Evolving Business Models: Pharmaceutical Incubators

By Lev Gerlovin, Jared Levine, Suneil Mendiratta

As pharmaceutical manufacturers grow, they often pursue external sources of innovation to supplement their own R&D efforts. A recent study found that 45% of drugs in the pipelines of 20 large biopharmaceutical companies were sourced externally in 2020. Sources of external innovation include M&A, university partnerships, licensing, joint ventures, and direct ownership investments. Over the past fifteen years, many large players in the industry have supplemented their R&D pipelines by developing their own incubator programs targeted at promising early-stage life sciences companies, academic groups, and individual researchers.

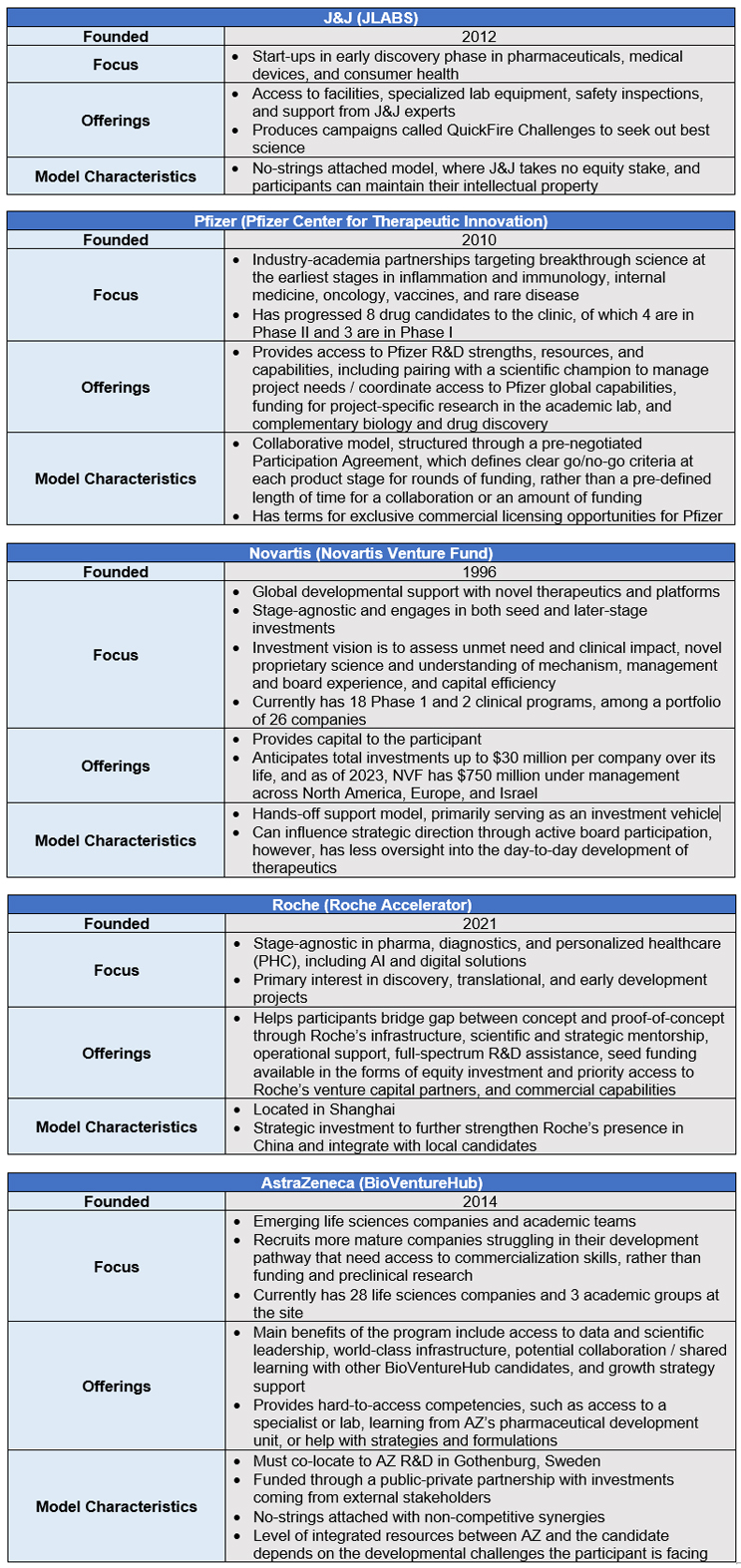

Incubators are programs in which a pharmaceutical company provides selected candidates with resources, such as lab facilities, specialized equipment, direct funding, scientific expertise, connections to the industry, and business guidance. Incubator programs aim to guide and accelerate an incubator participant’s research efforts toward a more robust pathway for achieving clinical development and commercialization. Incubator hosts select promising candidates based on criteria such as a product or scientific platform’s chances of scientific success, commercial potential, and alignment with the host’s internal capabilities. Large industry players such as Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Roche have developed incubator programs over recent years, and in some cases, pharmaceutical companies may incorporate their incubator programs as a venture capital arm (e.g., Novartis).

