observers, the trial’s outcome may seem only binary, make or break. But for those who work inside Novavax or study it in greater depth, the picture is much larger and the story much richer. It is bound to be, for the company has taken an especially long and winding path, hopefully the path to innovative vaccines.

This is not the first time The Enterprisers has featured a vaccine developer (see the most recent, Codagenix, November 2015). The vaccine field is tough enough to require extraordinarily creative and tenacious enterprise by any company that enters it. Foresight — the ability to look all the way down the path and adjust development plans for the vagaries of the commercial environment — is particularly essential.

Novavax started up in Sweden almost 30 years ago, and since then it has gone through a series of corporate makeovers and temporary setbacks, punctuating general advancement in building new vaccine platforms and agents. In 2014, I met the president and CEO, Stan Erck, who covered the basics of the company, its technology, and its products in development. And when I spoke recently with John Trizzino, SVP of commercial operations, the conversation actually picked up where the previous one with Erck had left off — how Novavax has gone to exceptional lengths to study the potential commercial environment far in advance of launching its first product.

Novavax started up in Sweden almost 30 years ago, and since then it has gone through a series of corporate makeovers and temporary setbacks, punctuating general advancement in building new vaccine platforms and agents. In 2014, I met the president and CEO, Stan Erck, who covered the basics of the company, its technology, and its products in development. And when I spoke recently with John Trizzino, SVP of commercial operations, the conversation actually picked up where the previous one with Erck had left off — how Novavax has gone to exceptional lengths to study the potential commercial environment far in advance of launching its first product.

Significantly, Trizzino is not a marketing officer in the conventional sense, having no products to market yet. His title reflects an important, but too-often overlooked, function in entrepreneurial drug development — one that collects and imports knowledge about prospective practice settings, reimbursement factors, competitive forces, and other conditions its products are likely to face in the market and on the way to it. Such knowledge drives the company’s decision making in multiple areas of R&D, from selecting target indications to designing trials. It also guides a progressive refinement of the company’s entire business model in support of its development strategies.

LONG ROAD TOWARD LAUNCH

For its lead product, the RSV vaccine, Novavax is seeking indications covering the three most vulnerable patient groups: over-60 adults, infants, and children six months to five years in age. Mothers receive the vaccine before birth to confer protection on infants. The vaccine is designed to block the fusion (F) protein on RSV, as does the only marketed treatment for RSV infection, the monoclonal antibody palivizumab (Synagis) from MedImmune. Novavax uses its own “recombinant protein nanoparticle” technology to produce a potentially higher-potency, more deliverable vaccine against the same target. No other RSV vaccine is approved, or likely to be soon.

Like other innovative vaccine developers, Novavax has created its own non-egg production technology to manufacture its products. It has engineered an insect cell line to make rDNA-produced nanoparticles and virus-like proteins (VLPs) that mimic the surface proteins on living human cells. “The particles we make are folded like natural viral proteins and are highly immunogenic,” Erck told me. “Greater potency means greater shipping and storage efficiency,” he added.

The distribution advantages and speed of production of the Novavax technology especially appealed to BARDA (Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority) back in 2011, when it awarded the company a contract worth up to $179 million for development of recombinant seasonal and pandemic flu vaccines. Moreover, prevention always beats treatment, of course — medically, logistically, and financially

In recent years, the company shifted its primary focus from flu to RSV, and it replaced its VLP-based flu vaccine with a nanoparticle candidate. “The RSV program has accelerated quickly, and our new nanoparticle flu vaccine candidate is the result of many lessons learned over the years about the benefits of this nanoparticle technology, as well as what we’ve learned from our RSV program development,” says Trizzino. Based on such knowledge, Novavax will ultimately fold the reformulated flu vaccine into a combination flu/RSV candidate slated for the start of a Phase 1 trial this fall.

Trizzino explains that the pairing of RSV and flu vaccines is hardly random; both viruses produce lower respiratory tract infections that are often confused and misdiagnosed because they have similar symptoms and occur in the same fall-to-spring time frame. Reformulating the flu component ensured both parts of the combo vaccine conform to the nanoparticle modality. “The formulation is naturally a better fit than if we took two completely different technologies and tried to co-formulate,” he says.

The RSV F vaccine will launch first, however, according to current company plans — and hopes. Data from the Phase 3 “Resolve” trial in over-60 adults is due soon. RSV infection can cause a wide range of symptoms, in some cases mild, but in others severe to fatal. It is particularly dangerous to children under two years old, for whom it is the biggest cause of hospitalization. Trizzino says it kills 200,000 children globally every year, mainly in low-resource countries, and the Gates Foundation, a Novavax funder, is determined to help develop an RSV vaccine to protect those populations.

