The Story Of Pfizer's R&D Turnaround

By Rob Wright, Chief Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @RfwrightLSL

“I was surprised at the magnitude of the challenge faced by Pfizer at the end of 2009, particularly in R&D,” recalls Mikael Dolsten, M.D., Ph.D., who is now the company’s chief scientific officer and president, worldwide research, development and medical (WRDM). He came to the company that year as part of the Wyeth acquisition. It was a difficult time for the Big Pharma as it faced the reality of $25 billion in revenue going off patent over the next few years.

The company was operating in 14 therapeutic and research areas and was well-known for having relied on traditional small molecules for sales (e.g., Zoloft, Lipitor, Norvasc, Zithromax). It also had a reputation for growing through M&A (i.e., 2000, takeover of Warner-Lambert; 2003, acquisition of Pharmacia; 2009, Wyeth acquisition). “We seemed more focused on acquiring companies than having confidence in developing new drugs via our internal R&D capabilities,” says Dolsten.

Pfizer wasn’t the only company at this time being accused of lacking innovation, but because of its size, it seemed to take the brunt of the criticism. That size, as Dolsten soon found out, had also created a hubris at the company that success would follow simply by doing things slightly better or by having stronger market-access capabilities. There was no need for any kind of radical reinvention of their existing R&D; the existing facilities would suffice. “We had a bit of a follower mentality,” he says. “We weren’t considering what a new innovation environment/facility looked like, and we didn’t have a lot of scientists who understood the new biomedicines.”

At this year’s BIO International Convention and Conference, Dolsten, Pfizer’s top scientist, sat down with me to discuss the decade spent rebuilding the company’s R&D competencies toward leading — not following.

CREATING A NEW R&D STRUCTURE

Developing a “turnaround” plan at any size company is a daunting task, but recognizing that this kind of change is a priority while at the same time trying to integrate two industry behemoths is … well, overwhelming. This was the case for Dolsten, too, even though he had been through a few M&As already and had gained plenty of experience successfully merging two companies.

To understand the sheer scope of this challenge, remember that at the time of the acquisition, Wyeth employed around 48,000, sold products in 145 countries, and had numerous international manufacturing and research facilities. “I started this journey with Pfizer CEO Jeff Kindler, who, with Bernard Poussot, the CEO of Wyeth at the time of acquisition, shaped the integration,” he shares. And while Dolsten credits Kindler with contributing to his perspective that Pfizer needed to go beyond just small molecule pills, he credits Kindler’s successor for really making the difference. “Working with Ian Read, we were able to develop a forward-looking 10-point turnaround plan to fix Pfizer’s R&D innovation core.”

During the Wyeth integration, Dolsten and his team focused on developing a new R&D structure with a trimmed pipeline. “Being in 14 therapeutic areas made it impossible for Pfizer to lead,” he explains. “We needed to prioritize in which areas we wanted to be.” To do this, the team looked at areas of science where Pfizer was among the top three leaders and then evaluated each area to determine if it was somewhere innovation might flourish. This exercise resulted in those 14 therapeutic areas being winnowed down to five.

Pfizer first anchored around oncology, as the team believed their skills in designing molecules could help advance this area. The second therapeutic area was inflammation and immunology, as Dolsten notes each has the underpinning for so many diseases. “Building Xeljanz, one of the first and most successful JAK protein inhibitors with three indications, is one of the reasons why we now have 11 different next-generation JAK programs currently in the clinic,” he shares as an example. The third therapeutic category was built on Wyeth’s strength in pneumococcal vaccines. “But we really needed to move away from essentially being a single vaccine company to having a pipeline that included bacterial, viral, and cancer vaccines, which we now have.” Pfizer determined it also wanted to continue in the internal medicine space, which it viewed as important for patients in the Western and developing worlds. “We thought the spiraling epidemics in obesity and diabetes would drive a tremendous need for new medicines,” he explains. “We built on the core of what we had, but then recruited top biomedical thinkers and innovators to join us.” The last focus area involved the company’s legacy hemophilia and growth hormones business. “Originally, we were thinking of making a gradual exit, as we didn’t see apparent innovation, but as we did our analysis, we started to think about these as being rare diseases and areas that provided insight into the genetics of why certain patients are born with a mutation that leads to disease.” He believes this decision was one of the company’s most brilliant moves because it came about a decade after the first sequencing of the human genome, and it took almost 10 years to turn the language of DNA into understanding of its function. As the company began to build its rare-disease pipeline, the team became intrigued with not just creating the original type of medicines (e.g., small molecule protein replacements that modulate some genes) but actually being able to restore faulty genes. “That led to Pfizer to being one of the first Big Pharmas to invest in gene therapy, and that gave rare diseases a completely new shape,” Dolsten states.

