Jeff Albers' Blueprint For Blueprint Medicines

By Rob Wright, Chief Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @RfwrightLSL

Jeff Albers may be the president and CEO of Blueprint Medicines — a $4 billion biopharma focused on genomically defined cancers, rare diseases, and cancer immunotherapy — but he hasn’t forgotten what it feels like to “carry a bag.” In fact, Albers is quick to credit his successes as a company leader to his breadth of experience throughout his career. For example, the years he spent as a Pfizer sales rep taught him a lot about humility. “Being a sales rep is really hard, and I don’t think most people truly appreciate that,” he reflects. “You’re faced with a remarkable amount of rejection. Plus, it’s like you’re on an island; information flow from corporate can be challenging and/or infrequent, which often leaves you with no choice other than to just figure out on your own any challenges you face.”

Throughout our conversation, which focused on his approach to ensuring that Blueprint is commercial-ready, should it garner some pivotal FDA approvals, Albers would interject with other lessons he’s learned over the years that have helped prepare him for his current position. He mentioned how, as a sales rep, you must be a self-starter who is persistent and good at prioritizing. Other experiences that formed the building blocks of his leadership style include five years as a corporate life science attorney, six years at Genzyme in senior roles, and more than two years as the U.S. president for Algeta ASA before it was acquired by Bayer in 2014. “You learn the importance of being empathetic and a transparent, succinct, and clear communicator,” he says. “At Blueprint, whether in the field or the home office, we want employees to have a sense of why we’re doing what we do, so I always try to share as much information as broadly as possible.” Lately, that information has revolved around how and why the company is building a commercial business unit.

PREPARING FOR A NEW BUSINESS FUNCTION

Albers arrived at Blueprint in 2014 with a very commercial-focused background, which was odd considering that, at the time, the company was still a pure research organization. But as he began meeting Blueprint’s people — from bench scientists to board members — he got a good feeling about where it was heading. Plus, as he reviewed the company’s target product profiles in development, he thought, “If these molecules behave in humans as they did in animal models, there could be an accelerated path to approval.” That meant that it would have accelerated timelines on several fronts, including commercial readiness. “I thought I could make a difference and could learn, so that’s why I joined,” he says with a smile.

He knew that to build the commercial function at the company, he and his team needed answers to many of the same questions you would ask when constructing any other function within a biopharma. For example:

- How much information do you need before you commit to developing this new department?

- What’s the scope of that build?

- Can you do it incrementally, or do you have to build out a whole function at one time?

There were also some basic questions they needed to answer early on to make sure everyone was on the same page, especially when it came to hiring staff for this new function. Some of those questions included:

- What are you trying to build?

- What product are you trying to bring forward?

- What type of molecule is it?

- What’s the target product profile?

- What’s the initial patient population?

- How do you think you’re going to get to mechanistic proof-of-concept?

- What’s the first indication?”

THE FIRST HIRE WILL SEND A MESSAGE

“My advice to CEOs of smaller biopharma companies is: As early as possible, start building some components of your commercial function,” states Albers. “I don’t mean just marketing or sales, but positions requiring a long-term view. You want as many different functions weighing in on your programs as early as possible.” Why? Because manufacturing needs to have a sense of what’s coming, and clinical teams need insight into how a product is being designed, and for whom. They all need to know this type of information, not just for the first trial, but for how a program will evolve over time to maximize the number of patients appropriate for the therapy. “When things get handed off as if people are in silos, opportunities can be completely missed, which, in my opinion, tends to happen less frequently when cross-functional people are talking together early on.”

Keeping all of that in mind, he knew that as the new CEO the first person he hired would send a message to the rest of the organization regarding his commitment to building the commercial function. He also knew he wanted someone with a science background because, “Biology is humbling, and things go wrong all the time, so you need someone who can take a long-term view when assessing a problem.” The person would need to be capable of accurately assessing a first opportunity and figuring out what it would take to ultimately deliver a therapy to patients. What would the product life cycle management look like? How would the company grow from that first opportunity? Is the opportunity around combinations, diseases, or geographic reach? These are the types of questions he had to consider just 30 days into his new position, because that’s when he hired Philina Lee, Ph.D., as VP of commercial strategy and operations.

Lee, who completed her Ph.D. in cell biology at MIT, had worked with Albers at Algeta. As such, Albers was confident she was the right choice to lead the company’s market development and new product commercialization strategic planning for investigational medicines. Though currently charged with marketing, patient services, and U.S. precision medicine initiatives, Lee proved instrumental in helping to lay the foundational elements for Blueprints’ eventual commercial organization build (e.g., sales and marketing, market access, reimbursement, and medical affairs). But what the company needed next was a sales force.

