Obamacare Is Vaporizing Retiree Drug Coverage

By John McManus, The McManus Group, jmcmanus@mcmanusgrp.com

The headlines have been filled with reports of thousands of individuals losing their health insurance because many plans in the individual market do not conform to certain requirements of Obamacare. But what is not well-known is that employer-sponsored retiree drug coverage for Medicare-eligible beneficiaries has virtually evaporated as a result of enactment of Obamacare.

The headlines have been filled with reports of thousands of individuals losing their health insurance because many plans in the individual market do not conform to certain requirements of Obamacare. But what is not well-known is that employer-sponsored retiree drug coverage for Medicare-eligible beneficiaries has virtually evaporated as a result of enactment of Obamacare.

Some background: The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, which integrated prescription drugs into Medicare, provided for a tax-free “retiree drug subsidy” to employers that offer qualified drug coverage to Medicare-eligible retirees. That subsidy is equal to about two-thirds of the value of the subsidy for Part D drug plans. This retiree drug subsidy was meant to leverage — but not replace — the private coverage in the market. By doing so, it would help individuals retain their current coverage and limit the expenditure of taxpayer dollars. To the degree retirees retain drug coverage from their employers, Medicare saves money.

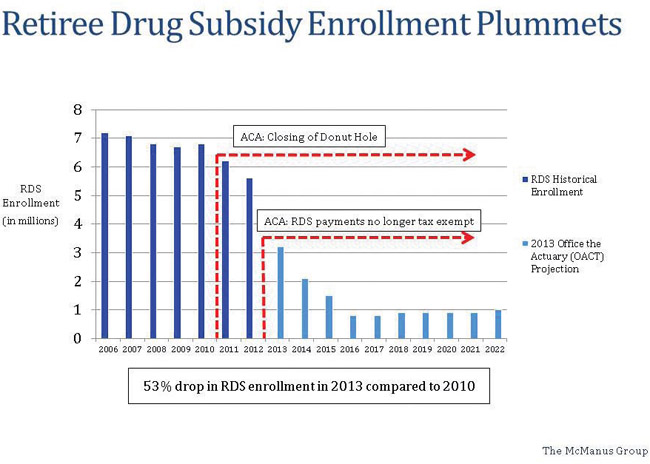

Analysis from the CMS Office of the Actuary (OACT) shows that the subsidy achieved that goal for the first five years of the program. From 2006 to 2010 the number of individuals receiving the retiree drug subsidy remained stable at about 7 million.

But in 2011, the number dropped to about 6 million. In 2012, it declined to 5.7 million. Then in 2013 the bottom dropped out of the market, with the number of individuals receiving the retiree drug subsidy plunging to about 3 million. OACT projects this number to fall to less than 1 million by 2016 and beyond. (See chart on page 12.)

What Happened?

Obamacare made two substantial changes to the Medicare drug benefit. Most importantly, it filled the “donut hole” — the $3,610 gap in coverage in 2010 between the initial benefit and the catastrophic protection. That feature of the benefit was a result of the limited resources available when Congress enacted drug coverage in 2003, and Democrats vowed to address the issue when they took power.

Starting in 2011, brand-name pharmaceutical manufacturers were required to provide 50% discounts for drugs purchased in the donut hole. This made a substantial difference for many beneficiaries as the Congressional Budget Office observed that about one-fifth of spending by non-low-income beneficiaries was for drugs in the donut hole.

Simultaneously, the statute closes the donut hole by gradually increasing the initial benefit threshold and dropping the catastrophic attachment point over 10 years. By 2020, the donut hole is eliminated and beneficiaries will receive 75% coverage, on average, of their drugs before the catastrophic protection kicks in.

Secondly, Obamacare repeals the tax-free nature of the retiree drug subsidy. (This was, interestingly, the provision that sealed the bipartisan deal between then Ways and Means Chairman Bill Thomas [R-CA] and Finance Ranking Member Max Baucus [D-MT] 10 years ago.) By making the retiree subsidy taxable income, this had the effect of decreasing the value of the subsidy by the corporation’s marginal tax rate — up to 35 percent in many cases.

PhRMA agreed to the 50 percent discount, in part, to deter a worse alternative — Medicaid rebates on the Part D drug benefit. But the industry also benefited from the provision because it had noticed that many beneficiaries often discontinued their prescriptions when they hit the donut hole. The 50 percent discount helped beneficiaries stay on their meds and get to the catastrophic protection, where 95 percent of costs are covered.

Employers also took note that this more generous coverage is available in Part D prescription drug and Medicare Advantage plans, but not under their own retiree plans. Employers, of course, are in the business of producing widgets, not providing health coverage. And it is economically irrational to leave money on the table. IBM, for example, discontinued retiree drug coverage and directed their retirees to coverage available under Medicare drug plans and Medicare Advantage.

What Lessons Can Be Learned?

The press has been understandably focused on the disastrous rollout of Healthcare.gov and the relatively few individuals who have signed up for coverage.

But a more troubling concern over the long term will be whether employers react similarly for their current workers as they have for their retirees’ drug coverage.

My first column for Life Science Leader, published last spring, detailed the compelling math for an employer of lower- or middle-income workers to dump their employees into Obamacare. The modest $2,000 penalty for large employers failing to provide coverage pales in comparison to the substantial subsidies available in Obamacare to lower- and middle-income workers. For example, an employer offering typical coverage to a family of four with an income of $48,000 would save $7,400, even after it covers the increased income and payroll taxes that result from moving nontaxable benefits into taxable wages.

So the real risk is not whether too few sign up for Obamacare, but too many. The Congressional Budget Office predicts that only 8 million individuals will lose their employer-sponsored coverage. But if just 10 percent of employees with employer-sponsored coverage are dumped into the exchange, that number will double to 16 million.

Employer dumping of coverage will result in painful coverage disruptions with more narrow provider networks and tighter drug formularies in Obamacare. Just as importantly, it will require greater government subsidies that will, in turn, result in greater scrutiny over pricing and increased pressure to restrain costs.