Washington's Baseless Sense Of Complacency On Entitlement Reform

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

For more than a year, Washington was gripped with the prospects of a grand bargain whereby the country would finally put its fiscal house in order and the two parties would come together on a package of shared sacrifice of entitlement cuts and revenue increases.

For more than a year, Washington was gripped with the prospects of a grand bargain whereby the country would finally put its fiscal house in order and the two parties would come together on a package of shared sacrifice of entitlement cuts and revenue increases.

But no longer. President Obama lackadaisically issued his budget blueprint two months late. And other than reducing projected inflation updates for Social Security and marginal tax rates, it contained no bold ideas. No fundamental Medicare reform was put on the table, despite bipartisan interest, and no real savings proposed at all from either the burgeoning Medicaid program for the poor or Obamacare itself, which the President’s own actuaries had already predicted to be massively more expensive than initially forecast.

Then in May, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) observed that the annual deficit will shrink to $642 billion this year, down from the $1 trillion plus annual deficits that the Obama Administration has racked up every year in office. A combination of higher revenue from the fiscal cliff deal, profits from Freddie and Fannie, the budget sequester, which is effectively cutting discretionary spending, and slowing health costs have led to the improved budget outlook.

As a result of these developments, the date when Congress will have to enact an increase to the debt ceiling has been pushed back from May to November, and a feeling of sanguinity has enveloped the capital that all is well with the nation’s finances and no further action is necessary at this time.

Nonetheless, the fundamental fiscal challenges that confront the country in the long-term have not changed:

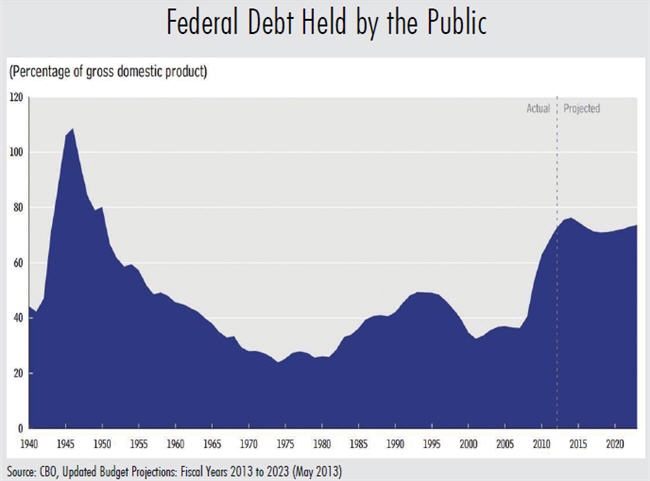

Federal debt held by the public is projected to remain historically high relative to the size of the economy for the next decade at 77% of GDP — a level not hit since the 1940s when the nation had to finance the massive undertaking of World War II.

Both revenues and outlays over the next 10 years are projected to be substantially above their 40-year averages: Revenues will grow from 15.8% of GDP in 2012 to 19.1% of GDP in 2015 compared to a historical average of 17.9%. Although outlays have fallen from their 2009 high of 25.2% of GDP, they will still remain well above the historic average of 21%.

Medicare costs under the U.S. Trustee’s current law assumptions will rise from their current level of 3.6% of GDP to 5.8% in 2040 and 6.5% in 2087. Under a more realistic forecast, in which the slated 25% physician-payment cuts are not allowed to go into effect, Medicare costs will rise to 6.1% of GDP in 2040 and 7.2% in 2087.

With 11,000 Baby Boomers aging into Medicare every day, the country still has not fundamentally prepared for the demographic shift of a ballooning aging population living longer and using more Social Security and Medicare resources with fewer workers to support them.

More troubling is that the Medicare Trustees report, which is supposed to inform policy makers on the health of the Medicare program, is entirely detached from the fundamental fiscal strains the country confronts to finance the program. For example, this year’s report produced headlines in newspapers across the country of an improving fiscal picture — Medicare’s trust fund will go broke in 2026, two years later than last year’s projection.

Yet that factoid totally obscures the reality that Medicare is massively underfunded because the Medicare trust fund only records dedicated payroll tax revenue and premiums for Medicare inpatient spending. All outpatient spending — physician services, prescription drugs, hospital outpatient departments, etc. — is financed just 25% through beneficiary premiums and 75% from general revenue. Since healthcare is increasingly migrating to the outpatient setting, the solvency of the inpatient Part A Trust Fund really is not relevant to the financial obligations taxpayers have for financing seniors’ healthcare.

A snapshot of 2012 demonstrates the extent of the budgetary sleight of hand in mixing dedicated funding sources with General Fund revenue. In FY 2012, Social Security and Medicare benefits cost $1.32 trillion. Payroll taxes, Medicare premiums, and other fees for these programs equal $920 billion, creating a deficit of $403 billion — $243 billion for Medicare and $160 billion for Social Security. This shortfall has to be covered by general revenue and is a driving force behind the budget deficit.

The Trustee’s long-term outlook is even more foreboding with a 50% shortfall for Social Security and Medicare over the next 75 years, where dedicated taxes and premiums will only cover $73.2 trillion of the expected $112.8 trillion of spending.

Things aren’t getting better. They are getting worse more slowly.

And what is the administration’s answer to this? On “Good Morning America” on March 13, President Obama said, “We don’t have an immediate crisis in terms of debt. In fact, for the next 10 years, it’s gonna be in a sustainable place.”

What is sustainable about the two-pillar entitlement programs for the elderly being underfunded by 50%, to say nothing of his entirely new health program or Medicaid?

What Should Be Done?

First, we as a country must recognize that although there has been marginal improvement in the fiscal situation, the fundamental problems remain. Second, we must acknowledge today’s seniors and future seniors are entitled to and will receive far more in benefits than they ever paid into the system. Third, seniors need to have more skin in the game and become actively engaged in making decisions that will save resources for both the system and themselves.

For Medicare, this means we must move to a more competitive system and away from the command and control of price-by-government fiat. This has been done already to great success in Medicare Part D, where seniors get to choose the prescription drug plan that best fits their needs and share in the savings when they make economical choices through lower premiums. But the entire system should move in this direction. If seniors want to remain in the present government-run system, then they should pay the difference between that system and competing health plans that can offer the same benefits for less.

In addition, the current Medicare fee-for-service program’s cost-sharing requirements should be modernized to better align beneficiary choices with costs. For example, healthcare reform made preventive benefits entirely free to beneficiaries, thereby masking massive price differentials for the identical service provided in different sites of care. A Medicare beneficiary does not know that a diagnostic colonoscopy is twice as expensive in a hospital as it is in an ambulatory surgery center.

Similarly, millions of Medicare beneficiaries have Medigap plans which provide supplemental first-dollar coverage, making almost all benefits appear free to the beneficiary. CBO has estimated that simply prohibiting first-dollar coverage of Medigap would save over $50 billion.

But all of these ideas are moot if the President and Congress fall into a false sense of complacency that the fiscal situation is fundamentally sound and no action is necessary.

Skeptics will say that divided government produces paralysis. I say that divided government actually is essential for changes of this magnitude because it requires both parties to offer their ideas and take ownership of the solutions.