BUILDING A DIFFERENT KIND OF COMMERCIAL ORGANIZATION

The medicines that Blueprint creates are highly targeted and, therefore, require a highly targeted field sales force, which the company plans to own, not rent. “We’ll hire full-time staff, so they are fully committed to just us, which is how you build a company for the long term,” explains Albers. Although the company hasn’t disclosed what the sales force’s “footprint” will look like, Albers says they will look for opportunities for overlap with different therapies, both in the EU and U.S. “When building a sales force, you want to have the necessary team in place for the initial approved indication, while also having some level of preparedness for subsequent indications or assets. You want to start with one size too small, and then add additional resources as you hit certain trigger dates, so as not to overwhelm the company with costs.”

The company is placing a premium on attracting talent with breadth and depth of experience in oncology or rare diseases. In addition, Albers says the best candidates also will be good collaborators, especially with the staff at the home office. That’s why Blueprint has been involving its scientists in the commercial-build interview process. “It’s been a bit of a shock to the system for those being interviewed and, in some cases, to the interviewers as well,” he says. To keep that cross-collaborative mindset going, the company also has weekly science meetings that are open to all employees, in which they talk about earlier-stage projects to provide a sense of what is coming down the road.

And lately, there’s been a lot to talk about. According to the company’s “2020 Blueprint” strategy, released early last year (i.e., Jan. 2019), the following will be expected to be achieved by the end of 2020:

- 2 marketed products in the United States and 1 marketed product in Europe

- 4 additional marketing applications pending in the United States and Europe

- 6 therapeutic candidates in global clinical development

- 8 research programs that leverage strategic areas of focus

Of course, we all know, that when it comes to drug development, there are no guarantees, and building a commercial engine is a risky proposition. Albers, though, likes their chances. “If we were looking at just one indication, we might be a little more cautious, but it’s not like we are going to build as if each one is going to hit at once; it’s more of a staged approach. When I speak with investors, I tell them that they should never invest in Blueprint based on one program. The value of this company is that we can find efficiencies across programs. Responsible discovery begets responsible drug development, which begets responsible commercialization.”

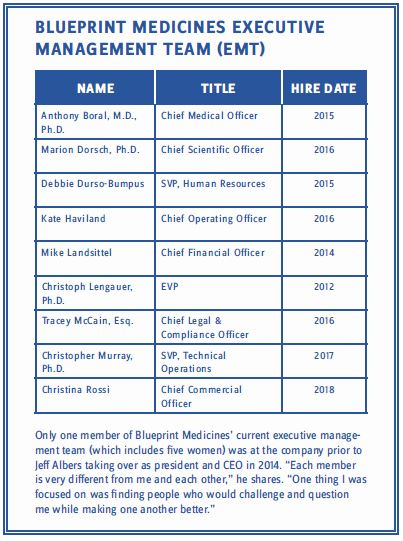

Albers’ confidence in the future of the company stems, in part, from his past experiences, but also from what he has managed to accomplish in the last six years. Since arriving, he has helped create a cross-collaborative corporate culture at the company, overseen the receipt of four FDA Breakthrough Therapy designations, built one of the most diverse leadership teams in all of biopharma (see table below), and taken the once small, private company through an IPO (NASDAQ: BPMC) that has seen its value skyrocket to roughly $4 billion! Not bad for a former drug rep. Not bad at all.

Sidebar 1

EMPLOYEE SELECTION AND RED FLAGS

The process of building Blueprint Medicines as a company involves, among other things, hiring a lot of staff. It’s a process in which Jeff Albers is highly involved. “We try to evaluate people in terms of their transparency in communication. For example, are they a clear communicator and open to a diversity of views? When interviewing a candidate, if they ramble on and on about themselves, that’s a red flag to me.”

Albers stresses that biopharma is a “team sport” that requires people with different backgrounds, since no one knows how to do it all. As such, Blueprint looks for candidates who have past experiences demonstrating their willingness to collaborate.

Albers continues to meet with every new hire in person, and when doing so, offers the following advice. “My expectation for you is to come in here and be better than everybody else at something, and I tend not to care exactly what that something is. But I then expect you to be humble enough to recognize that everyone else here is, therefore, better than you at something. So, share your expertise and listen to theirs.”

Sidebar 2

DON’T TAKE YOUR VENDOR RELATIONSHIPS FOR GRANTED

When reflecting on his biopharma career, Jeff Albers, president and CEO of Blueprint Medicines, attests to making plenty of mistakes, but he tries to make sure under-communicating isn’t one of them. For example, not long after joining the company in 2014, he noted that the company was down to very little money. At the time, the company was building its chemical library, and the process took longer and cost more than anticipated. But the company was able to get through that period without destroying the trust it had built with its vendors. A key component to doing that involved transparent communication about where they were with financing, even going so far as to share term sheets with some of its vendors. “Some of these vendors have since become our strongest partners,” the CEO notes. Good thing, because as Blueprint moves ever closer to having an FDA-approved commercial asset, the plan for manufacturing involves outsourcing. “We understand that we have a variety of stakeholders who have placed their trust in us, which includes CMOs that we work with across our portfolio. And given the speed with which we’ve been moving, which is only made more challenging with the various breakthrough therapy designations received, we realize that every outsourced manufacturing run is incredibly important, so we don’t want to take any of those relationships for granted,” he concludes.