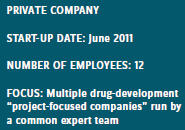

Velocity Pharmaceutical Development: A Novel Start-Up Model

By Wayne Koberstein, Executive Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @WayneKoberstein

The Enterprisers: Life Science Leadership In Action

Velocity starts with the drug and supplies everything else needed to support drug development — capital, management, and development expertise. It puts each of its licensed drugs inside an utterly virtual company with all the essential legal and financial wherewithal and none of the usual “encumbrances” such as permanent employees and infrastructure mirroring the standard corporate structure.

Velocity starts with the drug and supplies everything else needed to support drug development — capital, management, and development expertise. It puts each of its licensed drugs inside an utterly virtual company with all the essential legal and financial wherewithal and none of the usual “encumbrances” such as permanent employees and infrastructure mirroring the standard corporate structure.

As the umbrella over a growing portfolio of such single-product, “project-focused” companies, Velocity houses a common team of managers and experts who oversee all of the entities and push each one’s drug asset through proof-of-concept in humans. The company has even come up with its own descriptor for the virtual drug-development model it is pioneering: “asset-centric virtual development.” With capital from the founding CEO’s VC firm, Presidio Partners (formerly known as CMEA Capital) and Remeditex Ventures, Velocity has so far launched four project-focused companies, all named for aeronautic notables: Tigercat, Spitfire, Corsair, and Mustang. The first of them, Tigercat, may have a tiger by the tail with its potential blockbuster candidate, serlopitant, for chronic pruritus (severe itching), licensed from Merck along with plenty of good safety data to propel it.

“After the stock markets went crazy in 2000, there were very few IPOs for the next 13 years,” says Dr. James Larrick, Velocity’s managing director and one of its three chief medical officers. “So as an alternative to IPOs, as well as to the traditional start-up or the so-called virtual organization with its own exclusive management team, we came up with this project-focused company model at CMEA. In Tigercat’s case, we sought to develop VPD-737 in a virtual manner and sell it after we have Phase 2 data.”

SINGLE TEAM, PLURAL PACKAGES

Founders, managers, and employees of the typical life sciences company must bet their lives, careers, and fortunes on the success of drug development. Sometimes, as industry observers know well, the stakes are too high to admit defeat. Even when trials fail and the candidate is doomed, companies continue operating on their own momentum, and burning capital, beyond their usefulness. Dr. David Collier, CEO, says the Velocity model removes the motivation for ensconced management postponing the inevitable.

“Everybody at Velocity is working on all of the programs, and so everybody has an incentive to keep working on the ones that will succeed and to kill the ones that will not,” Collier says. “In a traditional biotech, where there is a management team and a board of VCs who have all invested, there are perverse incentives to keep on going, to run another trial in the subset of patients where a drug may have worked, because people don’t want to lose their jobs and VCs don’t want to take the write-offs. It is always easier to put more money in than to just kill the whole thing. Our thesis is that we can get a lot more done with a lot less money because we only have one team spread over all the projects.”

Forming a separate company around every asset also changes the way the assets are obtained, how licensors are compensated, and how the companies are financed, according to Collier. “When we acquire a drug for a virtual company we have created from scratch, we try to buy the drug by trading stock in the company. We are venture-funded and cash is expensive, so we don’t want to pay $20 million up front and agree to a bunch of milestones. What we bring to the equation is a very experienced clinical development team and the funding to take the drug through clinical proof-of-concept. We divide up the ownership of the company proportionally depending on the value of the funding, the team, and the drug. If the drug is successful, the upside for its originator is owning a significant equity stake in our company. After showing the drug works, we can then sell the asset back to the originator or to another company.”

Another CMO, Andrew Perlman, M.D., Ph.D., is a drug-development expert who hails from Genentech and Tularik and was also the founder/CEO of Innate Immune. But Collier gives credit for inspiring the Velocity model to CMO Edward Schnipper, M.D., who brought the seeds of the concept to Presidio in 2003. At the time, Schnipper was the CEO of Cellgate (since purchased by Progen) and confessed to having free time on his hands while waiting for results from two clinical trials conducted by a CRO.

Collier describes his approach. “Ed said, ‘The way VCs fund these companies is nuts! You build this management team, you hire all these expensive people, and they are really busy for only a short time and then must wait for the trial to read out, and you’re spending all of this money. Let’s figure out a way you can spread me across a lot more clinical development and use my time more efficiently.’ After he helped us on several other projects, we struck on the idea of having a central team to manage multiple asset-centric companies.”

Although many other VCs are now experimenting with capital-light companies in virtual development of novel drugs, Collier believes Velocity has the “most virtual” model. He mentions Atlas and Index Ventures as firms that employ a core consulting team to advise or sometimes run the companies they fund. But, he argues, the economic incentives for those people are still largely tied to the fate of particular products. In another example, Lilly and TVM Capital have partnered to select certain drugs out of Lilly’s pipeline, use the fund’s money to develop the drugs into proof-of-concept, and then give Lilly an opportunity to buy them back again. Similarly, Swiss-company Debiopharm combines expertise along with a pool of money, licensing in drugs from the outside and developing them within the company rather than creating separate legal entities for each drug as does Velocity.