A NEW MODEL FOR NEUROSCIENCE

Though the period of redefining Pfizer’s therapeutic R&D areas was an exciting time, it also was emotionally challenging. After all, because it was determined that Pfizer wouldn’t be among the top three leaders of a therapeutic category, it was leaving some areas where it had significant history. The most noteworthy exit was neuroscience. “This was very difficult given there is tremendous unmet medical need in neuroscience,” Dolsten admits.

Instead of totally abandoning the space, the plan was to find a new model — a new way for the company to par-ticipate and drive innovation. With the help of Bain Capital, Pfizer spun out its neuroscience pipeline into a newly created company, Cerevel Therapeutics. At the same time, Pfizer put in place a five-year plan to invest $600 million as a VC fund, with up to $150 million going into neuroscience. In other words, the company was (and still is) seeding neuroscience advancements while contributing innovation to new CNS endeavors via Cerevel. Dolsten notes this model already had been used to seed oncology, inflammation, and rare-disease companies.

DOING JUST A FEW THINGS AND DOING THOSE REALLY WELL

“Let me share another example of how Pfizer is thinking differently about R&D,” he states. “For those five therapeutic areas in which we are now focused, we are striving to select no more than three major aspects where we think we can be a leader.” For example, in oncology, Pfizer focuses a lot on cell-cycle regulation, which was part of the success behind Ibrance in breast cancer. But the company also was active in CAR-T cell therapy, a form of immunotherapy using specially altered T cells to fight cancer. As leadership was evaluating oncology R&D, they realized the need to apply the same disciplined approach to investment in Pfizer oncology as it had with neuroscience. “We concluded that for Pfizer to win, it would be better to focus on doing just a few things and doing those really well.” As such, the company entered into a CAR-T asset contribution agreement with Allogene Therapeutics. In doing so, Pfizer is now the largest minority owner in Allogene and is helping to seed industry innovation.

This more focused approach to R&D also came with a plan to trim $3 billion from the combined Wyeth/Pfizer R&D budget of $10 billion. “Sometimes having less forces you to make hard decisions and prioritize,” Dolsten elaborates. Hence, the company’s plan to build and invest in areas viewed as good opportunities, thereby creating a modality-based approach for Pfizer scientists.

In addition, Pfizer wanted to improve upon its leadership decision making. “A lot of work was done to counter the mindset of just doing more of the same because that’s where you started.” Dolsten says the company even brought in behavioral psychologists to help employees better understand how to recognize their own bias. “In revamping the R&D pipeline, we needed not only better science, but better and more-quantitative decision making, and better overall effectiveness across the entire Pfizer R&D group.”

AN UNUSUAL PRESENTATION APPROACH

Over the past decade, Pfizer built a completely new pipeline with 97 programs (it had 133 programs in development in 2010) that include biologics, biosimilars, and those with Breakthrough, Fast-Track, orphan, and PRIME designations. More than half are new molecular entities (NME). Furthermore, Dolsten says that by engaging more with the biotech community, as the company was actively doing at the 2019 BIO International Convention, Pfizer continues to advance its capabilities (e.g., gene therapy) while maintaining leadership in small molecule pills and vaccines.

