Closing The Presubmission Communication Gap Between Drug Developers And The FDA

Ron Farkas is VP, technical, and Alberto Grignolo is corporate VP at PAREXEL

By Ron Farkas and Alberto Grignolo

There’s no doubting the tremendous benefits that can be gained from meetings between FDA staff and sponsors during drug development. If everyone can agree on critical aspects of a development program (for instance, trial designs and endpoints) early in the process, drugs can be developed more efficiently, and everybody wins.

But problems can arise from the parties’ differing aims.

Sponsors would like guidance — and, preferably, certainty — on which development program features will make their results acceptable to FDA reviewers (in the form of an approved marketing application). Much is discussed in these meetings, but sponsors are primarily looking for what they must do to achieve regulatory approval. Major investments of money, labor, and time are at stake, as are the returns on those investments.

On the other side of the table, FDA regulators generally view presubmission meetings, and other interactions with sponsors, as opportunities to brainstorm, head off “bad” ideas, or warn sponsors about potential pitfalls. They may shy away from providing absolute clarity between “nice-to-haves” and “must-haves” in the hope that sponsors will attend to the broadest possible range of issues that could impact their development plan.

The misunderstandings that arise from the sponsors’ and regulators’ differing agendas and expectations in these meetings may not only defeat their purpose, but they can drive developers to make the wrong decisions for the wrong reasons. For example, a regulator’s warnings about a potential pitfall in a development plan can be interpreted by a sponsor as a flat-out rejection.

It’s a truism that the answer to many complex questions in drug development is “it depends” rather than “yes” or “no”. But because sponsors expect FDA feedback to be clear and definite (neither “it depends” nor “yes, but…”), the FDA’s answer to a yes/no question is more likely to be “no” for the simple reason that anything less than 100 percent agreement is, technically, a “no”, whether the level of disagreement is major or minor. “No” may also be directed at what the FDA can see as the sponsor’s over-optimism, for example expecting a large beneficial effect, or asserting that a drug is without potential safety risks. Thus, sometimes, even when the technical disagreement is relatively small and unlikely to be a threat to approval , the FDA may be unwilling to say unequivocally “yes” because it wants its concerns heard and duly considered by the sponsor.

Both regulators and sponsors bear responsibility for saying what they mean, and interpreting correctly what’s being said. However, in a dynamic interaction, with so much riding on the outcome, this is not always simple. A solution to a potential impasse in these situations is to adopt a more nuanced approach based on a benefit-risk framework and discussion.

A Framework Could Help Both Sides Say What They Mean, And Hear What’s Being Said

The FDA’s “Structured Approach to Benefit-Risk Assessment in Drug Regulatory Decision-Making” was designed to provide transparency about risk-benefit calculations made during the formal review of new drug applications. It does so by summarizing “the relevant facts, uncertainties, and key areas of judgment” and explains “how these factors influence a regulatory decision.”

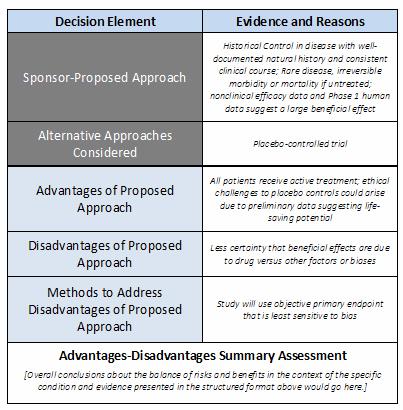

Sponsors could get more out of presubmission meetings if they used a similarly structured “Advantages-Disadvantages” framework to map the decision space around important development questions (Table 1) and FDA responses. Such a decision grid could help avoid the temptation to look for binary answers (e.g. “good” idea vs “bad” idea) where there aren’t any, and gain a clearer understanding of the benefits and risks of different development paths.

Table 1. Example of a Simple “Advantages-Disadvantages” Framework to Guide Discussions About Use of a Historical Control in a Pivotal Clinical Trial

Table 1 shows a hypothetical example of how a sponsor might fill out the Advantages-Disadvantages Framework in preparation for a meeting with FDA staff. In this case, the arguments are for use of a historical control arm in a pivotal clinical trial.

Filling in the framework’s fields prompts sponsors to:

- Declare the approach they think best (primary endpoint or control arm)

- List reasonable alternatives

- Explain why their proposed approach is preferable (it saves time or allows every patient to receive an experimental drug)

- Delineate the potential shortcomings of their proposed approach

Framing the discussion this way assures regulators that the sponsor has done the homework — not only to justify the proposed approach, but to rank it higher than other options and manage its risks. A framework promotes a healthy discussion and avoids forcing regulators into a No response..

Advice is Nice, But Sponsors Must Make — and Defend — Their Own Decisions

Regulators’ responses tend to be conservative and risk-averse. That’s the safest course when a sponsor’s argument is in some way deficient, has risks, or there is not enough time for the sponsor to properly explain its rationale. Unfortunately, when sponsors misinterpret or over-interpret FDA comments they can pay a heavy price in time and money.

It’s critical to remember that the NDA/BLA development meetings are a discussion, not a decision. If sponsors hear a No, they should make sure they understand why. The regulator’s objection might not be insurmountable. And when receiving FDA advice, failing to follow it will not always lead to NDA/BLA rejection. The development of a drug is the sponsor’s responsibility. That means making and justifying decisions that are scientifically sound and pragmatic in the real world.

Drug developers must make thoughtful judgments and take calculated risks. That’s best done by carefully considering the advantages and disadvantages of every option, both with and without FDA advice. Having a framework does precisely that, and helps close the communication gap with regulators.

Ron Farkas is VP, technical, and Alberto Grignolo is corporate VP at PAREXEL