“Putting each drug inside a separate company makes it a really simple package for a pharma company to acquire,” he says. “Pharma companies are accustomed to buying biotech companies, but the part they don’t like is the people and all of the liabilities that go with them. So we give them a company that has never had any employees or even an office. There is nothing in the deal other than the IP for the drug, the clinical data, and the contract with the CRO and the contract with Velocity. Due diligence is clean and simple. It also works for financial reasons because Velocity is funded by only venture capital.”

Collier explains that, if a pharma company were simply to license the drug, it would wind up in a double-taxation situation, but in the Velocity model, it would just buy the virtual company outright, which is not a taxable event by itself. The money exchanged would flow back as a capital gain to the investors in the fund, leaving only one level of taxation instead of two.

Collier emphasizes the unique aspects of the Velocity model. “Unlike a lot of the other variations on our model, the team we’ve built here is a clinical development team, and the expertise around the table is in developing drugs. Many of the other programs are run by VCs who have investing experience, but no real drug-development experience. But I am the only VC in the crowd here; everyone else has a long history of successfully developing drugs.”

It will likely be many years before the success or failure of Velocity plays out and we know whether its model actually worked as planned. Meanwhile, many people will be watching how well the company implements its “asset-centric virtual development” concept, which will continue to challenge the conventional notion of life sciences start-ups, and we shall see what is really essential and nonessential in a virtual company.

Do you have something to say about Velocity and its start-up drug-development model? Please post your comments online with this article under Current Issue (June 2015) or Past Issues at lifescienceleader.com.

The Tigercat Stalks Pruritus

In December 2014, Velocity’s “project-focused” company, Tigercat Pharma, announced positive results from a Phase 2 study of its oral NK-1 receptor antagonist VPD-737 (serlopitant), for patients with severe, chronic itching (pruritus) who failed to respond well to the current standard-of-care treatments, topical steroids, and antihistamines. Two of Velocity’s cofounders, Chief Medical Officer James Larrick and CEO David Collier, tell how the drug’s Phase 2 results have exceeded expectations, possibly giving the company a big hit the first time out.

“Chronic pruritus will become a major indication for the pharma industry,” says Larrick. “It is like other conditions that previously were considered to be an inevitable part of life until the pharma industry developed drug therapies for them — restless leg syndrome, erectile dysfunction, overactive bladder — and chronic pruritus may be one of those. We believe serlopitant is the beginning of a blockbuster category of drugs. It would be both first-in-class and best-in-class.”

Collier elaborates on the potential market for the pruritus, a condition considerably more severe than most people likely realize. “Pruritus is a lot like chronic pain. It is frustrating for physicians because there are patients who are in incredible need. It destroys their lives — they can’t work, they can’t sleep, and in extreme cases, they’re suicidal because there is nothing to help them. Pruritus is recognized as one of the big unmet needs in dermatology, and surveys suggest a multimillion patient market exists in the United States. Perhaps 20 to 30 percent of the population over age 65 has problematic itching.”

Tigercat’s Phase 2 trial of serlopitant was a 257-patient, four-arm, 25-center, prospective, placebo-controlled randomized trial that demonstrated high safety and efficacy, according to Collier and Larrick. Merck, from which Tigercat licensed the drug, had already tested the drug in over 900 patients in various other indications, generating a wealth of positive safety data.

“The Tigercat asset is a great example of our model’s speed and capital efficiency,” says Collier. “We moved it from licensing to the end of the Phase 2 trial in under two years and at a total cost of only $12 million, almost all of which was spent running the trial.”

Speed and capital efficiency have become ever more valuable assets in themselves, as many life science entrepreneurs will attest. Velocity’s “asset-centric” model may be paying off already in Tigercat.

Companies With Wings

Velocity has officially launched four virtual companies, all with their aeronautic names, but it has released detailed public information on only two of them, Tigercat and Spitfire. All of the companies besides Tigercat are still at the preclinical stage. Among the other three, Spitfi re is furthest along, with a novel dual GLP-1/glucagon receptor agonist for treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity. Tests on animal models of those two conditions have shown significant weight loss and glucose reduction following treatment with advanced drug candidates.

The most advanced lead is a novel peptide compound with the extended-release technology, EuPort, licensed from its developer EuMederis. With the drug, Velocity hopes to match better-than-standard glycemic control with significant weight reduction through a weekly subcutaneous injection.

“Our current thinking is we need to take this peptide into a human proof-of-concept trial before we sell it, and we’re still trying to figure out exactly what that study needs to look like,” says CEO David Collier. “So we’re talking to pharma companies to get their input on what data they would want to see.”

Velocity has not yet revealed details of its plans for the remaining two companies, Corsair and Mustang. It says Corsair is developing a pulmonary disease drug, but will not be releasing more information until at least the end of 2015. Mustang remains shrouded in confidentiality.