Can We Make Innovative Medicines Affordable?

By Rob Wright, Chief Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @RfwrightLSL

An Insightful Discussion On Drug Pricing – Part 1

“As the price of pharmaceuticals continues to rise, we are seeing greater resistance from [U.S.] patients being willing to pay,” says Dr. Steven Miller. The SVP and chief medical officer at Express Scripts is giving his opening remarks during the Our Common Goal: Ensuring Access and Affordability of Innovative Medicines session at the 2017 BIO International Convention in San Diego. Miller pulls no punches with his fellow biopharmaceutical executive panelists, setting the tone that today’s discussion on drug pricing will not be a “hugfest.”

Billed as a one of the “can’t miss educational sessions for BIO 2017,” panelists included an insurance industry executive (Steven Miller, M.D.), two biopharmaceutical industry executives (Jeremy Levin, D.Phil, MB BChir, CEO of Ovid Therapeutics and David Meeker, M.D., former EVP of Sanofi Genzyme) and one executive who spanned biopharma, retail pharmacy, drug distribution, and insurance (Jeffrey Berkowitz, formerly EVP at Merck, Walgreens Boots Alliance, and UnitedHealth Group). Actually there were three biopharma execs if you include the moderator, Ron Cohen, M.D., CEO of Acorda Therapeutics. As three of the five participated in a special drug pricing roundtable published in Life Science Leader’s July 2016 issue, it seemed like a great opportunity to provide an update on this seemingly ever-controversial topic — which we will do in two parts.

Billed as a one of the “can’t miss educational sessions for BIO 2017,” panelists included an insurance industry executive (Steven Miller, M.D.), two biopharmaceutical industry executives (Jeremy Levin, D.Phil, MB BChir, CEO of Ovid Therapeutics and David Meeker, M.D., former EVP of Sanofi Genzyme) and one executive who spanned biopharma, retail pharmacy, drug distribution, and insurance (Jeffrey Berkowitz, formerly EVP at Merck, Walgreens Boots Alliance, and UnitedHealth Group). Actually there were three biopharma execs if you include the moderator, Ron Cohen, M.D., CEO of Acorda Therapeutics. As three of the five participated in a special drug pricing roundtable published in Life Science Leader’s July 2016 issue, it seemed like a great opportunity to provide an update on this seemingly ever-controversial topic — which we will do in two parts.

COHEN: In the U.S., we struggle to achieve a balance between allowing biopharma to continue to accelerate as an innovation machine, while at the same time, figuring out how the system can best pay for these goods and services, which are often more costly when compared to the rest of the world. Each panelist will now provide an introductory statement.

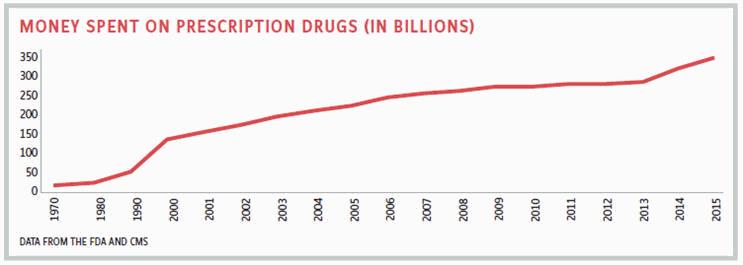

MILLER: America represents 4.6 percent of the world’s population, yet takes about 33 percent of drugs by dollar volume and represents between 50 and 70 percent of the pharmaceutical industry’s profitability. For a long time, the U.S. has been funding medical innovation for the world. But as the price of pharmaceuticals continues to rise, we are seeing greater resistance from patients being willing to pay. This resistance is driven, in part, by the U.S. having higher-priced drugs as compared to the rest of the world, and more people being subjected to incredible out-of-pocket payments. For the most part, high-deductible health plans are designed for rich people, yet are most often sold to poor people. And when a poor patient with such a plan goes to pick up their medication and learns they will have a high outof- pocket payment, they often end up leaving it at the pharmacy. So all the great things the biopharma industry is inventing aren’t getting to those who need them.

