Sanofi Genzyme: Expanding Beyond Rare Disease Into Specialty Care

By Wayne Koberstein, Executive Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @WayneKoberstein

Moving from autonomous heritage to corporate integration as Sanofi’s new specialty-care business unit.

Two similarities between Genzyme and its parent company Sanofi strike home — both emerged as companies relatively recently, in the 1980s, and both ultimately took the industry by storm. My first visit to Sanofi, in 1989, happened at its tiny headquarters in a second-floor office flat on a nondescript street of Paris, where its then-CEO Jean-François Dehecq told me the little enterprise would someday conquer the world. As far as I know, Genzyme never made such a claim, but its accomplishments spoke for themselves.

Sanofi grew by aggressive acquisitions, by leaps and bounds, eventually absorbing many of the largest and some of the smallest pharma companies in France, Germany, the United States, and elsewhere. In contrast, Genzyme grew organically, becoming the third largest biotech company by the time Sanofi, then the third largest pharma, acquired it in 2011. Following the acquisition, Genzyme continued much as it was before, as an independent subsidiary focused mainly on rare diseases, most treatable with enzyme replacement, and beginning in 2011, multiple sclerosis. This year, however, Sanofi finally brought the Boston-based biopharma further into its corporate fold as a business unit, not to contain its portfolio, but to expand it.

MERGER OF MODELS

Some say Sanofi has removed many valuable and independent companies from the scene, but one could also say it has saved the essence of those companies from oblivion. It has certainly kept some valuable legacies alive, such as vaccines, insulin therapy, and cardiovascular drugs. It even inherited some of the heritage of Roussel Uclaf, developer of the medical abortion drug mifepristone, though the controversial product had been divested by the time Sanofi acquired Aventis (Hoechst Marion Roussel plus Rhône-Poulenc Rorer) in 2004.

Sanofi seems to have followed its natural bent for delving into the less-traveled realms of biopharma in acquiring Genzyme. With Sanofi Genzyme, however, the company has now taken the opportunity to adopt a new business model in tune with the industry’s general trend away from primary care and toward specialty care.

In the new corporate structure, Sanofi Genzyme has become the company’s specialty care business unit, with responsibility for four therapeutic areas: rare diseases, MS, immunology, and oncology. It is one of five business units in the company, joining Sanofi Pasteur (vaccines), Diabetes and Cardiovascular, General Medicines and Emerging Markets (including consumer health and generic medicines), and Merial (animal health). David Meeker, who was CEO of Genzyme, a Sanofi company before the change, has taken the new titles of executive VP and head of Sanofi Genzyme — not only reflecting a more European style of management-speak, but also reinforcing his direct reporting relationship to Sanofi’s CEO, Olivier Brandicourt.

From an outsider’s perspective, there is an evolutionary challenge implicit in the new structure of the company, reflecting changes in the industry as a whole: Which model will prevail, specialty care or primary care? Which one will grow the fastest? Which one will prove most profitable and valuable over time? Are the business units and the models they represent actually competing with each other in a corporate version of natural selection? The question bemuses Meeker, precisely because of its outside perspective.

“Inside the company, everyone wants to perform well, but there is no competition for survival between models,” he says. “All of the units are based on viable models, but their relative roles are changing, for many reasons. Medicine is becoming more targeted, and most of the innovation is coming in the development of new targeted medicines, which tend to be biologics disproportionately so their application is more complex and most often begins with a specialist.”

But it doesn’t always end there; in fact, as Meeker points out, specialists can often be the gatekeepers for much broader or longer-term use of a targeted drug under primary-care supervision. Premium pricing of specialty drugs is a driving issue in the scenario Meeker describes.

“Even if you have a common disease, but the therapy for it is highly innovative, you may need to go to a specialist in the early years to access the medication — often because the payers guide you there, counting on the specialist to ensure you have taken all the steps they require to justify its use and cost. Then, over time, the medicine may move to broad-based use perhaps in the primary care setting, though it has not been launched into a primary care setting.”

CUP RUNNING OVER

Growth in biopharma, it follows, may now depend largely on specialty care. The gatekeeper hypothesis explains one reason for the situation, but another reason is obviously the high revenue and profits that have returned to the industry in large part thanks to specialty care. Because of the relatively small patient populations, investment challenges, and risk-hedging in the area, specialty drug prices have lofted above those of traditional primary care products.

Several crucial distinctions exist, however, among the product types typically tagged with that term — from original drugs targeting disease mechanisms in new ways, to reformulated or repackaged older medications deemed essential for particular patient groups. For purposes of this article and its discussion of Sanofi Genzyme, specialty care drugs are innovative new agents of the type already described. And for the business unit, the specific opportunities for cutting-edge innovation lie chiefly in its therapeutic areas of focus.

