Is This The Pearl Harbor Moment For The U.S. Pharma Supply Chain?

By Thomas Giannone

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to evolve at a rapid pace, it has revealed numerous fields for inquiry, debate and consideration. Among them is the U.S.’s preparedness to react to the potential risks of a global supply chain. Without entertaining the blame game, it is reasonable to surmise that we were not adequately prepared for this COVID-19 crisis.

In particular, our dependence on a global healthcare system – evidenced by the recent lack of PPE and, to a lesser degree, disruption to the supply chain of essential pharmaceutical drugs – has revealed evident gaps in our preparedness. History has shown that gaps, especially in a global context, can lead to disastrous consequences, with Pearl Harbor being the most tragic.

Gaps also exist today in our country’s collective knowledge required to determine the severity of the current pandemic’s risk to our supply chain for drugs. Undoubtedly, these gaps will remain leaving questions that need to be answered and will, hopefully, serve as a roadmap for legislators and advocates of the industry.

THE COMPLEXITY OF THE PHARMACEUTICAL SUPPLY CHAIN

The U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain is complex for many reasons, including the variety of components needed in the final form of a drug. These components resulting in the final dosage form (FDF) include APIs, the active pharmaceutical ingredients that establish a drug’s efficacy; KSMs, the key starting materials that are the raw materials and intermediates of a drug substance; and excipients, which are formulated alongside the API and serve many purposes including long-term stabilization and bulking up the API.

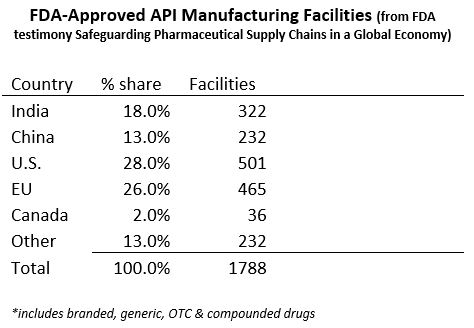

Since an API produces the intended effect of the drug, its production is key to the safety of the supply chain. To manufacture APIs for export into the U.S., facilities must be pre-approved by the FDA. There are 1,788 FDA approved manufacturing facilities across the globe, distributed as follows:

China and India have the potential to manufacture the greatest quantity of APIs, but the supply chains for pharmaceuticals with both countries are particularly complex and interdependent. China is the world’s largest supplier of APIs and as of 2018 ranks second among countries that export drugs and biologics to the U.S. APIs manufactured by China also come to the U.S. as part of FDFs manufactured in other countries such as India.

It has been concluded by industry experts that the percentage of APIs produced by China for the U.S. is likely underrepresented by the expert numbers, as China is also a major supplier of APIs for other countries. This lack of a reliable API registry makes it difficult to estimate the true market share of Chinese-made APIs. India is ranked as the world’s main supplier of generic drugs, supplying up to 50% of all U.S. generics - however, India also imports nearly 70% of its APIs from China.

Until more data is available on China API production, it is helpful to evaluate the importation of APIs contained in branded vs. generic drugs. Dr. Gerard Anderson, a professor of health policy and international health at Johns Hopkins University has been quoted as saying that the U.S. is generally at a low risk of API production when it comes to branded drugs. Pfizer spokeswoman Kimberly Becker says less than 2% of their APIs and key materials are sourced from China and David A. Ricks, the CEO of Eli Lilly, has publicly stated that all of Lilly’s APIs are manufactured in either Europe or the U.S. However, we remain dependent on international sources of generic drugs especially because generic drugs are based on price competition.

It can be concluded that the U.S. dependency on APIs can be traced through the supply chain of generic pharmaceuticals. Due to the plethora of generic drugs on the market and the focus of the U.S. healthcare system to encourage the use of generic drugs for cost control reasons, it is helpful to determine which drugs are essential to the health of the U.S. population.

A list of “essential” vs. “non-essential” drugs is published by the World Health Organization (WHO), updated biannually, and is known as the Essential Medicines List (EML). Essential drugs are those that meet the most important needs in a health system. Currently, the WHO classifies 462 drugs as “essential” on the EML and according to the World Intellectual Property Organization, 95% of the drugs on the WHO’s EML are off-patent (generics) and the roughly five percent remaining are largely antivirals. Three WHO Essential Drugs are only manufactured in China.

