Pet Medicines: Smaller Market, Lower Costs, Greater Margins

By Ed Miseta, Chief Editor, Clinical Leader

Making the move from a pharmaceutical firm to an animal health company might seem like taking a small step from one drug discovery organization to another. But that transition process for one executive was a bigger challenge than he expected, and now it has him looking at the drug discovery process in a new way.

After receiving his doctorate from Harvard Medical School, Richard Chin began his pharma career by serving as medical director at P&G Pharmaceuticals. That was followed by stints at Genentech, Elan Pharmaceuticals, Oxigene, and a few other firms working on drugs for arthritis, asthma, and eye diseases. But as an animal lover, Chin was always thinking about ways in which he could use his pharma experience to improve the lives of pets.

Chin first met Denise Bevers while both were working at Elan. They quickly discovered their mutual interest in the health of animals. “After discussing the opportunities that existed in the area of animal health, we considered starting a veterinary company,” says Chin. “Unfortunately, we did not have a breakthrough idea at that time, so the idea was put on hold.”

FROM ANIMALS TO HUMANS, AND HUMANS TO ANIMALS

Chin eventually moved on to other companies, later landing at an organization called the Institute for OneWorldHealth. OneWorldHealth, funded primarily by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, develops low-cost drugs for impoverished patients in developing nations. While leading that organization, Chin realized that many of the drugs used on patients in third-world countries had originated with drugs developed for livestock. That led him to wonder if drugs developed for humans could be used on animals. “Pharma companies have spent billions of dollars developing drugs for humans that are not available for animals. Many were for human diseases that I knew also existed in animals, such as diabetes, osteoarthritis, lupus, inflammatory bowel disease, and various forms of cancer. The diseases also tend to be similar in humans and animals. That was the genesis of our company.”

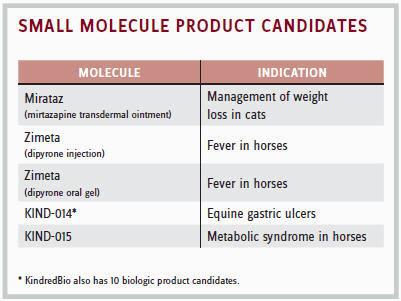

Chin reconnected with Bevers, and together they cofounded KindredBio, where he is now the CEO and she serves as COO.

“This is a new field, and it almost feels weird to call it new considering how long humans have had animals as pets,” says Chin. “But one trend that is relatively new is the idea of pets being looked at as members of the family. That trend has been in existence for only the last 15 or 20 years. Today, people spend more on pets than ever before and will search for medicines to cure their diseases, just like we do for humans.”

![]()

"We have not seen the price escalation that has occurred in clinical trials for human drugs."

Richard Chin

CEO, KindredBio

AN OPPORTUNITY AND A CHALLENGE

Although animal health is a burgeoning market, Chin and Bevers found the newness of it to be a challenge when launching the company. “Investors understand the pharma industry,” says Chin. “They understand human diseases, and they understand the process of getting a new drug approved and commercialized. But when it comes to animal health, it’s a different story. When I first starting talking to them, I found they didn’t understand the regulatory pathway for animal medicines and didn’t understand what the market for these drugs looked like. That required us to do some educating on these medicines.”

They would explain that the market size is 10 times smaller for animal medicines than it is for humans. They also would note that a $100 million drug is considered a blockbuster in animal medicine. But the flip side of that is that the cost of developing animal medicines is 100 times less than for humans. “A new animal drug can be developed for $5 million or less, whereas the cost of developing a new drug for humans can be $1 billion or more,” he says. “There are also far fewer companies producing medicines for animals.”

They would explain that the market size is 10 times smaller for animal medicines than it is for humans. They also would note that a $100 million drug is considered a blockbuster in animal medicine. But the flip side of that is that the cost of developing animal medicines is 100 times less than for humans. “A new animal drug can be developed for $5 million or less, whereas the cost of developing a new drug for humans can be $1 billion or more,” he says. “There are also far fewer companies producing medicines for animals.”

HUGE SAVINGS ON TRIALS

When developing a new drug for humans, clinical trials are a huge cost-driver. On the animal side, it is also the area where a large portion of the savings is accrued. First, the studies are much smaller. Rather than performing two Phase 3 studies that include thousands of human patients, veterinary studies require only one pivotal study and a minimum of 100 animals exposed to the drug. The per-animal cost is also a lot lower than the cost of including a human in a trial, and the trials tend to be shorter. According to Chin, the maximum length of a study is around six months, but many will be complete in less than 30 days.

“In human drug development, it is not unusual to spend between $50,000 and $100,000 per patient participating in a trial,” states Chin. “In the veterinary medicines field, the cost is around $5,000 per patient. The studies are shorter, the cost of veterinarians tends to be less than the cost of a human physician, and we have not seen the price escalation that has occurred in clinical trials for human drugs.”

Chin notes that 20 years ago, pharma companies could still conduct a human trial for $5 million to $10 million. “Today you can’t perform one for anywhere near that price. With animal medicines, you still can. Many Phase 3 studies are generally performed at a cost of less than $1 million.”

The field of animal medicines could include both family pets and livestock. When starting the business, Chin and Bevers opted to focus on family pets and horses (which are also close companions to their owners). As Chin explains, livestock is a very different market than pets. Even though both involve animals, the drugs are very different.

In the pet market, drugs are developed to treat therapeutic diseases, just like in humans. With livestock, most of the drugs on the market are vaccines, antibiotics, and hormones that speed growth in animals. That drug business is high-volume and low-margin, which is not the market Chin wanted to enter. “Our expertise lies in treating diseases,” he says. “That is no longer a growth area in livestock.”

A SIMILAR REGULATORY PATHWAY

In the area of pet medicines, Chin estimates more than 80 percent of therapeutics are regulated by the FDA (topical treatments such as flea drops are regulated by the EPA). For that reason, the regulatory pathway is similar to what it is for new human medicines. A randomized, controlled study must be used to show that a new drug is both effective and safe.

“If we develop a drug to treat dermatitis in canines, we would find dogs that have the condition,” notes Chin. “The veterinary clinics participating in the study would be provided with the protocol and the medicine. Sites are monitored in a manner similar to clinics taking part in a human study. With animals, informed consent is obtained from the owner of the pet, and there are inclusion and exclusion criteria that must be met. Dogs selected for participation will then be randomized and receive the drug.”

One thing that KindredBio is able to cut out of their discovery process, which further reduces their development costs, is rodent studies. The reason for this is that any drugs they test on animals are coming from pharma companies developing treatments for humans.

“These drugs have already been tested on animals for safety and efficacy before ever being used in humans,” adds Chin. “In fact, I like to joke that humans are the preclinical species on which medicines are tested before being administered to pets. Our clients and veterinarians seem to get a good laugh out of that.”