In 2015, the foundation awarded the company a grant worth up to $89 million to support the Phase 3 trial and regulatory filings for the vaccine in pregnant women. Under the grant terms, in exchange for World Health Organization (WHO) prequalification, Novavax agreed to make the vaccine “affordable and accessible to people in the developing world.” It has a development agreement with the global health group PATH, (formerly the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health), from which it will receive about $7 million for RSV vaccine trials in low-income countries.

Novavax is also preparing for future business outside North America and Europe through CPL Biologics (CPLB), which is its joint venture with Cadila Pharmaceuticals of India, and a licensing deal with LG Life Sciences of South Korea. In Europe, the company still has its facility in Uppsala, Sweden. It also has candidates in development for Ebola and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).

The company is not alone in pursuing RSV, of course; almost every vaccine developer of every size has an RSV program, though just a handful are in human trials. The Novavax candidate has been the leader in the field, and it is the only vaccine to block the same domain on the fusion protein as does Synagis, which may be the strongest possible validation of its target at this point. The nearest competitor candidate is GSK’s recombinant vaccine, now in Phase 2.

Erck told me more about why the correspondence of the RSV vaccine with Synagis is important: “Our vaccine effectively turns people into living Synagis factories, invoking the same antibodies. MedImmune did us a great service over the past decade or so by discovering the minimum level of antibodies required on a dose-per-weight basis. We found that, when we vaccinate healthy adults, we stimulate a level of antibodies tenfold greater than the minimum level — a very powerful antibody response.”

Some journalists and analysts have applied the word “disappointing” to results from the Novavax RSV Phase 2 trial in pregnant women, announced in September 2015, which has clouded the picture somewhat. The trial data showed the vaccine induces antibodies to RSV in the mothers but did not demonstrate the pre-birth, maternal inoculation passing the antibodies to the infants. Still, in the company’s and its partners’ view, the results were positive enough to support proof of principle and inform the Phase 3 trial design.

The Novavax strategy drives a stake in the ground — applying a novel platform it has taken decades to develop in formerly unexplored ways. “No one has ever put an RSV vaccine and a flu vaccine together in a combination,” Trizzino says. “Some companies have taken a run at RSV vaccines and failed, but no other company has been able to demonstrate efficacy for an RSV vaccine as we have in our Phase 2 trial, and now we will take another novel step in moving into a combination flu/RSV vaccine.”

MARKET VISION

Few precommercial companies have a “commercial readiness” program anywhere near the scale of the one at Novavax. Trizzino speaks about the meaning of the term and purpose of the program: “Stan Erck had a vision and knew that introducing a new vaccine would be quite different than launching a small molecule. Vaccines require a lot of foundation-laying work in the marketplace. For starters, here we have RSV disease, which is unfamiliar to most people, so we knew we needed to do disease-state awareness.” Trizzino applies his own “four Ps” concept to vaccine commercial readiness: product, policy, payer, and physician/patient.

“By product, I mean the target product profile that every marketing person talks about, but in this particular case, we collaboratively designed the target product profile with the R&D folks. I have a great relationship with Dr. Greg Glenn, the president of R&D, and from early on we were collaborating about what the product should look like, what the target populations should be, and what we are trying to accomplish for them. Are we simply preventing an infection, or are we preventing disease?”

He notes the answer in one case was the latter: The primary endpoint of the Phase 3 clinical trial in older adults is prevention of moderate to severe RSV disease, rather than total prevention of infection. “Why is that important? Because the older adult immune system, as a result of immunosenescence, is a hard immune system to stimulate. Therefore, we may not be able to prevent the infection entirely, but we want to prevent the more severe complications of that infection.”

Regulatory and public health policy also plays a special role in vaccines, says Trizzino, giving a key example. “You will not sell your vaccine unless you have supportive policy, most importantly coming from ACIP, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, but also from advocates for the vaccine in the healthcare practitioner community. A vaccine is not a treatment. It’s a prevention. So you communicate to people that they should want to be vaccinated to prevent something bad from happening.” ACIP evaluates and recommends vaccines, even issuing the pediatric and adult vaccination schedules. “An ACIP recommendation is critically important, so we had to begin early forming a working group to advise ACIP on RSV in advance of its formal review of our candidate.”