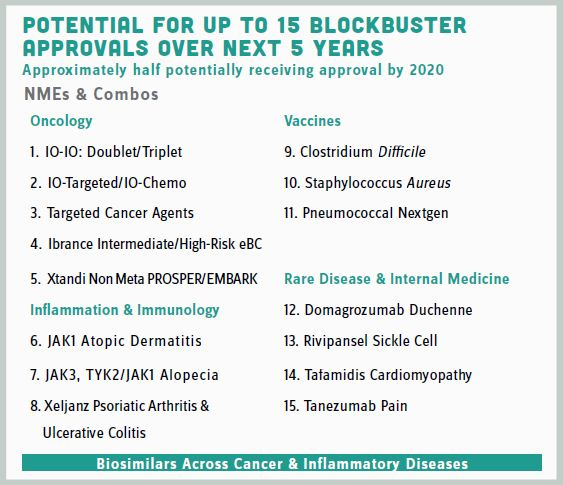

To help share the story of Pfizer’s R&D turnaround, Dolsten was asked to represent the company at the 2017 Goldman Sachs Healthcare Conference (June) in LA. In preparing his presentation, he decided he wanted to do something different and powerful. “We discussed having just two slides, one showing the overall priorities, and a second one listing the top 15 pipeline products that could deliver blockbuster potential over the next five years [i.e., 15 in 5].”

The idea received mixed reviews at an executive team meeting (i.e., “What if too many of the 15 fail? Should we be so transparent as there seems more risk than upside?”). Though such a radical approach had never been tried before, Ian Read gave Dolsten the green light. “Following the presentation, we started to see comments touting ours as the most focused investor presentation they had ever seen,” he laughs. Indeed, he believes that after this presentation, the investor community began viewing Pfizer as a growth company worthy of investing in. Gone was the impression of the company as being solely great at marketing and M&A, but not so strong at R&D. “The highly focused 15 in 5 enabled us to also better update investors, as we could go through and tick boxes on progress and setbacks for each therapeutic area,” Dolsten says.

Pfizer is at about the halfway point on its 15 in 5 plan, and according to Dolsten, there have been more successes than failures. Still, the company remains cautiously optimistic, with Dolsten frequently reminding people that not all 15 products will be blockbusters, and some will likely fail. But even with some expected pipeline attrition, Pfizer still anticipates 25 to 30 approvals by 2022!

To be a leader in the biopharma innovation ecosystem requires a multifaceted approach. For Pfizer, that meant acquiring companies, being an early partner, working as a seed investor, spinning out assets, improving its R&D leadership decision making, and having thought-leading and focused R&D. But the true proof of a turnaround resides in drugs being approved. Since 2011, Pfizer (as of this writing) has had 40 approvals — half being NMEs.

“We wanted to foster a climate where we moved from being followers to pioneering leaders in areas where we could sustain a leadership position,” Dolsten explains. “I’m proud of where Pfizer is today. We are an iconic American pharma with vibrant science, a strong pipeline, and a solid capital structure. And, we’re growing such that we can afford to increase our investment in R&D.”

THE DEALS THAT DIDN’T HAPPEN

Although Pfizer is no longer relying on M&As to be the primary driver of its R&D engine, the Big Pharma is still engaged in doing deals. For example, it has partnered with Spark Therapeutics and Sangamo Therapeutics, it bought a 15 percent stake in Vivet Therapeutics, it also acquired Bamboo Therapeutics in a deal worth up to $645 million, and more recently, acquired Array BioPharma in a transaction valued at approximately $11.4 billion. But do you recall the biggest deals not to happen during Pfizer’s period of R&D turnaround?

In 2014, Pfizer abandoned a $118 billion attempt to acquire AstraZeneca (headquartered in the U.K.). Two years later, Pfizer and Allergan (headquartered in Ireland) had their planned corporate inversion blocked by the U.S. Treasury. However, both attempts turned out not to be necessary. “These M&As were difficult because of the political environment at the time,” reminds Mikael Dolsten, M.D., Ph.D., Pfizer’s chief scientific officer and president, worldwide research, development and medical (WRDM). Back then, American companies faced a less-favorable tax structure when compared to those located outside the U.S. “But as that has been corrected, perhaps those M&A activities helped shed light on what needed to happen in corporate America,” he smiles. “Meanwhile, our R&D turnaround gave us an alternative and less-turbulent path to innovation and growth than large M&As.” And while you can never say never to a potential big merger that maximizes shareholder value, right now Pfizer is focused on its own pipeline, and adding products to it, either through internal development or acquisition of smaller companies.