7 Lessons In Supply Chain Management Learned From COVID-19

By Rai Chowdhary

Whether you are sourcing APIs, excipients, medical devices, drugs, or bed capacity in hospitals, your supply chain is key to delivering successful outcomes.

Whether you are sourcing APIs, excipients, medical devices, drugs, or bed capacity in hospitals, your supply chain is key to delivering successful outcomes.

The age-old challenge is to balance capacity vs. demand; however, as a result of the current coronavirus (COVID-19), we find ourselves deficient yet again. But introspection opens the doors to learning. So what did we miss? Where did we go wrong? Here are seven lessons in supply chain management we’ve learned early (article written in late March 2020) in this pandemic.

1: Missing or ignoring signals

The news about COVID-19 did not strike like a bolt of lightning. It had been circulating since December 2019 with an increasing drumbeat. It also was known that this is a new strain, one for which neither a cure nor a vaccine exists. The fact that Chinese authorities imposed a lockdown of Wuhan (a city with a population bigger than New York) was a key signal that supply chains would potentially be disrupted. Was this signal missed or ignored? Regardless, the impact to supply chain was imminent.

2: Sense of invincibility

We as a species tend to believe that we will stay unaffected, discounting the signals. While such thinking may be born from our survival instinct, it is often misplaced. It results in delayed action, until the wolf is at the door. Trouble is, remedial action such as moving supply sources from one location to another takes time, can be quite difficult, and is fraught with the risk of negative impact on quality and delivery.

3: Blinded by cost competitiveness

In the relentless drive to reduce costs, focus shifts heavily toward the lowest-cost provider (or region) and away from creating a robust supply base. The extent of single-sourced suppliers across the life sciences industries is palpable and inexcusable at the same time. Savvy companies engage in (and bear the cost of) supplier development to prevent overreliance on one source. Reclassifying this cost as an investment in business continuity or insurance makes it easier to swallow.

4: Fire drills and stress testing the supply chain

While fire drills for employee safety are routinely conducted by most firms, they are rarely, if ever, conducted on the supply chain, even though it is the key artery for goods and services. Assessing where the vulnerabilities and constraints might lie acts as a vaccine against quality and delivery risks. These assessments need to span the whole supply chain — from sub-tier suppliers to the point of use. Conducting supplier audits (as is the predominant practice) in lieu of this approach leaves a vast amount of risk unmitigated.

5: Pace of scalability and adaptability of the system

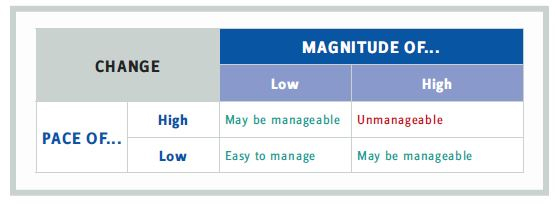

Change is only one aspect of a dynamic system; pace of change is another. Adaptability of the system plays into this equation, as well. It is a measure of how rapidly supply resources can be shifted from one location to another.

An examination of the supply chain using a simple 2x2 table (see next page) can quickly highlight the ability of a system to handle different types of changes. The worst combination would be when high pace of change, high magnitude, and low adaptability exist simultaneously.

6: Price stability in face of changing demand

One of the worst things that can happen during demand surges — particularly due to natural calamities — is price gouging of supplies and services. Recently, prices of face masks jumped from approximately $0.80 to nearly $4.00 due to high demand as the corona pandemic spread across the nation. While supplier agreements can play a significant role in managing this, often they are bereft of clauses to this effect.

7: Silos and impervious walls

A sad fact of corporate life is that job functions are grouped or defined along the lines of educational disciplines such as marketing, accounting, engineering, and manufacturing. While this is convenient it adds labels that become restrictive and creates identities that promote silo-based thinking. This is further reinforced when functional heads are held accountable for their “departmental budgets.” The result is thick silo walls that reduce or choke vital information exchange and lead to suboptimization at the cost of the whole. For example, in the interest of cost savings, Purchasing may be driven to source material from a low-cost supplier repeatedly, which then causes other suppliers to disengage, leaving the company vulnerable to reliance on a single source and its associated risks.

In conclusion, although the above missteps have happened before to varying degrees, the question remains as to why lessons were not learned and implemented. The current coronavirus situation is yet another wake-up call, perhaps to remind us to slow down a bit and study from nature itself. Species that learn to survive on a diverse diet can withstand the vagaries of nature better than others.

RAI CHOWDHARY is the CEO of KPI System (Key Performance Improvement), a consultancy serving the life sciences, food, aerospace, automotive, and energy industries.