The growing presence of pharmaceutical incubators can be attributed to the strategic benefits realized by both incubator hosts and participants:

- Benefits to the Host Pharmaceutical Company: To gain access to the latest advances in science and foster portfolio diversification, pharmaceutical companies often look externally to broaden their R&D pipelines. While traditional external innovation pathways, such as M&A, are likely to remain as primary growth strategies, incubators are becoming increasingly attractive, as they offer pharmaceutical companies lower-risk, hands-on opportunities to incorporate early-stage innovation and personnel into their R&D pipeline. In addition, incubator programs are often avenues to explore the potential of early-stage, preclinical assets, although incubator programs can be stage agnostic as well.

- Benefits to the Participant: Early-stage life sciences companies (e.g., startups) may have the scientific knowledge to develop a successful product but many lack the necessary resources and business expertise to move a product into clinical trials and commercial launch. Incubator programs provide participants with the resources and acumen to advance their ideas further and the commercial experience to guide their go-to-market planning.

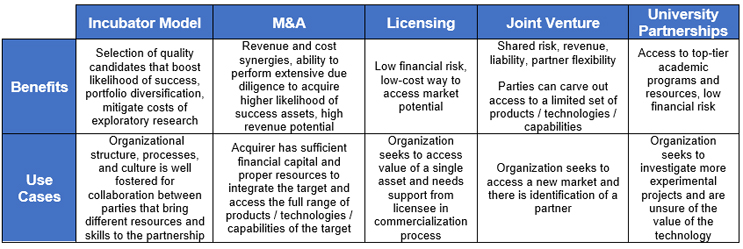

Compared to other traditional business development strategies (Exhibit I), incubator programs are lower risk and partnership-based. A host will realize the greatest benefits when its corporate structure is optimally organized to tap into the value of collaboration with promising candidates.

Exhibit I: Benefits and Use Cases of Different Business Development Strategies

Source: CRA Internal Analysis

Varying Structures Of Incubator Programs

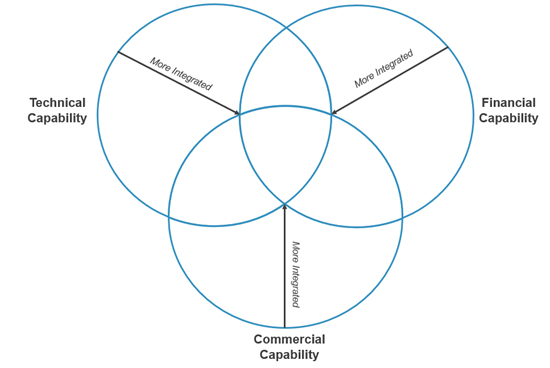

Incubators are structured in ways to help pharmaceutical companies achieve different strategic and operational goals. They can provide a range of capabilities to incubator participants, including technical, financial, and commercial support. Incubators also can vary in the level of long-term organizational involvement with incubator participants. As incubators become more integrated, participants are more likely to tap into multiple capabilities.

CRA conducted an analysis of several pharmaceutical incubators and developed a framework to characterize different incubator designs and the goals of each. The analysis explores the type of support provided and level of integration to gauge the host’s commitment. The framework outlines how each incubator structure offers specific benefits to the host pharmaceutical company. Definitions of the framework components are listed below:

Exhibit II: CRA Incubator Design Framework

Source: CRA Internal Analysis

- Host Capability – Focuses on the types of resources that an incubator program provides to its candidates:

- Technical: Collaboration providing participants with access to scientific expertise, lab facilities, specialized technology, and organizational / research expertise. Incubators that primarily focus on offering technical capabilities tend to leverage clinical knowledge from both entities in forming longer-term thought partnerships to boost likelihood of success.

- Financial: Collaboration in which the host primarily provides the participant with funding to further carry out R&D. Incubators that primarily focus on offering this capability typically are looking for a financial benefit – i.e., return on investment and portfolio diversification.

- Commercial: Collaboration in which the host provides commercial expertise to bring potential pipeline products to market. This level of involvement may occur later in the product development journey and requires a higher degree of organizational integration.

