Diversity In The Biopharma Boardroom: Moving Past Good Intentions

By Christos Richards, partner, Catalyst Advisors

After years of being relegated down the governance agenda, diversity in the boardroom is now an acute optic and has become a priority for many biopharma companies. The focus on increasing the number of female and non-Caucasian directors continues even as biopharma boards are grappling with a tougher investor environment, unresolved pricing issues, and the uncertainty brought by the new Trump administration.

After years of being relegated down the governance agenda, diversity in the boardroom is now an acute optic and has become a priority for many biopharma companies. The focus on increasing the number of female and non-Caucasian directors continues even as biopharma boards are grappling with a tougher investor environment, unresolved pricing issues, and the uncertainty brought by the new Trump administration.

Though concerns such as these tend to push social responsibility initiatives to the back burner, the issue of boardroom diversity is now more than a societal imperative — it is an integral part of a best practices approach to corporate governance. It has been well established that diversity provides a hedge against groupthink, enriches debate, and helps lead to a more rigorous evaluation of risk.

With the board at the top of the organizational chart, diversity in the boardroom also has become a highly visible proxy for a company’s culture, increasing the company’s desirability as an employer. Smaller or earlier- stage companies once got a pass on this issue, but that exemption is evaporating given the competition for boardroom talent that all companies now face. A recent analysis by Catalyst Advisors and Atlas Ventures’ Bruce Booth suggested that biopharma firms, from startup to post-IPO, will need more than 600 new directors in the next several years — after having depleted the director candidate pool by adding 250 new directors in the past two years. The cold reality is that no biopharma company, large or small, can hope to succeed if it excludes, even inadvertently, any of the market’s executive talent from the candidate pool.

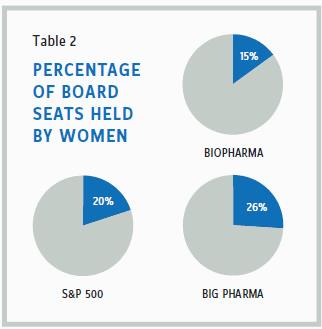

While it is only one aspect of the overall diversity landscape, gender diversity provides an easily quantifiable measure of equality of opportunity. Examining the board composition of the 164 publicly traded companies in the NASDAQ Biotechnology Index shows how much work remains to be done: As of the beginning of this year, only 15 percent of board members are women, and 26 percent of the companies in the index are still without a female director. In comparison, among S&P 500 companies, women hold 20 percent of board seats and 2 percent of those boards remain all-male; among the traditional Big Pharma companies, 26 percent of board seats are held by women and every board has at least one female director.

Organizations like Women in Bio and MassBio help keep a spotlight on gender diversity. Last year, Women in Bio announced a program to identify and provide boardroom training for female board-ready biopharma executives. While this year’s JP Morgan conference was taking place, MassBio released a letter signed by more than 100 biopharma leaders committed to implementing gender-diversity best practices, including asking current board members to act as active sponsors of women ready for their first board seat. But these initiatives beg the question of how it is that the industry’s good intentions on gender diversity have such difficulty being translated into reality.

HOW GOOD INTENTIONS FALL BY THE WAYSIDE

To answer that question, it is necessary to closely examine how the director search process typically unfolds. When looking to fill a board vacancy, nominating committees often start out eager to add a woman to the board’s roster. Once the recruiting process begins in earnest, however, many committees can fall back on default behaviors that prevent them from fully considering the complete talent pool available to them. Understanding how this happens will make it easier for nominating committees to fulfill their intentions for a more diverse boardroom.

In the heat of a search, it is not uncommon for nominating committees to become focused on pursuing a “name” director, such as the CEO who commands a well-known multibillion-dollar market-cap company. The common belief is that such an appointment will bring the board instant credibility with investors, a powerful professional network and the insight of knowing what it takes for an organization to reach the upper tiers of its industry.

The “name” director is, of course, the extreme case of the more general impulse to recruit a sitting CEO. But with only nine female CEOs in the NASDAQ Biotechnology Index, there simply aren’t enough female biopharma CEOs to go around. Of course, we need to increase the number of women who move into the CEO role — but that alone won’t appreciably improve the percentage of women biopharma directors. In addition, one must remember that regardless of the number of talented women who do move to the corner office, boards often restrict the number of outside board commitments their CEO may accept — a practice reinforced by recently issued ISS (Institutional Shareholder Services) guidelines.

SIDESTEPPING SELF-IMPOSED BOUNDARIES

Though the situation seems intractable, nominating committees can broaden their pool of female director candidates without compromising their standards if they are willing to rethink two long-held assumptions. The first is that only current or former CEOs — whether “names” or not — can make stellar directors. As Women in Bio and others have pointed out, the fact is that a great many executive committee members and business unit leaders have experience and judgment that would benefit the boards of biopharma companies preparing to scale operations and commercialize products. The business unit head who oversees a company revenue of half of a $20 billion market cap can certainly provide useful counsel to the CEO of a $1 billion company looking to lead that company into the next bracket. Non-CEO directors also tend to have less demanding travel schedules than CEOs, as well as fewer other obligations which might diminish outside boardroom bandwidth and availability. Indeed, the board that accepts a highly qualified regional president will be getting a director hungry to prove herself at the highest echelons of the industry. (It’s important to note that the due diligence on these candidates needs to include a thorough examination of potential conflicts of interest.)