Most of the unit’s prior experience has been in orphan drugs, with the major exception being MS. Yet even MS has a relatively small population of about two million globally. In our recent pricing roundtable (July 2016), Meeker credited Genzyme with inventing the orphan-drug business model in 1991, when it introduced Ceredase (alglucerase), an enzyme replacement therapy for Gaucher Disease later replaced by the recombinant version Cerezyme (imiglucerase). Gaucher then had a population of only about 2,000 patients in the United States. Genzyme made a good profit that helped build a much larger company, but it caught a great deal of flak for charging about $300,000 on average per year for the drug.

Payers ponied up, though, because the drug had miraculous results, the disease was truly rare, and the company supplied the drug free to qualified patients. At our roundtable, Meeker drew an important distinction, noting that most orphan-drug developers nowadays seek indications with populations close to the 200,000-patient maximum allowed under the Orphan Drug Act, but price the drugs at the high range formerly applied to drugs that treat much rarer diseases, such as Gaucher. Many, if not most new-drug developers, especially in cancer, now routinely try to claim orphan-drug status for their candidates.

In expanding into other specialty care areas, Sanofi Genzyme intends to apply valuable lessons learned from the rare disease space, but not insist every product conform to the high-population, high-payoff orphan drug model, according to Meeker. “We need to deal with both the lucrative and larger opportunities, but we will also have some that are much smaller and much more targeted, because that’s where science takes us,” he says.

“Prior to the restructuring, as a Sanofi company, we had the rare disease focus, which is at one end of the specialty care spectrum, based on the size of the target population. Now that we’re scaling up in multiple sclerosis, we cannot do everything the same as before, but the principles we follow as we approach the business do not change.”

Not only are patients with MS just as afflicted as those with a rare life-threatening disease, he says, but also the respective physicians treating both groups face similar challenges, such as bureaucratic pressure, time constraints, and more knowledgeable patients. The commonalities outline the unique conditions of each disease. “Specialty care is a big umbrella, and underneath the umbrella there are specific disease-by-disease differences for which we must customize our approach,” Meeker says.

He suggests Sanofi Genzyme will continue to plow undisturbed ground in the rare-disease space. “There are 7,000 rare diseases, and that number continues to grow, but only a few hundred have treatment, so there’s a huge unmet need there. For many rare diseases, the populations are so small, people will argue correctly that no commercial opportunity exists. But I believe the science, and I hope the regulatory framework, will continue to evolve in ways that increase the efficiency of developing therapies for rare diseases, so even when we could not completely rationalize the investment in a particular drug, we could go ahead and pursue development.”

INTO THE IMMUNE

One of the two new areas under Sanofi Genzyme’s responsibility is immunology, which currently focuses on immune-driven diseases, but will ultimately steer the business toward greater understanding of the immune system’s power to heal as well as destroy. The new responsibility also comes with a couple of advanced candidates: sarilumab, an anti-IL-6 antibody now in regulatory review at the FDA for rheumatoid arthritis; and dupilumab, an anti-IL-4/IL-13, also now in regulatory review at the FDA for its first indication in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Dupilumab, recently granted priority review by the FDA, is also in development for asthma and chronic sinusitis with nasal polyposis. Both of the agents entered Sanofi Genzyme’s pipeline through the collaboration between Sanofi and Regeneron.

The Phase 3 program for sarilumab included a comparison trial showing it achieved superior improvement from baseline over the leading RA treatment, Humira (adalimumab). Humira targets the tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a critical component in the disease pathway of RA and other autoimmune disorders, but Meeker suggests the IL-6 target may be even more important. “Some of the thought leaders have said, if anti-IL-6 had been introduced before anti-TNF, it might have been the mainstay of therapy instead of anti-TNF,” he says.

If approved, sarilumab would be the second antibody on the market to target the IL-6 receptor, after Actemra (tocilizumab), rather than the IL-6 molecule as does Sylvant (siltuximab). “When you’re second to market, you have the opportunity to build on prior knowledge, as well as what you learn incrementally in developing your own drug,” says Meeker. “One thing is especially clear at this point: The anti-IL-6 pathway is the central pathway in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis.”

Dupilumab essentially hits two targets through a single pathway involving TH2 (T helper 2 or CD4+ T) cells, which is implicated in seemingly disparate allergic conditions. Moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis is a serious, chronic form of eczema. Even though its symptoms appear on the skin, they are fueled by a continuous cycle of underlying inflammation triggered in part by a malfunction in the immune system. Asthma, of course, is a widespread and rapidly spreading disease. TH2s play a key role for a particular group of asthma patients with high levels of eosinophils, a type of allergy-related white blood cell, and possibly in a much larger subgroup with lower eosinophil counts but strong allergic activity.

“The asthma population that may be benefitted by manipulation of the TH2 pathway is larger than we originally thought,” Meeker says. “Patients with the allergic-type component may be responders to this approach.”

