Countering Provider Consolidation

By John McManus, The McManus Group

As Congress debates partisan issues such as “Medicare for All” where private health insurance would be outlawed, troubling trends are emerging on healthcare provider consolidation that are driving up costs.

As Congress debates partisan issues such as “Medicare for All” where private health insurance would be outlawed, troubling trends are emerging on healthcare provider consolidation that are driving up costs.

ACOs’ Underwhelming Performance

There is a long-standing belief — particularly in liberal and academic health-policy circles — that physician–hospital integration into larger systems would improve quality of care and bring cost efficiencies. That’s why the then-Democratic Congress created “accountable care organizations” (ACOs) — mostly hospital-led megasystems in the Affordable Care Act. There are now more than 500 such organizations, serving over 10 million Medicare beneficiaries.

How have ACOs fared in delivering lower costs? Poorly.

Harold Miller, president of Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, analyzed CMS’s August 2018 data dump on ACOs participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. He discovered that in 2017, CMS gave nearly $800 million back in bonuses to the 472 ACOs that had spent $1.1 billion less than the benchmark target. It had collected only $57 million in penalties from the 16 ACOs engaged in two-sided risk programs who had missed their targets, netting a grand total of $317 million or about $36 per beneficiary (0.33 percent of total spending) for 2017. Moreover, the ACO program had lost $384 million in the first four years of existence, meaning it “had yet to generate a net benefit to Medicare after five years of trying.”

Provider Consolidation Acceleration = More Costs

But ACOs have helped accelerate provider consolidation as independent, specialty practices are threatened with being frozen out of referrals if they don’t team up with dominant hospitals.

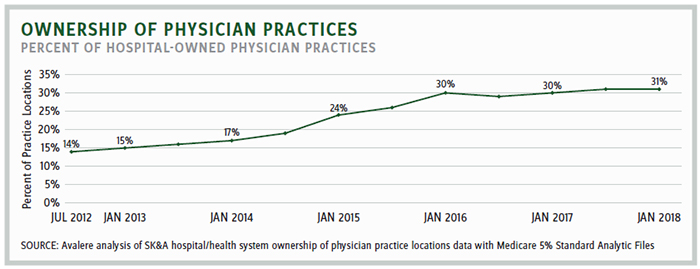

A recent study by Avalere for the Physician Advocacy Institute found that the percentage of hospital-employed physicians increased by more than 70 percent from July 2012 through January 2018. In just the last two years, an additional 8,000 physician practices were acquired by hospitals. From July 2012 through January 2018, hospital acquisitions of physician practices more than doubled, with nearly one-third now owned by hospitals.

Why should this be of concern to policymakers? Hospitals cost a lot more than physician practices, even when delivering the identical items and services.

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) March 2018 report found that from 2011 to 2016, program spending and beneficiary cost-sharing on services covered under hospital outpatient departments increased by 51 percent, from $39.8 billion to $60 billion. MedPAC noted, ‘‘A large source of growth in spending on services furnished in hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) appears to be the result of the unnecessary shift of services from (lower-cost) physician offices to (higher-cost) HOPDs.”

In a February letter to the bipartisan congressional leadership, the Alliance for Site Neutral Payment Reform — a coalition of healthcare providers and insurers — documented vast differences in Medicare payments of specific services when they are delivered in hospital outpatient departments versus physician offices and ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs). For example, “chemotherapy: $281 versus $136; cardiac imaging: $2,078 versus $655; and colonoscopy $1,383 versus $625.”

There is no clinical reason that nearly half of the 2.7 million annual colonoscopies paid by Medicare continue to be performed in the more expensive hospital setting. Most can be performed conveniently and effectively in ASCs in the community.

Analogous results were observed on the commercial side: A University of California, Berkeley study that reviewed 4.5 million commercial HMO enrollees found hospital-owned organizations incurred 19.8 percent higher expenditures than physician-owned organizations for professional, hospital, laboratory, and pharmacy services.

Moreover, hospital prices are growing substantially faster than physician prices for hospital-based care. A recent Health Affairs study examined price increases between 2007 and 2014:

- Hospital prices for hospital outpatient care grew 25 percent, while physician prices only grew 6 percent, and for inpatient care, hospital prices grew 42 percent while physician prices only grew 18 percent.

- A majority of the growth in payments for inpatient and hospital-based outpatient care was driven by growth in hospital prices, not physician prices.

Congress attempted to arrest this consolidation when it enacted the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, which prevented hospitals from charging Medicare their higher prices for physician practices and ASCs acquired after enactment. But that policy is focused primarily on evaluation and management visits, not surgery or

drug infusions.

CMS recently expanded its interpretation of this law to apply to other services in newly acquired physician practices, citing its authority for controlling “unnecessary” increases in the volume of covered outpatient department (OPD) services. However, the American Hospital Association and other hospital groups have sued to block this interpretation, arguing that CMS has exceeded its authority. That process is still unfolding.

That lawsuit is analogous to successful litigation the hospital industry prevailed on in December 2018 in district court with respect to Medicare cuts to 340B hospitals for statutorily discounted drugs. CMS had reduced Medicare payments to 340B hospitals from average sales price (ASP) plus 6 percent to ASP minus 22.5 percent. Hospitals are now trying to recoup back payments.

Potential Solution: Invigorate Independent Practices

Policymakers would like physician practices to do more to move from fee-for-service into value-based care. The Stark self-referral law prohibits physician practices from remunerating their doctors based on “volume or value,” even in the context of capitated arrangements that limit financial risks. Recognizing this barrier to coordinated care, the ACA granted the secretary the authority to waive the Stark law for ACOs. Yet independent practices were left behind: The Center of Medicare and Medicaid Innovation has not approved a single alternative payment model (APM) of the 26 reviewed by the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee.

The law needs to be modernized to encourage physician participation and success in APMs. Prohibitions on remuneration for “value or volume” make no sense under capitated or at-risk arrangements that seek to incentivize appropriate physician behavior for adherence to recognized treatment pathways. How can Medicare promote value-based care if physicians are explicitly prohibited from remunerating based on value in the statute?

Vibrant independent practices are needed as a competitive counterweight to mega hospital systems. Modernizing this law would do a lot to level the playing field.

A coalition of 25 physician organizations across the House of Medicine has endorsed bipartisan legislation to allow physician practices to test and participate in APMs without the antiquated restrictions of the Stark law. That is a solution that Congress can enact this year — leaving the larger battle of Medicare for All to election year politics in 2020.

John McManus is president and founder of The McManus Group, a consulting firm specializing in strategic policy and political counsel and advocacy for healthcare clients with issues before Congress and the administration. Prior to founding his firm, McManus served Chairman Bill Thomas as the staff director of the Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, where he led the policy development, negotiations, and drafting of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. Before working for Chairman Thomas, McManus worked for Eli Lilly & Company as a senior associate and for the Maryland House of Delegates as a research analyst. He earned his Master of Public Policy from Duke University and Bachelor of Arts from Washington and Lee University.