BERKOWITZ: The drug pricing problem isn’t going to be solved by biopharma continuing to work on extremely important science without engaging other key healthcare ecosystem stakeholders. Though there has been a significant consolidation, we continue to reside in a world where many healthcare industry stakeholders are talking at each other. Biopharma needs to do a better job engaging with the rest of the healthcare ecosystem regarding what they are working on, and the rest of the healthcare ecosystem (i.e., insurance payers, providers, PBMs, and retail pharmacies) need to improve their level of engagement with one another. Finally, there needs to be accountability at the highest levels of biopharma organizations to better understand where and if their products fit commercially in a consolidating marketplace.

LEVIN: As the CEO of a biopharma company, it is my job to see what I can do to improve our healthcare ecosystem. I do not believe presidential orders, congressional oversight, or massive policy changes are at the core of what is necessary to correct the current drug pricing issue. However, I do believe certain aspects of our healthcare system and industry can be changed to impact pricing and unacceptable patterns of price rises, and to do that all healthcare industry leaders need to step forward, a process which begins with how they approach leading their own organizations.

MEEKER: The challenge isn’t the process of innovation, but how to get these innovations to the individual patient (i.e., access and affordability) most efficiently. If we work backwards from that, we will find the necessary savings in our relatively inefficient healthcare system to allow that to happen. But you can’t have one stakeholder working individually toward solving the problem. Viable solutions require a holistic and collective approach involving all stakeholders being willing to give on their own points of inefficiency.

COHEN: In addition to patients not being able to afford their co-pays or coinsurance, sometimes they can’t get their prescription because the insurance company or PBM imposes certain step edits or prior authorizations on the physician to prescribe a given medication. To this we can add PBMs blaming drug companies for high drug prices, and drug companies highlighting PBMs accepting big rebates that don’t specifically help the patient afford their prescription. So how do we address this situation?

MILLER: Manufacturers use rebates to either reward or punish. For example, if a PBM puts a drug on its formulary, manufacturers give the PBM a discount via a rebate. If a PBM doesn’t put the manufacturer’s drug on its formulary but instead puts a competitor’s drug on its formulary, they punish the PBM by charging it more, giving less or no rebate at all. PBMs benefit from getting higher rebates because they take a percent of that rebate, which helps achieve the goal of selling drugs at the lowest net cost. The U.S. drug rebate system, with all of its pros and cons, is a legislated legal requirement by government for Medicare and, as such, won’t be going away anytime soon. That being said, PBMs are working to make drug pricing more transparent for patients. For example, Express Scripts developed a program called InsideRx to offer lower rates for select groups of frequently used drugs. The program was designed for patients without insurance or those with high-deductible insurance plans, as these people were the only ones paying list price. Consumers can sign up for free and, if they qualify, use a discount card or mobile app to get a rebate at the point of sale. Essentially, we are jury-rigging a maladaptive system.

BERKOWITZ: Jury-rigging is a good way to put it, because we still operate in a traditional system that hasn’t changed. I find it remarkable that members of the healthcare ecosystem put very little thought into figuring out how to best get a new drug into a patient’s hand. It isn’t until maybe three to six months prior to a new drug’s launch/approval that biopharmas begin meeting with PBMs. Yet, for PBMs to understand the science and the problem a biopharma’s innovation is trying to solve, engagement needs to begin earlier. There has been so much consolidation and integration that there are only a few conversations needed between a biopharma company and other industry stakeholders. Today in the U.S., there are about five national health plans, two retail pharmacy chains, three PBMs, and three specialty pharmacies that really matter. Biopharma having conversations with these stakeholders at the earliest stages should provide enough information to help make more informed drug pricing and reimbursement decisions.

