If Four-Letter Suffixes Aren't Used In Biosimilar Tracking, What Use Are They?

By Stanton R. Mehr, Content Director, Biosimilars Review & Report

The implementation of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act1 (BPCIA) raised a number of critical issues for manufacturers, payers, and prescribers. These include the big-picture questions of extrapolation of indications, interchangeability, and a radical new approach to evaluating the comparability of these drugs to their reference biologics, as well as approving them.

The Great Naming Debate

Perhaps the most controversial issue around the introduction of biosimilars was how to name these products. The nomenclature question has elicited strong, almost visceral, reactions of stakeholders. Each sector hotly debated the need and potential methods to positively differentiate which biosimilar agent was prescribed to any one patient.

Driven by worries over possible safety issues with use of these new drugs, patient advocates and physicians asked how postmarketing surveillance of biosimilars will be conducted. Reference manufacturers stoked these fears, encouraging questions over whether biosimilar agents were so different that immunogenicity, loss of efficacy, and antibody development were real probabilities. Biosimilars were supposed to be just as effective as their reference products; doesn’t adding some confusing mix of letters to their name somehow label them as inferior?

Even if biosimilars require careful postmarketing monitoring, couldn’t this be accomplished with individual National Drug Codes (NDCs)? This was the argument of most payers, who are increasingly requiring NDCs for medical claims as a condition for reimbursement.

The European Union, which pioneered the biosimilar approval process, did not utilize any special designations. The World Health Organization released its recommendations for biosimilar naming two years prior to the FDA’s final guidance.2 It did in fact require a “biologic qualifier” attached to the international nonproprietary name (INN), consisting of four random consonants in two two-letter blocks separated by a two-digit number. This may have influenced the FDA’s thinking, perhaps even anticipating a move toward global harmonization.

The FDA Stokes Confusion

A hint at what was to come was apparent with the approval of Neupogen’s first competitor, Granix. Its biologic licensing application was filed before the promulgation of the 351(k) pathway; Teva’s product was approved in August 20123 and given a prefix: tbo-filgrastim. According to the FDA, this was also done to “minimize medication errors and to facilitate pharmacovigilance.” The FDA has used such a prefix in another instance, to distinguish ado-trastuzumab emtansine from trastuzumab. The agency indicated that it “may continue such practices on a limited basis, where appropriate, when the agency determines that the designation of a prefix, in addition to a suffix as contemplated by this guidance, is necessary to ensure patient safety.”4

In 2014, before the FDA published its final rule on biosimilar naming, it approved the first U.S. biosimilar,5 assigning it a four-letter suffix (filgrastim-sndz). Clearly, the assignment was related to the name of the manufacturer of Zarxio, Sandoz. At the time, the FDA indicated that this suffix was simply a “placeholder name,”6 which would be adjusted to be in alignment with the final rule. In its final rule, published in January 2017,4 the FDA moved along these lines, mandating the use of a four-letter suffix for all new biosimilars and biologics, as well as assignment of a similar suffix for all available biologics. Yet, the agency also specified that the suffix must be a random set of letters that were nonsensical. More than four years later, the FDA has not announced whether it will redesignate Zarxio’s suffix to conform with the rule.

Adding even more confusion, the FDA posed a new idea: it would give biosimilar manufacturers the opportunity to provide up to 10 potential nonsensical suffixes at the time of BLA submission, to be considered by reviewers. It is not known whether the FDA has chosen exclusively from this list for the naming of all (or any) biosimilars.

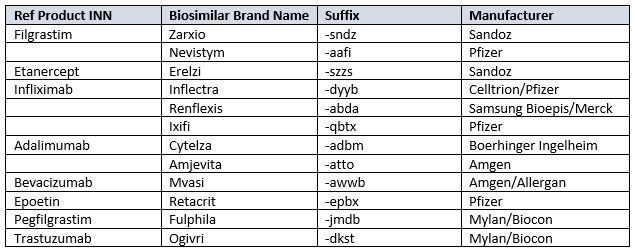

Table 1: Approved Biosimilars And Their Nomenclatures7

Consequences Of Applying Suffixes To Existing Biologics

Fueling the controversy over the four-letter suffixes is an extremely pragmatic issue. The application of this rule to currently marketed reference biologics can play havoc with information technology, claims systems, and electronic health records. The impact on resources for adapting claims payment, electronic medical record systems, and other administrative databases could be considerable, both in cost and time, for private and public payers.

