AbbVie Goes All-In On Wearables And Digital Technologies

By Ed Miseta, Chief Editor, Clinical Leader

When working groups at AbbVie first began evaluating the use of digital technologies in clinical trials, the discussions were mostly conceptual. Individuals agonized over the right approach, the quality of the data, and whether the efforts would be accepted by regulators. Those discussions seemed to lead to more questions than answers.

Three years ago, we decided to stop debating and start executing,” says Rob Scott, M.D., chief medical officer and VP of development for AbbVie. “We made the decision to place wearables in three clinical trials. The reasoning behind this effort was quite simple. The potential benefits for patients are so great that we felt we had to replace manual, traditional clinical trial techniques with digital solutions.”

At the time, AbbVie had parallel goals. The company wanted to deploy digital technologies but also wanted to improve the way it designed clinical trials to make them more data-driven. A center of excellence was created for clinical trial design that focused on using large data sets. Its purpose was to help teams visualize the required patient population, the impact of their design decisions on patients, and the expected impact of geography and epidemiology.

“At that point we decided to create the Development Design Center (DDC),” says Scott. “We brought in a technology package called Infosario (now known as IQVIA Design), which is a platform that enables clients to leverage data for improved collaboration and decision-making.”

USE WEARABLES TO TRACK ACTIVITY

AbbVie ran three pilot projects with wearables that worked out well. One trial was conducted using the Philips Actigraphy watch to measure sleep quality and itching in patients with atopic dermatitis. AbbVie plans to implement this new technology as part of Phase 3 trials.

The company also used wearable devices in a trial for patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease. In the trial, gait and sleep were measured, which Scott says are particularly difficult to measure using traditional methods with pen and paper. For this trial, patients wore a sensor on their arm and leg that continuously and objectively measured Parkinson motor symptoms.

“These activity devices measured movement at the wrist and ankle,” says Scott. “This enabled us to detect whether the patient was having a tremor. For example, over a 24-hour period, using a set dosage, we could determine what percent of the time patients were in control of their symptoms. An algorithm also enabled researchers to determine whether patients had a good gait, or if the Parkinson’s drug would lose effectiveness as patients got to the end of the dosing interval. The devices helped researchers determine how well a patient was sleeping; we know that sleep quality for Parkinson’s disease patients has a big effect on their quality of life. If patients have poor sleep quality because their drug is not as effective at night, they will feel bad during the day.”

The wrist and ankle activity trackers were used in an initial pilot study. AbbVie has now replaced those devices with a wireless patch worn on an arm and leg. The patches are more comfortable and less intrusive for patients.

A third trial used a Fitbit to measure activity levels as a measure of increased quality of life.

KEY LEARNINGS & NEXT-GEN DIGITAL TRIALS

There were some key takeaways in those early days of using digital technologies in clinical trials. For example, every time patients visited the clinic, someone had to verify they were actually using the devices and collecting the required data. There also had to be a data download performed at that time. While the task is not difficult, site personnel simply did not have the experience necessary to perform it properly. Scott describes the activity devices as being large and clunky, and the skin on patients with atopic dermatitis would get irritated by them. As a result, some patients simply decided to stop wearing them.

![]() "We recognize that past performance is only a modest predictor of future performance. An artificial intelligence-driven model could help us do a much better job of predicting what actual site performance will be."

"We recognize that past performance is only a modest predictor of future performance. An artificial intelligence-driven model could help us do a much better job of predicting what actual site performance will be."

ROB SCOTT, M.D.

chief medical officer and VP of development, AbbVie

Another key learning was that a lot more had to be done to drive the digital culture at AbbVie. “I like to tell people it is OK to make mistakes and to fail. What’s important is that we learn from those situations and quickly evolve,” Scott says.

Today, every study team at AbbVie must consider a digital strategy in their planning. The company also created the position of digital valet. Implemented in the DDC, this person will lead teams through the process of introducing digital technologies into clinical trials. The digital valet AbbVie recruited had experience in designing and engineering devices, qualifying them, and deploying them in clinical trials.

THE EFFECTS OF DEVICE FORM FACTOR

Today’s wearables can collect huge volumes of data. For example, one device can collect movement data several hundred times a second, which produces an enormous data set.

But the ability to access that data varies depending upon the type of device used. Consumer-grade devices are more user-friendly, but the data they provide has already been processed through an algorithm and is often limited (e.g., only time can be tracked). Medical-grade devices, on the other hand, are large and clunky but provide the raw data AbbVie requires.

“There are definite trade-offs between these devices,” says Scott. “If we had used an Apple watch, which also collects activity data, the patients might have found it more engaging and may have opted to wear it more often. The Philips watch was medical-grade, and that was the value we saw in using it.”

