Healthcare Delivery Consolidation Spells Higher Costs And Less Competition

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

The consolidation of healthcare delivery over the past several years has been substantial and is accelerating with the implementation of Obamacare. But what are the implications for patients and those paying the bills — employers and taxpayers?

The consolidation of healthcare delivery over the past several years has been substantial and is accelerating with the implementation of Obamacare. But what are the implications for patients and those paying the bills — employers and taxpayers?

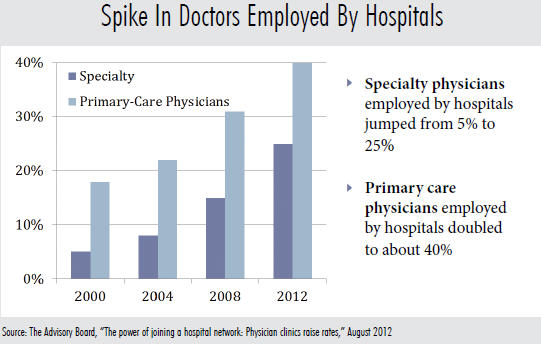

A survey by the Medical Group Management Association shows a nearly 75 percent increase in the number of active physicians employed by hospitals since 2000, while 74 percent of hospital leaders planning to increase physician employment within the next 12 to 36 months.

Medicare payment cuts on certain procedures in physician offices have resulted in increased hospital acquisition of particular specialties, notably cardiology and oncology. For example, the percentage of cardiology practices employed by hospitals more than tripled from 2007 to 2012, rising from 11 percent to almost 35 percent in that time.next 12 to 36 months.

Similarly, hospitals are acquiring ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), which provide outpatient surgical care, at a rapid pace. Analysis by the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association found half of the 150 ASCs that closed since 2009 were purchased by a hospital and are now operating under hospital license and billing at the substantially higher Medicare payment rate of hospital outpatient departments. Hospitals often retain the center’s physicians, nurses, and even the name on the building (e.g. The Louisville Endoscopy Center), but bill 78 percent more for the identical procedures it delivered before.next 12 to 36 months.

Proponents of this consolidation claim that it has the potential to improve care coordination and better lends itself to bundled payments and capitation, which can contain costs. They argue salaried physicians who are no longer paid by the procedure will be discouraged from ordering unnecessary tests and procedures. The narrative for years in the health policy community has been that physician ownership and independent, uncoordinated physician practices have incentives to overutilize care.

Obamacare fully subscribes to this line of thinking through promotion of so-called “Accountable Care Organizations,” where care would be delivered through consolidated health systems that would be responsible for the continuum of care provided to patients. If treatment costs less than set targets and established quality measures are met, the ACO health care providers would share in the savings.

However, it is worth noting that the proposed ACO regulation would have penalized ACO providers that exceeded the target. But that proposal was quickly scrapped after vocal protests by the hospital industry. As a result, the ACO model provides only an upside if costs come in below targets but absolutely no downside if costs exceed expectations. Heads I win, tails you lose.

The ACO roll-out has expedited hospital acquisitions of physician practices, ASCs, and other free-standing centers, in part because physician practices and other providers are being told they could be frozen out of the market and denied access to patients if they do not join up now as part of a hospital-based ACO.

But does hospital acquisition actually reduce costs? And what are the impacts on patient care?

What Does MedPAC Have To Say?

In an interesting turn of events, the Medicare Payment Advisory Committee (MedPAC), which advises Congress on payment policy, has taken notice of this rapid consolidation and noted that hospitals are being paid substantially more for identical procedures that can be provided in the physician’s office.

In its June 2013 report, MedPAC stated, “If the same service can be safely provided in different settings, a prudent purchaser should not pay more for that service in one setting than another. Payment variations across settings may encourage arrangements among providers that result in care provided in higher-paid settings, thereby increasing total Medicare spending and beneficiary cost sharing.”

MedPAC goes on to recommend reducing hospital payment rates to the physician office level for “Evaluation & Management (E&M)” procedures commonly performed in physician offices, which would save Medicare more than $10 billion over the next 10 years. A similar policy applied to hospital-based cardiac medical imaging, where echocardiograms are as much as 141 percent more expensive in the hospital than in physician offices, could result in more than $1.7 billion in savings per year.

The hospital lobby is aggressively pushing back on these proposals, arguing that hospitals need this revenue to offset their uncompensated care and poor Medicaid payments, notwithstanding they get special payments exclusively available to hospitals and not physician practices (e.g. Medicare and Medicaid disproportionate share and bad debt). Last Congress, the Senate blocked a House-passed proposal to equalize E&M payments for hospitals and physician offices.

While Medicare payments are set by statute and depend heavily on the lobbying prowess of the competing industries and Congress’s interest and ability to enact reforms, perhaps the more fundamental impact of this consolidation is on the commercial market.

Hospitals are merging into megasystems and purchasing physician practices to eliminate competition and secure referrals. In a seminal synthesis report issued in June 2012, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation made three key findings with respect to consolidation:

- Hospital consolidation results in higher prices.

- Hospital competition improves quality of care, whether under administered pricing or private insurance.

- Hospital-physician consolidation has not led either to improved quality or reduced costs. Indeed, studies find that consolidation was primarily for the purpose of enhanced bargaining power with payers.

Similarly, the basic economic principle of competition resulting in lower prices is also evident in Medicare’s Part D prescription drug program. The Congressional Budget Office found lower bids were submitted in the Part D regions with more prescription drug plan sponsors. Between 2007 and 2010, each additional plan sponsor in a region correlated with a 0.5 percent reduction in the average bid for that region.

Unfortunately, the Obama administration would exacerbate this consolidation phenomenon by advancing its proposal to prohibit physician practices from integrating so-called “ancillary services” — advanced medical imaging, radiation, and physical therapy — into their practices. The result is that these services would be provided primarily in hospitals, which are more expensive and less convenient for patients. More importantly, the proposal would undermine the independent physician practice, and many of these physicians would throw their hands in the air and conclude that staying independent of hospitals is economically unfeasible and join many of their colleagues as employees of mega-hospital systems.

The reaction to this proposal of the House physician caucus (i.e. members of Congress who were physicians before they became Congressmen) has been unified and alarmed. The letter signed by 17 members of the caucus states, “We hope you will reject this unwise policy that will legislatively undermine the important counterbalance provided by integrated physician groups that provide ancillary services, which we believe is essential to America’s patients and taxpayers alike.”

If MedPAC, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and knowledgeable physician members of the House of Representatives are waving red flags about the negative implications of this health delivery consolidation, why is the Obama administration aggressively pursuing policies that accelerate this phenomenon?

Answer: Centralization of fewer, powerful entities is easier for big government to regulate and control than thousands of independent, free-thinking physician practices with their own ideas about how best to deliver care to their patients.