If these suffixes were added to currently marketed biologics, up to 40 hours of work might be needed per product to change the system. In 2017, Erin Fox, Pharm.D., FASHP, director of the University of Utah Health Care’s Drug Information Service, asserted that their calculation included addressing the implications of such a move on drug labeling, scanning software, and pharmacy automation.7 Further, the addition of a four-letter suffix would have negative effects on a pharmacy’s ability to use up existing stock; the pharmacy will likely not be reimbursed for existing inventory that has not been relabeled.

There are no indications today that the FDA will move forward with this particular effort, despite its inclusion in the final guidelines. This could indicate a reticence on the government’s part, and even perhaps room for reconsideration of the concept. This may be of further consequence, as described below.

Suffixes’ Lack Of Memorability Undercuts Intended Benefits

In discussions with individual pharmacists, something is becoming clear. The random suffixes have achieved an unintended aim — although the biosimilar nonproprietary names do not stand out, managed care pharmacists are also mostly unable to associate the suffix with a biosimilar (except for Zarxio). This may change with far greater utilization and uptake, but with additional biosimilars in the queue for approval, this situation is likely to worsen.

James G. Stevenson, Pharm.D., professor, Department of Clinical Pharmacy at the University of Michigan’s College of Pharmacy, agreed with this view. In remarks made at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy’s Nexus 2018 meeting last week, he said, “The problem, in my view, is that the suffix is devoid of meaning, making it unmemorable.”8 He believes the practice makes it difficult to communicate with prescribers. “Are you going to remember which biosimilar is which, when we have a bunch of them for the same drug?” he asked. Instead, Stevenson uses the brand name to identify a specific biosimilar.

As stated at the outset, the reason for the nomenclature choice was to assist accurately tracking of biosimilar use for postmarketing surveillance. However, this may be the major problem that could have the FDA rethinking its strategy.

Like Stevenson, prescribers may be avoiding use of the suffix. At a September 2018 meeting of the Association of Affordable Medicine (AAM), Hillel Cohen, Ph.D., of Sandoz, presented data demonstrating that of 69 adverse drug reports (ADRs) related to Zarxio received by the manufacturer, 65 were filed using the brand name only. None of the other four ADRs reports included the four-letter suffix of the product.9

In October 2018, the Pink Sheet reported on a much broader analysis.10 Of the over 2,500 adverse event reports (ADRs) associated with biosimilar use in the U.S., only a tiny fraction have been filed using the four-letter suffix. This analysis utilized the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Through the end of the second quarter of 2018, 11 ADRs (0.4 percent) were filed using the biosimilar’s nonproprietary name and suffix. The remaining 99.6 percent identified the biosimilar agent by brand name only.

Granix (tbo-filgrastim) was not approved under the 351(k) pathway and was not included in the analysis. With a prefix rather than a suffix, its inclusion would have been problematic. Still, 94 percent of its 139 ADRs were reported by brand name only.10

In comparison, Amgen’s reference filgrastim agent (Neupogen) has been the subject of 10,744 ADRs since 1991, and more than two-thirds (69 percent) cited the brand name.10

Is the brand name used in adverse event reporting because people are confused by or cannot remember the correct suffix? This is also a possibility.

Members of the EU do not utilize any suffixes and seemingly have little problem attributing an ADR to a particular brand. Cohen pointed out at the AAM meeting in September that using the brand name only did not result in any less ability to identify which biosimilar product was used in a specific instance.9

In the United States, the Biosimilars and Biologics Collective Intelligence Consortium (BBCIC; www.bbcic.org) was created to address concerns with biosimilar safety and efficacy, including loss of potency (lot to lot variations). This organization is evaluating potential safety signals through administrative databases (e.g., claims databases). BBCIC Program Director Cate Lockhart, Pharm.D., Ph.D., recently stated that although the biosimilar nomenclature has been adopted by the FDA, if the suffix is not being entered into the claims systems, BBCIC cannot track drugs using it.11 “For tracking purposes, there could be benefit in using the four-letter suffix,” said Lockhart, “but we can’t track it effectively if people are not using it for coding. And some of the coding systems being used today are not really designed to enter the suffix, so prescribers and administrative folks actually can’t code it in.”

Not that this will make comparative-effectiveness research or obtaining real-world evidence any less possible. It is just that, at this moment, trying to track biosimilars by their nonproprietary name and suffix yields almost no results, she said. To commence the work of BBCIC, it will have to monitor the use of these products via the brand name or NDC.