- Level of Integration – Focuses on the level of involvement between the host and candidate, specifically key commitments the incubator participant must make to the host:

- Independent Collaboration: A model where there is no obligation for an equity stake or commercial licensing. Hosts with this model seek to receive an early perspective into viability of early-stage products, in addition to benefitting from shared learning or expertise exchanged between the entities into targeting certain disease areas.

- Organizational Integration: Arrangement in which the host is heavily involved in the incubator participant’s development approach and views the program as a partnership between the two entities. The host is more likely to influence the direction of the incubator participant’s development approach. With this model, hosts may select a small set of candidates with hopes that close involvement may accelerate go-to-market timelines.

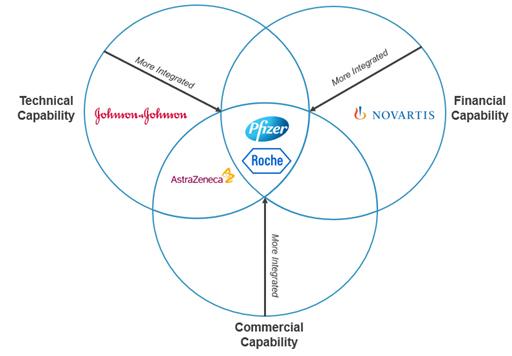

Case Studies for Incubator Program Design

Exhibit III: CRA Case Study Placement on Incubator Design Framework

Source: CRA Internal Analysis

Critical Success Factors for Incubator Programs

Success of incubator programs depends on key factors that position the host organization to take appropriate advantage of the benefits that these programs could offer. Three success drivers include:

- Balance

- Host companies find a balance between quantity versus quality in the selection of candidates. Hosts with sufficient resources to provide mentorship to each candidate raise the likelihood of success for both host and participant. It is important to select a number of candidates to allow appropriate access to and deployment of resources across the incubator program, yet still benefit from a diversification of opportunity. Incubator programs which strategically balance resource commitments as well as number and variety of opportunities are more likely to succeed. To progress in these efforts, companies should develop clear criteria for candidate selection and resource budgeting (both financial and expertise-related).

- Alignment

- There is harmony between the host’s strengths and candidate profile, in addition to alignment with the host’s business development strategy. A candidate is most likely to succeed when there is strategic alignment and complementarity of strengths between the host and the participant. Overall impact increases when the incubator aligns with the rest of the host’s scientific capabilities (e.g., similar therapeutic areas of interest), meaning that company resources are effectively leveraged toward a common goal. Host companies must develop internal alignment and clear corporate goals, as well as an understanding of strengths to be leveraged and gaps to be filled by the incubator program.

- Timing

- Host companies establish realistic time horizons and set expectations accordingly. Due to the significant costs (~$2.6 billion) and time (~10 years) required to develop a new pharmaceutical product, a candidate needs support, at least until proof-of-concept. Pharmaceutical companies which can balance this burden with competing financial challenges are more likely to succeed with their incubators. Hosts should develop performance benchmarks and key performance indicators (KPIs) to assess which candidates deserve more funding and time to succeed.

Future Outlook

CRA expects the pharmaceutical incubator growth trend to continue, given the mutual benefit that both hosts and candidates receive from incubator programs. Incubator programs are less risky and more flexible vehicles to build out an R&D pipeline, compared to more traditional paths. In addition, incubators are aligned with the overall trend toward agility – in resource deployment, talent acquisition and retention, stakeholder engagement, etc. – within the life sciences ecosystem.

Industry leaders can learn from existing incubator programs to inform the design of their own offerings that support the needs of their technology platforms, R&D pipelines, and long-term strategic goals. Organizations aiming to design and improve their incubator programs should align their incubator’s focus areas with their organization’s R&D needs that cannot be met as effectively through other innovation strategies. Organizational goals should be carefully considered when designing an incubator program. If the host is looking to formally build out its R&D pipeline, it could pursue a more organizationally integrated model involving multiple capabilities between technical, financial, and commercial support. If the host is looking to inform the development of its R&D pipeline less formally, it may seek to consider a single capability incubator design focusing on financial or technical support with a greater degree of organizational independence.

About the Authors:

Lev Gerlovin is a vice president wit the global Life Sciences Practice at CRA and has more than 15 years of experience in life sciences strategy consulting, focus on commercial and market access strategies.

Jared Levine is an associate with the global Life Sciences Practice at CRA with experience in strategy consulting, focused on commercial and market access strategies.

Suneil Mendiratta is an associate with the global Life Sciences Practice at CRA with experience in strategy consulting, focused on commercial and market access strategies.

The views expressed herein are the authors’ and not those of Charles River Associates (CRA) or any of the organizations with which the authors are affiliated.