The Myth Of Disruptive Innovation In Clinical Trials: Time For A More Disciplined Approach

By Beth Harper

At the outset, let me state for the record that I’m a big advocate for change. My threshold for accepting “that’s the way we’ve always done things” is actually quite low. But I confess that I’m getting a bit dizzy, dismayed, and, to be frank, disappointed with all the so-called “disruptive innovation” taking place in the industry. First and foremost, I don't really think that anything taking place really qualifies as disruptive.1 Second, with all this disruption, we haven’t really changed any key performance indicators (KPIs) like trial participation rates or clinical trial cycle times. Third, I fear that the more we collectively get distracted by “shiny object syndrome,”2 we risk not focusing on the things that could really make a difference to getting patients much needed treatments in a more effective way. Hence, I am pushing for a change in both terminology and mind-set from one of disruption to discipline.

disappointed with all the so-called “disruptive innovation” taking place in the industry. First and foremost, I don't really think that anything taking place really qualifies as disruptive.1 Second, with all this disruption, we haven’t really changed any key performance indicators (KPIs) like trial participation rates or clinical trial cycle times. Third, I fear that the more we collectively get distracted by “shiny object syndrome,”2 we risk not focusing on the things that could really make a difference to getting patients much needed treatments in a more effective way. Hence, I am pushing for a change in both terminology and mind-set from one of disruption to discipline.

Disruptive innovation refers to a new development that dramatically changes the way a structure or industry functions. It’s been over 20 years since the term was coined and, while my opinion as to what qualifies for innovative is irrelevant, some real experts believe “the word disruption has become an all-purpose technology industry buzzword; overused, barely understood, drained of meaning…”.3 In fact, the originator of the concept of disruptive innovation notes that “the theory’s core concepts have been widely misunderstood and its basic tenets frequently misapplied.”1

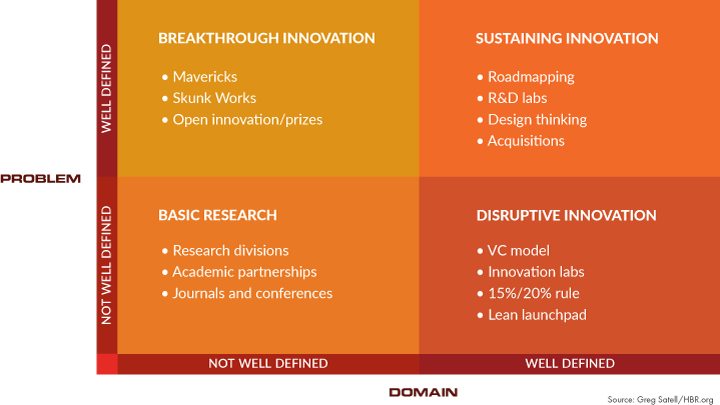

In his article on the four types of innovation and the problems they solve, Greg Satell provides an excellent visual to help distinguish different types of innovation4:

Figure 1: Four types of innovation (source: Greg Satell/HBR.org)

What’s even better about this article is that it connects the dots between innovation and problem solving. In fact, he believes that innovation, at its core, is about solving problems and that innovation should be viewed as a set of tools designed to accomplish specific objectives. I would argue that we have many problems to be solved in drug development and these aren’t a surprise to anyone. It’s also no surprise that drug development cycle times haven’t changed in the last 20 years, the percentage of drugs that fail has actually increased, the likelihood of achieving regulatory approval for most drugs is less than 20 percent, and just about every trial performance metric captured by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (TCSDD) has stayed the same or worsened.5 Sure, we all know that protocol complexity is to blame for some of these trends, but with all of the innovations purported to be taking place, one would expect some indication that they are actually helping to accelerate the development and approval of new treatments.

Back to Satell’s model: A good case can be made that we aren’t really about disrupting the industry, but most of our efforts are about sustaining innovation, or getting better at what we do. Whether we are discussing AI technologies, patient-centric initiatives, or use of mobile devices or apps, by definition, none of these actually meet the true definition of disruptive innovation, as to date none have dramatically changed the way we function. Nor do they really have the potential to disrupt; nonetheless, these are innovations that can help us get better at what we do. But given the discouraging data from the TSCDD, it’s worth asking why these innovations haven’t fundamentally solved our problems.

My observation is that it comes down to a lack of discipline and dedication to picking and sticking to an innovation. In other words, we suffer from shiny object syndrome and get distracted with the next latest technology because we get bored once we appreciate the operational hurdles we have to overcome to get any of these innovations adopted. Consider a couple of patient-centric initiatives that have the true potential to enhance trial participation — eConsent and logistics support for subjects.