Lack Of FDA Guidance Could Cost Manufacturers

The FDA’s final naming guidance did not specify how it will handle the assignment of suffixes for interchangeable products. To this date, the agency has not yet decided on how it will handle interchangeable agents in terms of the four-digit suffix. Originally, the possible avenues included having a suffix that is identical to the reference biologic, including a standard suffix that characterizes a biosimilar in any category (which then could become confusing if two biosimilars in the same category are designated interchangeable), and assigning a standard random four-letter suffix without regard to interchangeable status.

Despite the fact that the draft guidance on determining the interchangeability of biosimilars was first published in January 2017,12 the final guidance from the FDA has not been published to date. Perhaps as a result, no pharmaceutical manufacturer has yet sought that designation.

Yet, Boehringer Ingelheim is seeking interchangeable status for Cyltezo; switching studies13 have commenced in anticipation of finalized guidelines for attaining the interchangeability designation. Biosimilar drug makers that are interested in obtaining interchangeable status might be best served by first gaining approval for their agent as a standard biosimilar. The switching studies necessary can be complicated, cost a great deal of money, and take several years to complete. In Boehringer’s case, Cyltezo is already approved and assigned a four-letter suffix — adbm. Although it may not be marketed until its patent litigation is settled or 2023 (whichever comes first), a change in the suffix may cause practical problems.

A Way Ahead

Although the FDA does not have the authority to compel doctors to use the unique suffixes to identify which biosimilar has been prescribed, the healthcare system seems to be voting by its actions. The only purpose of suffixes is to identify specific drugs for postmarketing and tracking, and they are not being used (nearly at all) for claims or adverse event reporting. And yet, ADRs are being accurately correlated with their products, at least early on in biosimilar utilization.

The agency may want to take the opportunity to reevaluate this situation. Particularly with only five biosimilars on the market, it may not be too late to simplify biosimilar nomenclature and diffuse one issue that may make it more difficult to prescribe biosimilars. That approach may align more closely with current initiatives that encourage biosimilar uptake.

References:

- The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA), of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 111-148, 124 Stat. 118, 804 (111th Congress) (2010). www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf.

- Biological Qualifier An INN Proposal Programme on International Nonproprietary Names (INN). World Health Organization. 2015. https://www.who.int/medicines/services/inn/WHO_INN_BQ_proposal_2015.pdf?ua=1.

- BLA Approval of tbo-filgrastim. Food and Drug Administration August 29, 2012. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2012/125294Orig1s000ltr.pdf.

- Nonproprietary naming of biologic drugs: Guidance for industry. Food and Drug Administration January 2017. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm459987.pdf.

- BLA Approval of filgrastim-sndz. Food and Drug Administration March 6, 2015. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2015/125553Orig1s000ltr.pdf.

- Bonner L. FDA approves first biosimilar drug. American Pharmacists Association April 1, 2015 https://www.pharmacist.com/article/fda-approves-first-biosimilar-drug.

- Biosimilars Reviews & Reports. https://biosimilarsrr.com/us-biosimilar-filings/.

- Barlas S. FDA pleases no one with final guidance on naming of biologicals and biosimilars. P&T 2017;42:222,241.

- Stevenson JG. Biosimilars in practice: a guide for managed care professionals. Presented at the 2018 Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Nexus meeting. October 23, 2018.

- Mehr SR. More from GRx+Biosims on four-letter suffixes and biosimilar interchangeability. Biosimilars Review & Report September 20, 2018. https://biosimilarsrr.com/2018/09/20/more-from-grxbiosims-on-interchangeability/.

- Gingery D. Biosimilars suffixes appear superfluous to adverse event reporting. Pink Sheet October 10, 2018. 80(41):11-13.

- Mehr SR. An update from BBCIC: A conversation with Cate Lockhart, Program Director—Part 2. Biosimilars Reviews & Report October 12, 2018. https://biosimilarsrr.com/2018/10/12/an-update-from-bbcic-a-conversation-with-cate-lockhart-program-director-part-1-2/.

- Considerations in Demonstrating Interchangeability With a Reference Product: Guidance for Industry—draft guidance. Food and Drug Administration January 2017. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM537135.pdf.

- The VOLTAIRE-X trial looks at the effect of switching between Humira® and BI 695501 in patients with plaque psoriasis. U.S. National Library of Medicine Clinicaltrials.gov October 3, 2018. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03210259?term=BI695501&rank=9.

About The Author:

About The Author:

Stanton Mehr is content director of Biosimilars Review & Report (www.biosimilarsrr.com) and president of SM Health Communications (www.smhealthcom.com). He consults on payer issues, health policy, and the biosimilar arena. You can contact him at stan.mehr@smhealthcom.com.