LEVIN: It is interesting to hear the description from Jeff of the small handful of players with which biopharma companies need to engage. However, one cannot underestimate the impact that both the lack of training or the access to employees in biopharma companies who understand or can initiate the necessary dialogue on the biopharma side for this “earlier engagement.” For large companies that might have many people working on access with key healthcare industry stakeholders, this dialogue is relatively straightforward. But the majority of small biopharma companies where innovation is the primary focus of investment simply don’t have the resources necessary to have those meaningful discussions, let alone know who to go to talk with or often why it’s important to engage early. Generic companies understand access well as they deal with huge volumes and multiple drugs. These companies meet routinely with payors, pharmacy chains, and PBMs, often at selected venues and conferences. For large branded biopharma companies, the system of access is focused on individual innovative products.

MEEKER: You mentioned the jury-rigging part of this. Is that the only way forward? Are we resigned to only being able to make small, incremental steps to address the drug-pricing patient-access problem?

MILLER: We are at an inflection point as we move away from a pricing model built on volume and toward one built on value. Value-based contracting has actually required people from biopharma and insurance to start engaging, because it’s not just a transaction (i.e., put my drug on formulary, and I’ll give you a rebate). For example, when Regeneron and Sanofi were bringing dupilumab (a new treatment for adults with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe eczema) to market, they went on a listening tour with everyone Jeffrey Berkowitz just described. The companies wanted to have a deep understanding of reimbursement and understand our pain points. This helped Express Scripts better understand their pain points, as well as how the drug was going to work. If you look at the results, Regeneron and Sanofi brought dupilumab out at an incredibly reasonable price (i.e., $37,000). While not cheap, when compared to another psoriasis treatment costing $65,000, it’s nearly half-price. The companies even received a positive response from a review by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). Express Scripts has since had similar positive experiences with Genentech’s new MS product, OCREVUS (ocrelizumab), and Radius Health’s osteoporosis drug, TYMLOS (abaloparatide). What I just described is what the future needs if we hope to create a sustainable business model.

LEVIN: There will be a moment where for all medicines an understanding of what is a meaningful medical impact will have to be established in order to incorporate value into the pricing model. For example, one of the disorders my company works on is Angelman syndrome. A mother of a child with Angelman syndrome will tell you that a “meaningful difference” in their child is their having the ability to better communicate. Most children with Angelman syndrome suffer from a number of disabling conditions including cognitive problems, epilepsy, and insomnia, and many don’t easily communicate verbally. Some have learned to use a few signs of American Sign Language (ASL). For the parent of a child who uses just one sign, learning two will be a tremendous benefit. In those families, the same sign is used to tell the caregiver or parent they need water, want to sleep, etc. But if the child could, following treatment with a medicine, suddenly have two signs, suddenly these children are able to communicate much more clearly. So the concept of meaningful impact and therefore value of a drug will need to be better understood by the payor, the regulators, and the system taking care of the patients and, in doing so, incorporated into the pricing model.

MILLER: Such education has to start much earlier and requires repetition. Biopharmas need to be meeting with other healthcare ecosystem stakeholders two years before the product is in the pipeline, and you will need to come back throughout the process. Only over time will we together figure out if a payer is actually going to reimburse for that “meaningful” difference.

COHEN: Let me go back to the question: “Are drugs too expensive?” But for this discussion, let’s leave aside drug price increases for products that are already on the market.

MEEKER: The classic statistic of drugs representing only 14 percent of the total healthcare spend has been relatively stable over time and, as a percentage, does not differ greatly around the globe. The issue isn’t whether we are spending too much on drugs in the aggregate, because that 14 percent figure includes 90 percent of prescriptions filled by generics. The question is: Are drugs too expensive for any given individual? I would love a system where I can get a fair price for those people who can afford to pay for it, and for those who can’t or fall outside of the system, I would be happy to give the drug away for free.