He says the actual programs had one main driver — “the biology.” Expanding knowledge from the ongoing research into autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms guided selection of the targets and creation of the candidate antibodies. “The science is so much better today,” he says. “We often look at this industry and wring our hands about all the challenges we face, but we may not always recognize just how fast the science is moving and the potential we have to solve real problems in medicine because of the better science.”

ONCOLOGY ONWARD

Understanding the immune system looks more and more like a convergent concept, covering more than autoimmunity and inflammation. Sanofi Genzyme enters immunology having some foundation in the field with MS. It may face a longer reach with oncology, even though Sanofi has remained active in the area ever since the initial days of Taxotere (docetaxel) and its acquisition with Aventis — via Rhône-Poulenc Rorer. But immunology could also serve as a kind of bridge to a new area of oncology, immunotherapy. Though Sanofi Genzyme may go down other avenues in the cancer area as well, most of my conversation with Meeker concerns its forays into immuno-oncology (IO). (See also, “Cancer Immunotherapy — Simpler Or More Complex?,” September 2016.)

“Immuno-oncology is a revolution,” he says. “It is still early, but the dramatic stories and data on some of the new immunotherapies are, I hope, just the tip of the iceberg. IO may give us the ability to harness the immune system to kill cancer down to the last cell and leave patients unharmed, unlike toxic chemotherapies, which kill only dividing cells. Now, how do we help tumors, which are not so visible to the immune system, become more visible? Which drugs should we use together to augment the response? IO will remain a major source of innovation and hope for cancer patients moving forward — though it raises some problems in the healthcare system when we start putting two or three expensive products together. That is a challenge we will have to meet.”

Brandicourt has declared the company does not aspire to be the number one company in oncology or IO, but to add value and differentiate itself in the field. Its collaboration with Regeneron includes an anti-PD-1 candidate in early development, and an anti-CD38 program that could be second to market, behind Darzalex (daratumumab) from J&J.

Meeker calls the early IO candidates “building blocks” in a program Sanofi Genzyme obviously intends to expand — a pursuit where the real competition in the field currently churns. No doubt, it will be one of the chief contenders for acquisition of top-performing immuno-stimulators and vaccines aimed at turning “cold” tumors, bearing low levels of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (TILs) into “hot” tumors with high TIL levels. (See Executive Editor’s Blog: “IO: Science Still Drives The Business.”)

THE MS MISSION

Sanofi Genzyme is well-embedded in the multiple sclerosis community. It markets two of the newest leading products for the disease — Aubagio (teriflunomide) and Lemtrada (alemtuzumab) — both approved in the past few years for relapsing forms of MS, and its pipeline holds an early stage candidate for the progressive form. (See “Developing New Therapeutics For Progressive MS,” June 2016.) The business puts extraordinary effort into patient associations, employee participation in MS fundraisers, and other support activities. Besides brand reinforcement, what does all the interaction with the patient community do for the company?

“The key issue for the MS community is understanding and predicting the natural history of the disease in individual patients,” says Meeker. “If physicians could be certain someone would develop progressive MS, they would want to use a high-efficacy therapy rather than a gentler therapy, before irreversible damage could occur. Also, as therapies improve, the expectations of the community can and should increase. Rather than slowing disease progression, patients will want to know, can you arrest it? We still don’t have a cure for MS and we still don’t fully understand the pathogenesis of MS.”

Meeker notes the “holy grail” for the MS community is remyelination, along with neuro-protection, which could offer reversal of disease and recovery of function. But neither Sanofi Genzyme nor any other company seems to be getting closer to that goal.

Meanwhile, he says, a “second-generation Lemtrada” is in development that will improve on its targeting of the immune cells likely to cause MS. “There are many drugs that modify the immune system’s response to MS disease. Lemtrada is somewhat unique; it also knocks back the immune system, but its benefit seems to be related to what happens after the repopulation of immune cells. The disease itself, in some cases, may be reset in a way that causes it to be much less severe. We continue to learn more about Lemtrada. Even though it’s already approved, we haven’t stopped researching it.” Apparently, this is a case of learn more about the therapy, learn more about the disease.

VAULTING VALUE

The same example illustrates a separate point: Innovation, in the sense of creating ever-better medicines, can and does come in countless forms, arriving from any of an infinite set of directions, but its ultimate arbiter is biology. Meeker reflects on what Sanofi Genzyme will do to preserve and enhance its ability not only to innovate, but also to obtain the fruits of innovation as another key arbiter, the market, changes around it.

“We are not a sales and marketing industry. The only way we can create sustainable value is to continue to innovate, and by definition, the value we create will always be rewarded,” he says. “We must continue to be a constructive voice at the table in shaping this healthcare ecosystem that we live in and depend on. It is both our personal responsibility and our company responsibility to be a part of the solution. For the company, innovation is not developing something new; innovation is built around understanding the problem we are trying to solve and then convincing others when we find a meaningful solution.”