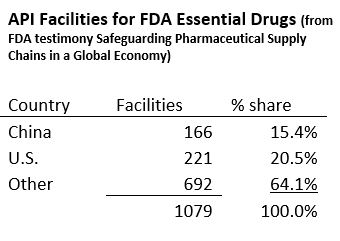

Therefore, the focus on the origin of generic drugs and its components, specifically APIs, is critical to the evaluation of the risk of the U.S. supply chain. The FDA matched 370 drugs on the EML with products that are marketed in the U.S. including drugs for Medical Countermeasures (MCM) to counter biological, chemical, nuclear or radiation threats and influenza. The FDA-regulated Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) maintains a Site Catalog of all manufacturing facilities making drugs for the U.S. market including the facilities for these 370 drugs.

Concerning the critical MCM drugs for which many are contained in the U.S.’s Strategic National Stockpile, China has 21% of the API sites for meeting biological threats and 7% for chemical threats.

Unfortunately, drawing conclusions from the existing data has limitations. Although FDA-approved, these facilities may actually not be producing APIs. Manufacturers are not required to report if they are producing APIs and at what quantity. Drugs from these APIs may be exported to both the U.S. and other countries, while some APIs distributed in the U.S. are formulated in FDFs that are then exported. Some FDF applications list various API suppliers but with no required visibility on which supplier was used.

ASSESSING THE RISK

The potential risks for the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain are ultimately defined by shortages of drugs and/or critical drug components. The vital links in any drug supply chain include APIs, KSMs and excipients with APIs being the most critical. However, we all know that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

As outlined above, sources of overseas manufacturing include countries whose national interests conflict to varying degrees with the interests of the U.S. The COVID-19 situation has certainly raised the issue of our dependency on API production in China as addressed by Senator Tom Cotton in which he stated, “a Chinese Communist Party propaganda outlet insinuated that Beijing could cut off supplies of life-saving medicine to the United States at any time.”

Meanwhile, India restricted the export of 26 APIs and FDFs, saving them for domestic use and has implemented a 21-day shutdown of nearly all services starting March 25, which would have an inevitable impact upon its ability to supply drugs. However, India agreed to lift the export ban on hydroxychloroquine at President Trump’s urging.

According to FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, despite the current exposure, the FDA has not seen a shortage of APIs sourced from China as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, but the FDA is “closely monitoring the situation.” He added, “We don’t have any evidence that there’s a drug in short supply because of anyone blocking APIs coming to us from China.”

However, we don’t know how much of China’s API output reaches the U.S. market through other countries. To further assess the risks associated with the security of the nation’s drug supply, we need to know more about our dependence on foreign sources of API. We need to ask questions such as what volume of APIs is being produced at each facility in India/China for the U.S. market and what percentage of U.S. drug consumption this represents as well as how much is distributed in the U.S. market vs. exported to other countries.

We also need to understand the resilience of the U.S. domestic manufacturing base to meet demand if supply is cut off.

For example, how much unused capacity exists in U.S. facilities? What percentage of total needs does this represent if less than 100%? How long would it take to increase capacity and at what cost? In addition, it’s important that we get a better handle on the reliability of the facilities that make quality products for U.S. market.

The bottom line is that there’s no way of knowing if U.S.-based API manufacturing facilities could fulfill the requirements if a foreign country stopped producing our required APIs. In addition, the feasibility for the U.S. to construct new facilities is limited under current manufacturing practices.

THE LONG-TERM SOLUTION - TECHNOLOGY VERSUS LOWER COST COMPETITION

For the United States to compete globally in the manufacturing of APIs, especially those contained in generics, we must find a way to leverage technology to reduce the labor cost differential. The FDA’s 2011 report “Pathway to Global Product Safety and Quality,” noted that both China and India enjoy a labor cost advantage and that API manufacturing in India can reduce costs for U.S. and European companies by an estimated 30 percent to 40 percent.” China has the following advantages including:

- Most traditional drug production processes require a large factory site, which often have existing environmental liabilities.

