Repeal & Replace Confronts Trump's Base

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

To understand the political peril Republicans confront in their effort to repeal and replace Obamacare, it is worth noting that many of the areas that gained the most coverage from Obamacare are the working-class districts carried by President Trump with the largest margins. Gallup polling found that counties characterized as “Working- Class Country” gained the most health insurance coverage since 2008 — 6.8 percent — and were carried by Trump by a 46 percent margin.

Conversely, a January CNN poll found the 18 to 34 age demographic group supports Obamacare by the widest margin (59 percent favor and 38 percent oppose), yet it is that same demographic that has refused to participate in the exchanges, a key factor making the risk pool for insurers fundamentally unworkable and leading to a mass exodus of plans. The individual mandate, which Republicans seek to repeal, cannot compel enough young people to purchase coverage for an underlying policy they profess to support.

The Republican “Repeal and Replace” legislation, known as the American Health Care Act working its way through the House, would sunset Medicaid expansion, which has provided coverage to 11 million low-income Americans, in 2020. While just 31 states opted for the 90 percent federal match to cover additional populations of nondisabled adults, they included West Virginia, Ohio, Michigan, Kentucky, Indiana, and Arkansas, all of which Trump carried.

CBO’S TORTURED ASSUMPTIONS ON THE UNINSURED

Shortly after the House Energy & Commerce and Ways & Means committees worked through the night in marathon sessions to approve the American Health Care Act, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its analysis of the legislation’s impact on coverage — debilitating at first glance but rather sanguine when the underlying assumptions of its estimates are unpacked. The headline hoopla: CBO predicts that 14 million more individuals would be uninsured in 2018, rising to 24 million in 2026 under the GOP plan.

Problem #1: CBO’s fixation on the individual mandate.

CBO says most of the initial group would immediately drop coverage due to repeal of the individual mandate. This figure includes 5 million Medicaid enrollees who are too poor to pay taxes (and therefore the mandate penalty), but whom the CBO curiously believes would abandon free healthcare due to the absence of a mandate that has never applied to them.

Problem #2: CBO’s use of faulty baseline assumptions.

▶ When the ACA was enacted, CBO projected twice the number to be in the insurance exchanges as are actually enrolled today. Despite the recent mass exodus of plans (leaving only one plan in 40 percent of the counties) and relatively flat enrollment since 2015, the CBO baseline still projects the number of people enrolled in exchange plans to increase by 8 million, or almost 75 percent. Since CBO predicts the Republican plan will result in continued flat enrollment — POOF! — the GOP plan will mean 8 million people losing coverage (despite never being enrolled).

▶ Despite seven years of heated debate and thorough contemplation of the fiscal and human implications of expanding Medicaid, 19 states have chosen not to do so, yet CBO believes the vast majority of those remaining states will do so shortly. This results in another 2 to 5 million “losing” coverage they do not now have.

MIDDLE AMERICA’S CHALLENGE: NON-WORKING ADULTS

Medicaid’s critical growing role of providing health coverage reflects a broader demographic trend that is plaguing the country — the absence of work, and therefore work-related insurance coverage — in huge swaths of the population. In 2013, the Census Bureau found that over one-fifth of all men between 25 and 55 are on Medicaid; and of the non-working male Anglo population, 57 percent were collecting one or more government disability benefits.

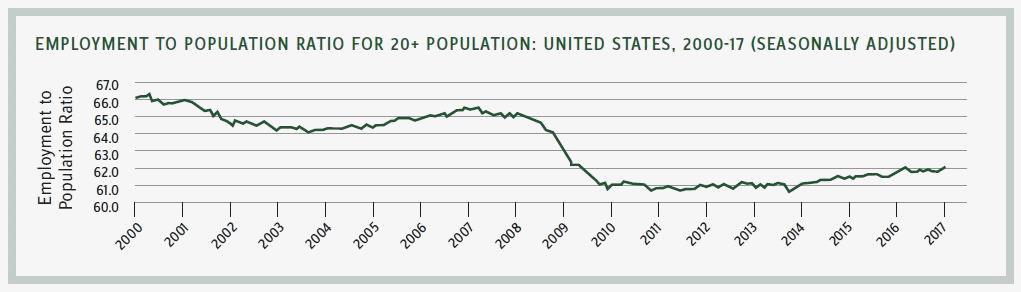

In a seminal essay in Commentary Magazine, Nicholas Eberstadt observed, “Work rates have fallen off a cliff since the year 2000 and are at their lowest levels in decades.” Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the overall work rate for Americans age 20 and older plunged nearly 5 percentage points (from 64.6 to 59.7).

Eberstadt concludes, “Postwar America never experienced anything comparable.… From peak to trough, the collapse in work rates for U.S. adults between 2008 and 2010 was roughly twice the amplitude of what had previously been the country’s worst postwar recession back in the early 1980s. In that previous recession, it took America five years to re-attain the adult work rates recorded at the start of 1980. This time, the U.S. job market has as yet, in early 2017, scarcely begun to claw its way back up to the work rates of 2007 — much less back to the work rates from early 2000.”

This hollowing out of the workforce explains much of the electorate’s angry populism that drove Donald Trump to the White House and also created resonance for socialist senator Bernie Sanders in the Democratic primaries, despite the soaring stock market and Washington’s characterization of low unemployment rates, which exclude those not actively looking for work.

Nearly half of labor-force dropouts — 7 million in total — are addicted to opioids, often with tragic consequences. A 2015 report by the Drug Enforcement Administration found that more Americans died of drug overdoses (largely related to opioid abuse) than from either traffic fatalities or guns.

Medicaid has both financed this plague by covering almost the entire cost of prescribed opioids (which are often resold on the black market for thousands of dollars) and provided important treatment and rehabilitation for the addicted. Could requiring states to take more responsibility for Medicaid spending result in more stringent controls to deter opioid abuse, or will it lead to the gutting of critical drug addiction treatment programs? That remains unclear.

What is clear is that Donald Trump did not win the White House by threatening to gut the social safety net. Rather, he appealed to middle America by promising to deliver a better, more productive and prosperous life to hard-hit communities that are increasingly in despair. The slow-rolling collapse of Obamacare presents an opportunity for President Trump and the Republican Congress.

But now is not the time for unserious, philosophical dogmatism. Rep. Mark Meadows (R-NC), leader of the far-right “Freedom Caucus,” dubbed the American Health Care Act “Obamacare Lite” and construed the refundable tax credit as a new entitlement that freedom-loving conservatives could not support. Yet Meadows and about one-third of the Freedom Caucus cosponsored then Rep. Tom Price’s Empowering Patients First Act, which featured — you guessed it — a refundable tax credit. Indeed, refundable tax credits have been a key feature of all Republican health reform legislation for more than a decade.

But how can a $2,000 to $4,000 refundable tax credit for health insurance be enough for an individual making $20,000 a year? Avik Roy, president of the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, says the American Health Care Act “isn’t flawed because it offers financial assistance to the uninsured. It’s flawed because it doesn’t provide enough assistance to them, making premiums unaffordable for many poor people.” He suggests changing the flat credits that vary only by age to be greater for those with lower income and gradually decline as income rises.

That would be a positive change for the voters that propelled President Trump to the White House.