Getting An Accurate Count Of Counterfeit Drugs

By Camille Mojica Rey, Contributing Writer

Follow Me On Twitter

This is the first article in a four-part Life Science Leader series examining the current state of the counterfeit medicines problem. Upcoming stories will examine the issue from the perspective of industry giant Pfizer, look at what is being done by one international coalition to fight the crime, identify efforts to educate patients, and profile a company working to put unique identifiers on individual pills.

Experts in pharmaceutical crime describe it as a global game of cat-and-mouse that can be deadly for patients, costly for pharmaceutical companies, and challenging for government agencies responsible for health and safety. What they are referring to is counterfeit drugs. The Center for Medicine in the Public Interest, a New York-based research group partially funded by the pharmaceutical industry, estimates that the sale of fake medicines will generate $95 billion this year, an increase of 26 percent since 2010.

It is a problem that continues to grow in scale and complexity, says Thomas Kubic, CEO of the Pharmaceutical Security Institute (PSI), a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization. “We have seen medicines marked as donations to African nations end up in a Caribbean-based online distribution system targeting U.S. customers,” Kubic says.

According to Kubic, the biggest problem facing the industry 15 years ago was that pharmaceutical crimes were not being pursued by law enforcement, largely because the magnitude of the problem was unknown. In response, industry leaders in 2002 created PSI, taking it upon themselves to provide law enforcement with a more accurate picture of the global pharmaceutical crime problem. Prior to the institute’s creation, the WHO was reporting an average of 50 law-enforcement events involving pharmaceutical crimes per year. Last year, PSI reported 3,002 incidences.

“These numbers more accurately reflect the scope of the problem,” Kubic says. “Nobody knows for sure how big a problem it is; we only see indicators. But, for years, we lacked those basic numbers.”

According to Kubic, the current data indicates that the industry is making progress. “We have seen a significant increase in seizure activity, as well as the dollar value of goods that have been subject to enforcement activity,” Kubic explains. In 2011, PSI reported 18 tons of illegal drugs seized by customs agents, police, and drug regulators. By 2015, that number grew to 423.9 tons.

TRACKING CRIME

One can assume that PSI has been so effective because the organization employs the likes of Kubic. He was once head of operations at the FBI’s Salt Lake City office and, later, was in charge of what was known as the FBI’s white-collar crime division.

Kubic and his similarly trained colleagues at PSI developed their Counterfeit Incidence System (CIS) in 2002. By using case report details, such as the amount of counterfeit product seized, the system tracks the number of law enforcement cases involving pharmaceutical crimes.

“One of the first things we wanted to do was identify the extent of the problem,” Kubic says. That led to the creation of CIS.

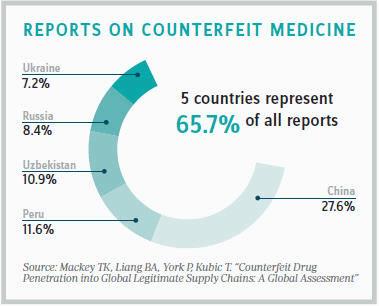

Using this system, Kubic and his colleagues analyze data for trends that can pinpoint the source of batches of counterfeit medicines so that they can then alert the appropriate authorities.

Kubic and his colleagues can also help law enforcement officials decide where to focus their efforts. Recently, they began defining as “commercial” those incidents of pharmaceutical crime involving more than 1,000 dosage units. Anything less than that is now classified as “noncommercial.” Last year, one-third of the seizures was commercial in size, while 56 percent were noncommercial. (The rest were of unknown size.)

In addition to surveillance and trend analysis, PSI offers law-enforcement training to customs agents and other authorities. These trainings have increased the number of seizures made by those who have completed training, Kubic says.

COOPERATION AMONG COMPETITORS

PSI began in 1992 as an informal meeting of 14 security directors from drug companies. These directors realized that the counterfeit drug problem was not one that any single drug maker could tackle on its own. Cooperation was required.

The group originally focused on conducting its own investigations and then sharing its results with local agencies. Many of these agencies were unaware that pharmaceutical crime was taking place in their own jurisdictions.

Working individual cases themselves, however, was not having the global impact needed to truly curtail pharmaceutical crime. It became clear that hard data was needed to get international law enforcement to devote the resources to apprehend the perpetrators of pharmaceutical crime.