BERKOWITZ: But with that approach, you are still jury-rigging the system (i.e., robbing from Peter to pay Paul). It’s not so much that drugs across the board are expensive, but are you looking at a particular therapeutic class, and a particular need of a particular product, at a particular point in time as a drug is launched. Dupilumab is an example of a product brought to a market that was understood with regard to expenses and pain points. The company had a solution that provided a different outcome of value for the system and the patient and believed they would be reimbursed if it was priced a certain way.

COHEN: I’m going to posit that if Regeneron and Sanofi came out with a $37,000 price tag for this drug back in 1980, everyone would have completely lost their marbles.

MILLER: That happened when Genzyme developed an enzyme replacement therapy that was priced at $300,000. However, the company never raised the price. A stable drug price that doesn’t increase from when it was launched is what actually happens in almost every other country. When drug companies launch a new drug and announce what the launch price is, they theoretically calculated in what was needed from a return on investment perspective. Only in America do we see cases where drugs are launched at one price, and then price increases are taken over the years. For example, Gleevec was launched at $30,000 a year, yet it went up to over $100,000. Viagra came out at $7 a tablet, and yet it went up to around $50. These are two drugs with zero rebates, so the price increases can’t be blamed on anyone but the manufacturer. If you ask the average American consumer, “Are drugs too expensive?” Yes. Does the pharma industry deserve a percent of GDP forever? Absolutely not. This idea that biopharma is and always will be only 14 percent of healthcare costs is a fallacy. Every aspect of healthcare in America is more expensive than it is in the rest of the world, and our results are not as good as other Western countries.

LEVIN: I helped launched Ceredase, the $300,000 drug and, like all involved, take great pride in the fact that Henri Termeer never increased the price, and yet the drug was accessed by a tremendous number of those Gauchers patients who needed it. This shows us that it’s not the just the initial price that is central to the issue, but rather the subsequent price increases that are the problem. Many of these rises are unconscionable because there is no change in the effect of the drug and often no label expansion or investment to show additional benefits. This is something that the industry can actually do something about. The insulin patent was sold to the University of Toronto by Banting, Best, and Collip for three Canadian dollars in 1921 with the explicit hope that diabetics could have affordable insulin forever. This has not been the case, and prices have risen consistently and sometimes very significantly even for the older, unpatented forms of insulin. How do we address this? For starters, companies can take a stand by not rewarding executives through cancelling incentive compensation for price increases. Every biopharma compensation committee on every corporate board can review how their CEO and senior management are compensated and can create systems that incent innovation and not incentivize or even, where possible, disincentivize, price increases. Companies focused on price rises tend not to focus on innovation. But it is innovation that drives a sustainable industry.

MEEKER: Unfortunately, the Shkreli example, which is an outlier, has become the poster child for the drug-price-increase problem. The bigger issue is the 10 to 20 percent price increases that get taken on a yearly basis to meet earnings. These are what are going to break the system. My biggest concern is that absent industry self-regulation, we will be regulated, and if we are regulated, the market forces and the incentives that have allowed the U.S. biopharma system to exist will end, as will the innovative R&D. Industry needs to step in and be a part of fixing this, and our efforts need to be more visible. At Sanofi we made a statement that we were not going to take price increases greater than the national health expenditure, which was 5 percent last year. That statement came out of internal drug-price increase dialogue that began six years ago. As an industry, I hope we can give such self-managed initiatives a chance to work. When we brought Kevzara [an anti-IL 6 antibody] out, it was second to market. As such, we wanted to launch it at a price that was significantly lower than some of the alternatives. But our pricing efforts were handcuffed by a system that had contracts in place that were very difficult to unwind. So my question to Steve Miller and Jeff Berkowitz is: How do we move from where we are to a new world that allows examples like the pricing of Kevzara to happen?

Though we must pause our most insightful drug-pricing discussion here, David Meeker’s thought-provoking question primes the conversation to continue next month in, “Making Innovative Medicines Affordable: Concluding An Insightful Drug-Pricing Discussion — Part 2.”