The third essential “P” is a payer strategy, says Trizzino. “Many times, no matter how many product marketing people get their hands on a great product, the last thing that they think about is a payer strategy. And when the product comes to market, the door is slammed shut. So we’re already considering what needs to be done there. We’re already in conversations with the CMS. We already understand the private pay implication, because it’s not a “65 and above” target product profile. It’s “60 and above,” which includes both Medicare and private pay. Anyone over 65 years will be covered by Medicare, but there’s still work to be done helping the CMS understand exactly what that coverage means.” For private insurance companies, Trizzino notes, the Affordable Care Act mandates that any ACIP-recommended vaccine must be covered at zero cost-share.

“We design a payer strategy that supports the target product profile that supports a policy recommendation, ensuring the product will be reimbursed. Marketing folks often refer to an access strategy — an access strategy is really nothing more than the coordination of policy and payer strategy. We want to set it up so people can easily find a healthcare provider that will vaccinate them, and their insurance will cover the vaccination. That means you go to the pharmacy or to the doc, pull out your insurance card and say, ‘I want to be vaccinated.’ You get vaccinated, and you walk out the door. That’s an access strategy.”

He is careful to clarify that the early conversations with payers do not include discussion of potential product price points. “We tell payers we will come to them with an economic model that makes sense. We start with a health-economics analysis, which we are already doing — cost-benefit models, quality-adjusted life years, pricing analogs, and other contextual data. All those things triangulate into a nice, reasonably tight range of pricing, which gives us the comfort of knowing we’ll be somewhere within this reasonable, palatable range compared to successful products already on the market.”

Trizzino says the last “P” is twofold — combining the physician and the patient. “This is about disease-state awareness,” he says. “We want the doc to be aware enough of the significance of RSV to make the recommendation, but we also want the target population to be aware enough of this disease that, if the doc isn’t recommending the vaccine, they’re asking the doc whether they can be vaccinated for RSV.”

He cites a “great example” of a successful awareness campaign that Pfizer conducted for the launch of Prevnar (diphtheria CRM197 protein) in older adults, called “Get this one done,” in combining disease-state awareness information delivered to healthcare providers with direct-to-consumer advertising. “Thanks to the Prevnar campaign, the importance of adult vaccinations is now more top of mind. More people are aware of the need for adult vaccinations.”

Does this sound like marketing now? Perhaps so, and conventional wisdom would say it has no place in precommercial development. But can a company afford to wait until regulatory approval before it begins to plan such a campaign? “Build it and they will come” may sometimes apply to an outright cure for terrible diseases or epidemics, but Trizzino’s point is merely logical: People do not seek out prevention so readily without adequate awareness of the disease and the preventative agent. The seeds of a marketing campaign must be sown early and mature through clinical insights as development proceeds to the end goal, and the product enters the commercial realm. By necessity and invention, Novavax is one company scouting down that path and, it hopes, all the way to the market.

AWARENESS TO ACCESS: THE VACCINE PATHWAY

John Trizzino, SVP of commercial operations at Novavax, shares some of the details of how the company is laying the groundwork for commercialization of its lead product, the RSV F vaccine for prevention of complications of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection, in one of its target patient populations: adults over 60 years of age:

John Trizzino, SVP of commercial operations at Novavax, shares some of the details of how the company is laying the groundwork for commercialization of its lead product, the RSV F vaccine for prevention of complications of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection, in one of its target patient populations: adults over 60 years of age:

TRIZZINO: We have to demonstrate the significance of the burden of disease in its frequency and its economic burden — why are we trying to vaccinate this population? Is it cost-effective? Here are some of the statistics: Our RSV vaccine’s target population of 60 years and older is now about 65 million people in the United States. By 2020, it will be 80 million. Every year, more than 5 percent of them will be infected with RSV. Of that 5 percent, about two-and-a-half million people today, by today’s statistics, 900,000 will have some kind of a medical intervention: an unscheduled visit to the doctor, an emergency room visit, or a hospitalization, all amounting to a direct cost burden to the system of some $3.5 billion. Also, more than 16,000 of them will die from RSV complications on an annual basis. The direct and indirect cost burden in the older adult population — from loss of life and exacerbation of underlying conditions, such as COPD, chronic heart or lung disease, and increase in frailty due to hospitalization — will likely exceed $30 billion in the United States alone. We factor all of those costs and implications to the healthcare system into the strategy. We also know we have the advantage of a relatively receptive target population of people who want to avoid conditions that could erode their quality of life as they age.