PSI defines counterfeit medicines as branded or generic products deliberately and fraudulently produced. Counterfeit medicines are also authentic products that have been mislabeled to obscure true identity or source.

Data that goes into the CIS include incidents of counterfeiting, theft, and illegal diversion of pharmaceutical products worldwide. CIS incidents come from a variety of sources, including open media reports, PSI member company submissions, and public-private sector partnerships.

GETTING GLOBAL BUY-IN

Today, PSI is made up of 33 pharmaceutical manufacturers from around the world and has additional offices in London and Hong Kong. The organization has been able to raise awareness about the magnitude of the global pharmaceutical problem, and that, in turn, has led to increased global cooperation among law enforcement organizations. For example, Interpol began its Operation Giboia in 2013. In 2015, the operation involved 2,100 police, customs agents, and health officials who conducted raids in seven countries. Authorities raided markets, shops, warehouses, pharmacies, clinics, and ports in more than 50 cities and seized more than 150 tons of counterfeit and illicit medicines worth an estimated $3.5 million.

In addition to data collection, Kubic and his colleagues continue to conduct their own investigations, sharing information with law enforcement officials about criminal activities in their jurisdictions. Getting the authorities to act on that information, however, can sometimes be difficult. Pharmaceutical crimes are competing for resources with more urgent cases involving violent crimes, he says.

![]() "We have seen a significant increase in seizure activity, as well as the dollar value of goods that have been subject to enforcement activity."

"We have seen a significant increase in seizure activity, as well as the dollar value of goods that have been subject to enforcement activity."

Thomas Kubic

CEO, Pharmaceutical Security Institute

PREVENTION MAKES SENSE

The fight against pharmaceutical criminals is a multifaceted one that requires not only law enforcement, but also prevention. Kubic says efforts by manufacturers to track-and-trace goods have been good and are getting better. “The big discussion among manufacturers is about the unique identifier,” he says. “I think it is a good idea.”

Criminals are now going directly to doctors to try to sell their goods. The ability to do that would be greatly reduced if every package has a unique identifier and every doctor, pharmacist, or wholesaler has access to a scanner that can verify that unique number in a database. No one can predict whether such a system will be adopted on a global scale. But, if doctors choose not to utilize this system to verify authenticity, they are knowingly putting their patients in jeopardy.

“If you’re a doctor and you’re buying medicines that are unapproved for sale for whatever reason, that’s a federal crime. You don’t want to lose your license,” Kubic says.

In the United States, visits to doctors’ offices by the FDA’s Office of Criminal Investigation (OCI) have come under scrutiny — even by some of its own agents. In a September, Reuters reported that some FDA agents complained they had become the “Botox Police.” They charged that few of the doctors who purchased authentic versions of the antiwrinkle drug that were labeled for use in other countries were ever prosecuted. One reason that happens, Kubic says, is that federal prosecutors from different regions have different thresholds for deciding when they will file charges. If the threshold is $25,000, for example, a person could technically escape charges if they were responsible for a theft totaling $24,999.

Despite OCI’s record on federal charges filed, it is not a waste of time for FDA agents to visit doctors’ offices. “If they don’t know they are buying illegal medicines, then they are going to get some good advice,” Kubic says. “If they do know, they need to be held accountable.”

Other experts interviewed say it is precisely because the United States has such tight regulations that we don’t have problems like the ones seen in Asia and Africa, which have hundreds of thousands of deaths due to widely circulated fake malaria drugs.

Here in the U.S., the real problem is people buying counterfeit medications off of the Internet. One illegal organization often operates thousands of websites. Drug companies and others fighting pharmaceutical crime are using complex algorithms to locate these distributors and put them out of business.

Another way to track down those selling counterfeit drugs on the Internet is to screen patients who complain to the manufacturer of adverse events. “Those folks in the customer care centers need to be asking consumers where these people got their medications,” Kubic says. PSI is working on a larger detection strategy that includes training for call center staff.

Kubic also says emerging methods to use plant DNA in inks used directly on individual pills offers promise. “That would go beyond putting numbers on boxes and would tell us what’s inside of the box.”

"We have seen a significant increase in seizure activity, as well as the dollar value of goods that have been subject to enforcement activity."

"We have seen a significant increase in seizure activity, as well as the dollar value of goods that have been subject to enforcement activity."