- China has a low-cost labor force. If a typical western API company has an average wage index of 100, this index is as low as 8 for a Chinese company and 10 for an Indian company.

- China enjoys lower electricity, coal, and water costs.

- Chinese firms are also embedded in a network of raw materials and intermediary suppliers and, therefore, have lower shipping and transaction costs for raw materials.

- Chinese pharmaceutical manufacturers face fewer environmental regulations regarding buying, handling, and disposing of toxic chemicals, leading to lower direct costs for these firms.

According to the FDA in an October 2019 testimony “Safeguarding Pharmaceutical Supply Chains in a Global Economy” using traditional pharmaceutical manufacturing technology, a U.S.-based company could never offset the labor and other cost advantages that China enjoys simply by achieving higher productivity. However, the FDA believes that advanced manufacturing technologies could enable U.S.-based pharmaceutical manufacturing to regain its competitiveness with China and other foreign countries, and potentially ensure a stable supply of drugs critical to the health of U.S. patients. Advanced manufacturing technology, which the FDA supports through its Emerging Technology Program (ETP), has a smaller facility footprint, lower environmental impact, and more efficient use of human resources than traditional technology…”

THE U.S. GOVERNMENT’S RESPONSE

There have been several legislative actions proposed to address the risks associated with the drug supply chain. Legislation by Senators Menendez and Blackburn was introduced in the Senate and is known as Securing America’s Medicine Cabinet (SAM-C). According to Senator Blackburn, “Congress and federal agencies can start now by reviewing regulations to ensure there are no barriers to rapid adoption of new technologies, creating incentives for workforce growth and training, and allowing the private sector to use updated, cost-effective technologies and processes that would enable U.S.-based companies to regain competitiveness in the API market.”

On March 19, Senator Tom Cotton and Congressman Mike Gallagher, introduced the “Protecting our Pharmaceutical Supply Chain from China Act” which proposes to track active pharmaceutical ingredients through an FDA registry; prohibit pharmaceutical purchases from China or products with active pharmaceutical ingredients created in China; create transparency in the supply chain by instituting a country of origin label of all imported drugs; and provide economic incentives for manufacturing drugs and medical equipment in the United States.

Senator Marco Rubio is also planning to introduce legislation that will require drug makers to provide FDA with the volume of APIs derived from each manufacturing source in the prior year. It would be included in the drug maker’s annual post market report already required by FDA. In addition, the legislation will restore Buy America Act preferences for pharmaceuticals and combat supply chain risk and U.S. dependence on China for APIs.

Senior Presidential Advisor Peter Navarro is also preparing an Executive Order that would reduce American dependency on foreign suppliers for medicine by moving production of essential medicines to the U.S.

A FINAL PERSPECTIVE TO CONSIDER

There are many questions to be answered and gaps in the data to be researched before any meaningful and effective strategic plan can be developed and implemented. We know the supply chain is global, complex and heavily reliant on overseas production from both reliable and sometimes not so reliable foreign countries. The risk is real as confirmed by Sen. Blackburn notes that, “Although we cannot yet quantify the U.S.’s dependence on pharmaceutical ingredients made in China, we do know that the more Chinese products flow into the U.S., the more potential there is for trouble.”

There is an urgent need for data to assess the risk before Congress will act on a potential future crisis, especially after a $2 trillion federal stimulus package to a very real current crisis: COVID-19.

The commercial imperative of near-shoring is a trend in many other sectors of the economy, as was recently highlighted in the Avison Young 2020 Forecast report. If the U.S. indeed decides that the most effective way to mitigate the risks to our drug supply chain in the long-term is to “on-shore” the production of APIs (and possibly finished drugs, KSMs and excipients), there must be a coordinated, consolidated, prioritized and apolitical national commitment, with seamless partnerships between the private and public sectors, including universities and health care systems.

Pearl Harbor did demonstrate that once engaged, the citizens of this country have the determination it takes to defeat any enemy whether visible or invisible. I truly hope that when this COVID-19 pandemic passes, we will have the political willpower to better prepare the country and, hopefully, avoid the next crisis.

---

Tom Giannone is a principal in Avison Young’s Occupier Solutions group in AY’s New Jersey office and is a founder of its Life Sciences Specialty Practice Group.