HELP FOR PATIENTS AND SITES

AbbVie also has been working on the implementation of patient-engagement apps. These apps will facilitate patient involvement in clinical trials by offering support such as appointment and medication-adherence reminders. The apps also will tell patients what will happen during a visit and what, if anything, they need to do to prepare for a visit (e.g., fasting). A similar app is being used for sites.

According to Scott, there are now 60 digital initiatives underway at AbbVie. All of these efforts fall into six distinct categories. The first one is the use of social media and web platforms. In this area, AbbVie hopes to garner patient insights about their disease journey and their clinical trial journey. Social media also can help AbbVie by providing feedback on the feasibility of the study. Simply making patients aware of clinical trials is another goal.

The second is the use of predictive analytics to perform protocol design. Identifying sites and patients is one of the primary goals of this initiative. “We are working to answer questions about patient populations by accessing information in the electronic medical records of 50 million patients,” says Scott. “When we sit down to design a clinical trial, we can produce the inclusion and exclusion criteria and run it through the cohort. By doing so, we can see how many patients are actually enrollable. By tweaking the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we can see how much harder or easier it will be to enroll patients.”

AUTOMATION AND VIRTUAL TRIALS

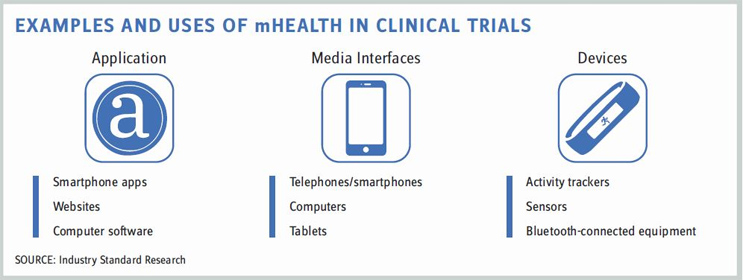

The third category of the six is wearables, sensors, and connected clinical devices, which enable remote and continuous monitoring, passive data collection, digital endpoints and biomarkers, drug supply tracking, and medication adherence.

The fourth is mobile applications, which will help patients find trials, track progress, and adhere to their medications. Mobile applications will allow reminders and notifications to be sent. Scott also places eConsent, ePRO (electronic patient reported outcomes), and eCOA (electronic clinical outcome assessment) in this category.

The fifth category is AbbVie’s own internal e-clinical systems. The company is trying to replace many manual tasks with automated solutions. Two efforts currently underway are risk-based monitoring (RBM) and electronic consent forms. AbbVie is also exploring the use of eSource. This technology will enable the company to access patient records remotely, as opposed to visiting a site to monitor the database and patient records. Payments and drug supply are two other areas AbbVie is hoping to automate. The storing, handling, transporting, and distributing of drug products are all areas where automation can provide benefits.

Another area where automation is expected to help is in predicting site performance. “We used to look at past enrollment to predict how well a site would perform in the future,” says Scott. “Of course, we recognize that past performance is only a modest predictor of future performance. An artificial intelligence-driven model could help us do a much better job of predicting what actual site performance will be.”

The final category, which Scott believes will be a game changer, is the concept of telemedicine and virtual clinical trials. This concept involves patients being able to participate in a trial without having to physically visit an investigator site. The average patient travels over 50 miles to visit a site, and 70 percent of patients that would like to take part in a trial can’t do so because of travel distance. What if there was a virtual trial model that includes traditional sites but also virtual patients who continue to see their own physician? Those patients will then interact with the site through telemedicine.

“Some patients prefer to participate in trials via online sites, and others still prefer to visit the brick-and-mortar sites. Some want a combination of both. We think the hybrid model we’re developing will provide patients with the options they desire.”

WORK WITH REGULATORS

During our almost one-hour discussion, Scott barely mentioned the word “regulators” when discussing wearable devices. He personally believes regulators are very interested in digital health and want to help drive innovation in clinical trials.

“I have found regulators are very open to advances in this area,” he says. “They want to be convinced that what we are doing is robust and meaningful, but that is simply part of their job.”

Scott certainly sees a bright future for digital technologies. He believes that in just 10 years, clinical development is going to look very different. One major change will be trials becoming less labor-intensive for sponsors. More data will be collected passively. Usable data will be extracted from electronic medical records, but trial data also will be impacted by the Internet of Things. Connected devices will enable researchers to gather data without any requirement for manual data entry.

“Digital strategies will evolve, as well,” adds Scott. “Every clinical team will have its own digital strategy. They will test the digital techniques for usability in Phase 1, roll them out and validate them in Phase 2, use them in Phase 3, and incorporate them into product labels. That will enable pharma companies to adopt different business models while getting new and better treatments to patients faster.”

"We recognize that past performance is only a modest predictor of future performance. An artificial intelligence-driven model could help us do a much better job of predicting what actual site performance will be."

"We recognize that past performance is only a modest predictor of future performance. An artificial intelligence-driven model could help us do a much better job of predicting what actual site performance will be."