Is Your Board Capable Of Overseeing IT?

By Gail Dutton, Contributing Writer

Follow Me On Twitter @GailLdutton

Life sciences companies are at a crossroads, although they may not recognize it. Information technology is transitioning from a tool to a strategic element that contributes to business success. Most boards, however, are ill-equipped to guide this transformation.

“There’s an interesting dynamic now in which technology is permeating every aspect of organizations,” says Patricia Lenkov, president, Agility Executive Search. “Every company, including biopharma, has an opportunity to leverage IT strategically. IT people feel boards don’t really understand that.”

They’re not wrong. Multiple studies indicate board members want more information but, trained in finance or science, often don’t know what to ask to ensure satisfactory oversight. To compound the challenge, the average age of board members is just over 63, according to the 2016, multi-industry PwC study, “Directors and IT.” This means many entered the workforce when slide rules were more common than calculators, and computers meant mainframes. PwC concludes, “This means many directors are uncomfortable overseeing their company’s IT.”

Less than one-third of the 800 PwC study respondents were confident their companies’ approaches to IT provided the board with adequate information to manage IT risks and opportunities. Board members clearly want to better comprehend the risks and opportunities related to IT. To do that, someone on the board should have more than merely a basic understanding of how IT is used in the company and how it can be used to capture opportunities.

“It is impossible for all board members to have a granular understanding of IT architecture and design, but members should have sufficient knowledge to fulfill their fiduciary duties,” says Richard A. Brand, CFO, BeyondSpring Pharmaceuticals, a clinical stage biopharmaceutical company.

WHAT BOARDS DON’T UNDERSTAND

One of the most common IT misperceptions among board members, according to the PwC report, is a belief among more than two-thirds of respondents that their company’s web and mobile applications are assessed for potential threats before being deployed. In reality, IDG Research reports that 62 percent of applications are never checked for vulnerabilities before deployment.

Another misperception, Lenkov says, is the belief that technology can be discussed separately from the business – that it’s not strategic and can be siloed. In reality, IT handles more than email and data storage. Today, it is integrated throughout organizations, affecting operations, competitive intelligence, marketing, logistics, and every other function.

Also, Lenkov adds, “Board members don’t know what they don’t know.” This often becomes evident when discussing cybersecurity. After major cyber breaches at Home Depot and Target a few years ago, boards began to realize that all companies and all industries are vulnerable to cyberattack, but they didn’t understand how or why their own companies were vulnerable. In the case of Home Depot and Target, the attacks were launched through air handling equipment’s SCADA [supervisory control and data acquisition] systems, which were assumed to be irrelevant to IT security.

One way to minimize such misperceptions is to allocate a board position to someone who can ask the right questions and also understand the answers and their implications. In this way, board oversight of the organization’s IT operations may be assured.

WHAT THE BOARD SHOULD KNOW ABOUT IT

IT involves far more than it did even five years ago. Rather than just ensuring data integrity, storage, and communications, new technologies are coming online that support accurate, near-real-time data acquisition and digital health initiatives that bring drug developers closer to patients. As IT investments become more strategic, governing boards need to understand them.

Overseeing IT at the board level doesn’t require granular expertise, but it does imply more than cursory knowledge. Instead, “Boards need some modicum of awareness of the facility and the possibilities, the willingness to include IT in a budget, and knowledge of competitive pricing for IT elements,” says James Manuso, Ph.D., president, CEO, and vice chairman of the board of directors, RespireRx Pharmaceuticals. “As a board member, you’re asked to improve budgets, but if you don’t appreciate the importance of protective measures both intra- and extracorporately, you may see those measures as unnecessary or unimportant.”

Brand explains that a board should determine whether cybersecurity insurance coverage is needed to protect the company financially if an IT breach occurs, regardless of whether that breach affects clinical operations or other strategic, management, and financial activities, and whether strong safeguards are in place. Boards also should be concerned with how electronic information is maintained and what steps have been taken by management to ensure a smooth transition to back up operations when an IT service interruption has occurred.

“To fulfill its fiduciary responsibility, a board needs to perform due diligence on third-party service providers on an ongoing basis,” Brand continues. “This includes obtaining annual compliance reports from the provider regarding the systems, controls, and responsibilities of that organization.” Some concerns may include whether the IT provider has, and exercises, a business continuity plan, and whether it is in compliance with relevant regulatory agencies regarding data protection and patient privacy. While the board should ask such questions, someone on the board also should be able to evaluate the details of the responses.