The second assumption is that the technical nature of the industry largely limits the pool of directors to biopharma and traditional pharma. Even though board work is much more demanding and complex than it once was, it is still ultimately about advice and oversight rather than running the business. More importantly, purposely cross-pollinating and recruiting director candidates from among seasoned C-level executives in other industries may bring perspectives and experience that could greatly benefit a biopharma CEO while also increasing the pool of women under consideration. This strategy, however, is typically reserved for the more mature (and often commercial-stage) company, and is most fruitful if leveraged in specific disciplines such as finance, legal, and human resources.

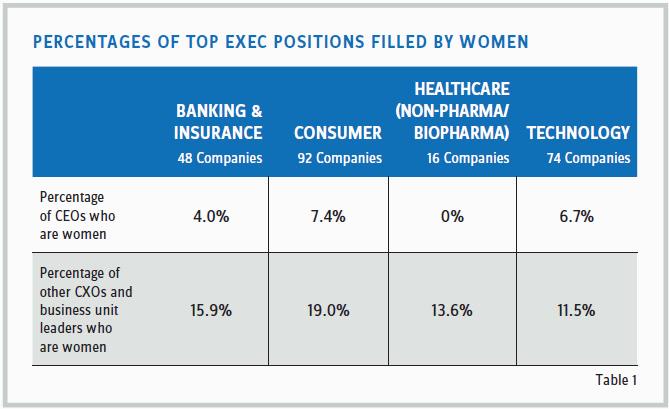

If we combine these two strategies — looking both deeper and wider — the pool of highly qualified female director candidates significantly expands. Table 1 shows how, across S&P 500 companies in four major industries, the percentage of women jumps when looking one level below the CEO. In absolute terms, these women represent an additional 610 potential director candidates.

In a recent engagement, for example, we were able to offer one biopharma client a gender-diverse slate of director finalists when we turned to executives from the reimbursement/managed care sector. In a current engagement, we are looking to the luxury goods sector to fill a board seat for a company developing an aesthetic therapy ultimately paid for by the consumer. Whomever the nominating committee ends up selecting, that choice will be all the stronger because it comes from a finalist slate that is diverse in both gender and experience.

GETTING TO YES

Updating the selection criteria is critical, but that is only half of what must be done for boards to successfully diversify. Boards must also position themselves to be attractive to female director candidates who are aggressively pursued by other boards, which will offer them competitive options. In addition to all the regular due diligence on the company’s leadership, finances, and science, boards should expect that female candidates will closely scrutinize the company’s track record on diversity in both the boardroom and within management. Companies currently operating without any female directors will find themselves in a challenging position on this score and will need to make a compelling argument regarding their commitment to diversity going forward, assuring female director candidates that the company isn’t simply putting a bandage on a deeper deficiency. The situation is similar to that of a board composed of investors and founders looking to bring on its first non-investor independent director. The most desirable candidates will want to ensure that though they may be “the first,” they won’t be “the only” indefinitely. And with good reason: Only after an underrepresented group reaches a critical mass — thought to be between 20 and 30 percent — can they begin to fully integrate into the larger group.

Updating the selection criteria is critical, but that is only half of what must be done for boards to successfully diversify. Boards must also position themselves to be attractive to female director candidates who are aggressively pursued by other boards, which will offer them competitive options. In addition to all the regular due diligence on the company’s leadership, finances, and science, boards should expect that female candidates will closely scrutinize the company’s track record on diversity in both the boardroom and within management. Companies currently operating without any female directors will find themselves in a challenging position on this score and will need to make a compelling argument regarding their commitment to diversity going forward, assuring female director candidates that the company isn’t simply putting a bandage on a deeper deficiency. The situation is similar to that of a board composed of investors and founders looking to bring on its first non-investor independent director. The most desirable candidates will want to ensure that though they may be “the first,” they won’t be “the only” indefinitely. And with good reason: Only after an underrepresented group reaches a critical mass — thought to be between 20 and 30 percent — can they begin to fully integrate into the larger group.

That more and more biopharma boards are making diversity a priority is another sign of the sector’s ongoing maturation. However, to make that priority a reality, biopharma nominating committees will have to broaden their approach to recruiting and be able to demonstrate their commitment to the diverse director candidates they hope to elect. Forward-thinking nominating committees will do these things even while the company is private so that a diversity orientation is hard-wired in from the start. Regardless of where a biopharma firm is in its trajectory, greater diversity in the boardroom will ensure that a company is better equipped to respond to its evolving challenges and opportunities.