In practice, the newly incarnated Sanofi Genzyme has a lot of new problems, or challenges, for which it must create solutions. For starters, the venerable campus in Cambridge, MA, will grow with new workers dedicated to the unit’s new therapeutic areas, immunology and oncology. Retention and recruitment will be a high priority, according to Meeker.

“The best way to attract good people is to have a true-value offering for the patients,” he says. “Will your product make a difference? Is it exciting and something people want to help develop? There are many places people can earn a paycheck. Most people in this industry still want to be earning it in a place that has meaning to them, where they get the satisfaction of making a difference in the lives of patients and physicians. We keep building a culture that keeps our highest meaning and purpose front and center. That makes us attractive and has always allowed us to hire good people.”

Of course, Sanofi Genzyme will continue to rely heavily on its external relationships, ranging from academia to joint ventures. And its ground-breaking work with patient associations will keep bearing fruit in future interactions, though generally, companies and patient groups will have to weather some emerging criticism of their “cozy” relationships from populist advocates. Some of the best research advances may well come from the less-heralded role of patient groups in bringing different companies together in pre-competitive interactions — a type of collaboration Meeker calls “coopetition.” (See “Heading the Sanofi Genzyme Business,” page 22.)

Many companies have melded into the fast-evolving world of Sanofi and faded into the corporate background. But, like Pasteur and a few others, the Genzyme name and spirit seem likely to survive in Sanofi Genzyme. As long as the specialty care model prevails or continues to play a leading role in biopharma, this business, its unique culture and capabilities, and its identity will likely remain a vital asset to its parent company.

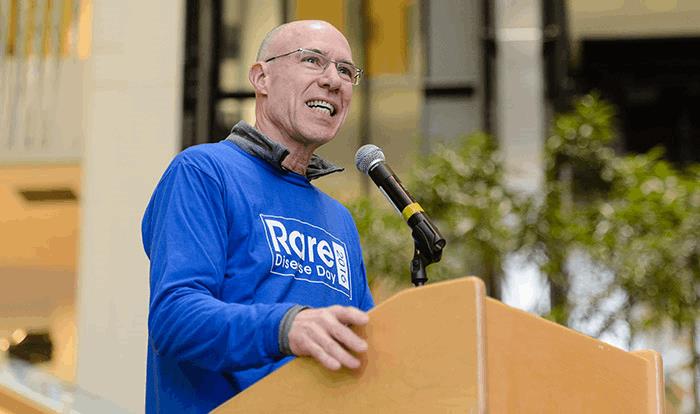

HEADING THE SANOFI GENZYME BUSINESS: DAVID MEEKER, M.D.

Telling his own story and a formative moment in his company’s history, David Meeker, M.D., heads the newly restructured specialty care business unit, formerly the company Genzyme and subsidiary of Sanofi:

Telling his own story and a formative moment in his company’s history, David Meeker, M.D., heads the newly restructured specialty care business unit, formerly the company Genzyme and subsidiary of Sanofi:

MEEKER: I’m a physician by training, and full-time critical care was my specialty. I practiced for a period of about seven years at the Cleveland Clinic, in the faculty position I held prior to coming to industry. I love medicine, and practicing medicine in that setting was one of the most rewarding periods of my life, but the intensive care part of the job was quite demanding, and when I got to age 40, I realized I probably wouldn’t be doing that until I was 60 and was open to other challenges. In 1994, a call came out of the blue from Genzyme, then a very early-stage company. The gene for cystic fibrosis was cloned in 1989, and Genzyme was one of a number of companies trying to find a gene therapy cure for CF. The belief was that it would be the first demonstration of the effectiveness of gene therapy. It was an incredibly exciting time, so I made the jump there, knowing what an incredible opportunity it was without really knowing exactly what my job would involve.

At that moment in history, a number of mostly small biotech-type startup companies and some of the best investigative researchers and molecular biologists in the world had been attracted to the field of CF gene therapy because that’s where the funding was. The convener was the patient community, and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation in the United States played a major role in bringing all of these groups together. It was a wonderful example, and regulatory authorities, including the FDA, were highly interactive. We lacked some of the formality then that governs our current interactions with the FDA, and there was a much steadier dialogue back and forth, almost patient by patient as we treated them, about every step we took. Across the entire community, many of us were competing, but in fact we were cooperating, so this was the best demonstration of “coopetition” I have ever seen.

Genzyme embarked on a number of gene therapy clinical trials for CF, but, although the studies showed evidence of pulmonary gene transfer, the efficiency was low. Over the past several years, the company has focused its efforts on developing small molecule solutions to address the underlying defect in patients with the Delta F508 mutation, the most common mutant allele in CF patients.