In addition to some familiarity with cybersecurity and liability for breaches, board members should also appreciate the evolving, increasingly strategic opportunities IT offers for strengthening corporate intelligence, sales, and other areas. This necessitates some familiarity with the relative merits of various platforms (such as virtual computing or public versus private clouds), the opportunity costs of maintaining legacy systems, as well as the knowledge to assess the true cost of various vendors. (For example, some vendors own the database your data populates, hampering your ability to change vendors because without that database, the data is unstructured. This is called vendor lock-in.) Benchmarking IT spending compared to competitors also may provide valuable insights.

IS ON-BOARD INSIGHT A DISTRACTION?

Boards typically address such concerns through presentations by vendors, consultants, and in-house IT specialists. “Many boards feel they understand as much as they need to through occasional briefings,” Lenkov says. That reliance on external expertise negates real oversight, however. It is the equivalent of reading a financial report without the expertise to interpret it.

Manuso disagrees, saying, “Actually having IT expertise on the board is pushing the envelope unless that person also has extra expertise that’s of unique value.” IT expertise may be valuable on the board, he says, if the company relies heavily on next-generation computing systems that advance competitiveness or that expertise is critical for strategic, operational, or financial decisions. That’s not yet common with pharma, although Big Data, predictive analytics, and digital healthcare may change that.

Particularly before commercialization, companies may be better off filling the board with experts to guide them through clinical trials and regulatory hurdles. “As long as the executive team has granular IT awareness,” Manuso says, “filling a precious board seat with an IT expert may be a distraction.”

That changes when the company develops an external sales and marketing strategy. At that point, the lack of IT expertise on the governing board may compromise directors’ ability to exercise adequate oversight.

Vertex Pharmaceuticals, with R&D and commercial offices on three continents, added IBM executive and global IT thought leader Yuchun Lee to its board in 2012 to provide that oversight. As Jeffrey Leiden, M.D., Ph.D., chair, president and CEO, said at Lee’s appointment, “Companies must provide both reliable real-time information and innovative products.” By appointing Lee to the board, Vertex can do both.

WHAT TYPE OF EXPERTISE IS BEST?

“Although technical presentations should be at a level all directors can understand, having a true expert on the board to grasp implications that aren’t obvious to those not in the field can be very beneficial,” Lenkov insists. Likely candidates include executives from technology companies, as well as the CIO or chief technology officer.

The type of technology expert matters. “A technology CEO understands how technology can be harnessed to push the company forward to reach its goals,” Lenkov points out. This executive is likely to understand industry best practices and broad challenges for a range of technology solutions. Current industry knowledge is imperative. Therefore, even recently retired executives are likely to be outdated.

The company CIO or CTO is an alternative to placing a technology company executive on the board of directors. These executives understand technologies and their interdependencies at a deep functional level.

“Today’s CIO and CTOs are strategists. They make big technological decisions and understand, tactically, what technology can do for a company,” Lenkov says. CIOs would point out that they run businesses within business and, like the CFO, are partners in strategy development. The downside, however, is that this executive is asked, essentially, to oversee him- or herself.

TECHNOLOGY COMMITTEES ARE EMERGING

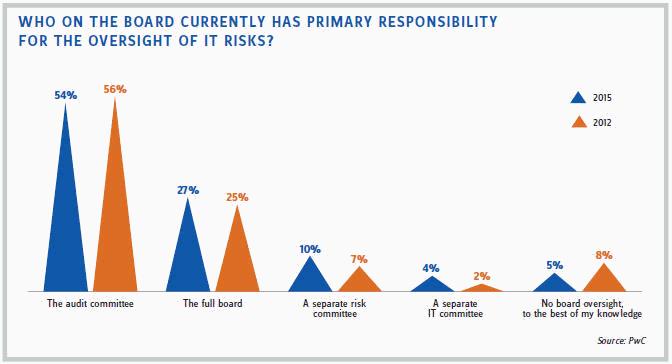

Typically, the board’s audit committee oversees IT, according to the PwC study. As companies realize the critical nature of technology, some are creating a separate committee specifically for technology. This implies the shifting of IT concerns from risk – a main audit committee issue – to opportunity.

“Technology committees aren’t overly common,” PwC analyst Barbara Berlin notes. Overall, only 4 percent of boards in the PwC study had technology committees. Among pharmaceutical and biotech companies, only a few (including Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Teva Pharmaceuticals) have established science and technology committees to provide strategic advice on the company’s direction regarding technology and R&D and their implications for the organization. In other industries, board-level technology committees also exist at Novell, Procter & Gamble, FedEx, and JP Morgan. They are only slightly more prevalent than boards that include IT expertise.

Information technology is beginning to confer a competitive advantage. Depending on their stage of development, life sciences companies should consider the relative merits of having one board member well-versed in new and emerging opportunities that technology makes feasible.

For clinical-stage companies, board-level IT expertise may be a distraction. For large pharmas, however, it may be a necessity, providing the blend of business and technical insights that helps forward-thinking companies leapfrog peers and gain market share.