A Future-Back Approach To Transformative Therapies

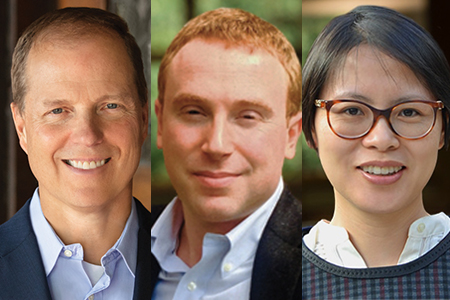

By Mark Johnson, Josh Suskewicz, and Xiaoxing Wang

This isn’t news. Capital raises for companies in this space increased from $4.2 billion to $13.3 billion between 2016 and 2018, more than 1,000 clinical trials are underway around the world, and the first wave of new drugs has launched in recent years, most targeting rare monogenic diseases, such as Zolgensma for spinal muscular atrophy and Luxturna for certain inherited retinal diseases. Just about every major biopharma has begun to place their bets, highlighted by Gilead’s $11.9 billion acquisition of Kite and its CAR-T platform in 2018 and Novartis’ $8.7 billion acquisition of AveXis to secure Zolgensma and its gene therapy platform.

But to truly capture the potential of transformative innovations, many of which will take years to pay off, biopharma leaders need to trade their default “present- forward” mindset for one that is “future-back.”

TECHNOLOGIES DON’T REPLACE TECHNOLOGIES, SYSTEMS REPLACE SYSTEMS

What do we mean by “present-forward” and “future- back?” Present-forward is when you take an existing strategy or product and improve it by increments — you start with the present, and project it forward. Future-back is when you set aside today’s realities, assert a bold new vision for the future, and build toward it systematically — from the future back to today.

To bring this to life, consider the recent transformation of a very different industry. As with biopharma today, cell phones stood on the cusp of a transformational inflection in the early to mid-2000s. Everyone could see that smartphones were coming, and everyone placed their bets. Most companies added computational capability to their existing phones, making them smarter. This led to the creation of better cell phones, certainly — but also a vulnerability to disruption. The iPhone debuted in 2007 as a pocket computer that happened to have cellular capability, changing the category and upending the entire industry.

How did Apple do it? Steve Jobs’ fabled leadership quirks are very well-known; what is less well-known but central to the tale is the way that Jobs tied his vision to a deliberate strategy, which was to develop a unified virtual and mobile ecosystem, anchored by key products.

Back in 1999, Jobs and his lieutenants foresaw the commoditization of the personal computer and thought through its implications. Then they developed a vision for the industry a decade out, in 2010, and asserted the new role that Apple could play in it. Instead of a stand-alone product, the Mac would sit at the center of an expanding “digital hub” of new devices and applications.

Then they brought that vision to life, hiring talent, developing software solutions, securing intellectual property, buying up relevant companies and technologies, and building new supply chains. The iPod launched in 2001, iTunes in 2003, and then the iPhone in 2007. The iPhone wasn’t just a new phone; it was a microcomputer plugged into a powerful ecosystem. It quickly proved that the cell phone companies had been playing the wrong game.

Starting from the future and working its way back, Apple created a powerful and comprehensive vision, and paired it with a strategy to bring it to life, while the incumbent cell phone giants took today’s knowns and projected them forward. While that present-forward mindset and the strategic and operational capabilities that go with it are entirely appropriate for maximizing existing opportunities and fending off traditional competitors, they are entirely inappropriate for launching products in a new category or navigating disruptive change.

The key point — underscored across our decades of research and practice on the management of disruption — is that technologies don’t replace technologies; systems replace systems. You can’t drop a product with a fundamentally new performance profile into an existing business model and expect it to work. The business model, how value is created, captured, and delivered, must be reinvented to support the new proposition, and business models must be reinvented from the future back.

BUILD TOWARD YOUR IDEAL END STATE

So, what does this mean for biopharma leaders who are assessing and developing cell, gene, and tissue-based therapies? First and foremost, you don’t want to be the next Nokia. Developing novel therapeutic classes within existing R&D and commercial strategy models is likely to blunt or negate their transformational potential. Instead, leaders should match their innovative scientific and technical efforts with equally innovative business model and market development efforts.

The first strategic question they must ask themselves is whether the envisioned platforms fit within their current conceptions of the industry. Will value still be created, captured, and delivered as it is today, or will the new technologies spur a realignment?

We don’t pretend to have a crystal ball; some therapies that leverage novel modalities may work just fine within existing structures, just as smarter cell phones were indeed better phones. But we all know that today’s model is stretched to the breaking point, particularly when it comes to patient compliance, physician incentives, and drug pricing. Many of the therapies enabled by novel modalities will push on these tension points; they are intended to be curative and would be dosed infrequently (some even just once). They would require new patient behaviors, ask physicians to do new things, and they are likely to feature multimillion-dollar price tags. Furthermore, they will have distinct manufacturing, distribution, and evidence-generation requirements. The point is that you can’t increment from today’s system to tomorrow’s. Just as you do in R&D with the product itself, you must envision an ideal end state and then systematically build toward it.

Spark Therapeutics, acquired by Roche for $4.3 billion, has taken steps in this direction. With the aim of priming the entire healthcare ecosystem for Luxturna, they engaged patients, providers, and payers early on, innovating services and solutions around their therapy. “Generation Patient Services” helps candidates for Luxturna navigate the journey from confirmed diagnosis to postprocedure follow-up, providing answers to their questions about insurance coverage and financial assistance. To ensure that providers get the training they need, Spark helped set up preapproved Ocular Gene Therapy Treatment Centers. And they developed novel contracting mechanisms with payers, to enable outcomes-based models.

The key to sustained success for laudable initiatives like these is they can’t just be features and tactics added on to an existing model; that would be equivalent to a calendar app on an early smartphone. Rather, they should be part of a systematic plan to shape the ecosystem of tomorrow, reflecting the new and different game that the biopharma industry will be playing.

MARK JOHNSON is cofounder and a senior partner and JOSH SUSKEWICZ is a partner at Innosight, a strategy and innovation consulting firm. They are authors of Lead from the Future: How to Turn Visionary Thinking Into Breakthrough Growth. XIAOXING WANG is a senior associate at Innosight.