Inconvenience, travel, and logistics issues have topped the list of barriers to trial participation for decades.6 Regardless of the nature, number, or sources of the surveys, the literature is consistent that some of the biggest barriers to trial participation are the inability to get to the research site, lack of access to transportation, or other related logistical issues. Patient education and informed consent are the cornerstone of clinical research and certainly anything that can be used to enhance subject understanding, and increase the likelihood of their participation, should be worthy of innovation attempts.

It’s been over 10 years since vendors have been offering reloadable debit cards, home nursing visits, and travel support for subjects and over five years since eConsent vendors emerged on the markets. Yet utilization remains very low. A 2017 CISCRP survey indicated that only 17 percent of patients reported using an eConsent in the trial they had participated in and only 7 percent were offered home health services or concierge (travel) services.7

While it’s difficult to get a true sense of the utilization of these services, some industry surveys suggest they are still perceived as costly and burdensome to implement, despite some convincing case studies with very high return on investment of these “study volunteer ease” initiatives.8 A 2016 survey reported that only 28 percent of global sites have used eConsent on at least one study, with 2 percent of sites reporting use across all studies.9 Anticipating a growing rate in adoption of eConsent, a CRF Health 2017 eConsent survey revealed less than half of the respondents estimated they would be using eConsent in 20 percent of their studies within two years.10 Hardly lightning speed innovation and adoption!

So we can’t blame a lack of available and innovative services providers. Nor can we blame regulatory agencies for an unwillingness to consider more creative solutions to address these problems. It’s been three years since the FDA issued its eConsent guidance document.11 The 2018 eConsent Landscape Study conducted by Transcelerate Biopharma revealed that 33 countries had made submissions with eConsent (although to be fair, only half the countries had implemented eConsent).12 Furthermore, the 2018 FDA Guidance on Payment and Reimbursement to Subjects was explicit in noting that “FDA does not consider reimbursement for travel expenses to and from the clinical trial site and associated costs such as airfare, parking, and lodging to raise issues regarding undue influence.”13 Regulatory excuses eliminated there!

As we approach 2020, it’s a bit mind-boggling to me that that 100 percent of trials aren’t offering some kind of logistical or travel support, that the use of reloadable clinical trial debit cards isn’t standard operating procedure for each and every trial, and that eConsent is still struggling to gain traction. What if we could make a full-fledged commitment to implementing these innovations from the last five to 10 years and resist the distractions of the next shiny object? We might get a little bored, but I have a hunch our patients would appreciate our discipline.

References:

- Christensen, C. et al. What is Disruptive Innovation? Harvard Business Review. 2015. https://hbr.org/2015/12/what-is-disruptive-innovation

- Shiny Object Syndrome: What it is and How to Beat it. https://fitzvillafuerte.com/shiny-object-syndrome-what-is-it-and-how-to-beat-it.html

- Concept of ‘Disruptive Innovation’ is Being Disrupted– Reasons to Believe, Reasons to Doubt: Innovator’s Dilemma…https://bizshifts-trends.com/concept-disruptive-innovation-disrupted-reasons-believe-reasons-doubt-innovators-dilemma/

- Satell, G. The 4 Types of Innovation and the Problems They Solve. Harvard Business Review. 2017. https://hbr.org/2017/06/the-4-types-of-innovation-and-the-problems-they-solve

- Getz, K. The State of the Industry. Data from the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development presented at the ACRP Annual Conference, April 2019.

- Ross, S. et al. Barriers to Participation in Randomised Controlled Trials: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. Volume 52, Issue 12, December 1999. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0895435699001419

- 2017 Perceptions and Insights Survey. CISCRP. https://ciscrp.wpengine.com/download/2017-perceptions-insights-study-the-participation-experience/?wpdmdl=8770&refresh=5dd16db49a30f1574006196

- Capturing the Value of Patient Engagement: Summary of Results of the 2016 Study of Patient-Centric Initiatives in Drug Development. DIA. January 2017.

- Cascade, E. Electronic Informed Consent – The Star Bench Warmer? DrugDev News. 2018. https://www.drugdev.com/about-us/news-item/electronic-informed-consent-star-bench-warmer/

- Is eConsent adoption poised to grow? CenterWatch on-line. 2017. https://www.centerwatch.com/news-online/2017/09/01/econsent-adoption-poised-grow/

- FDA guidance. Use of Electronic Informed Consent Questions and Answers. December 2016. https://www.fda.gov/media/116850/download

- 2018 cConsent Landscape Survey. https://www.transceleratebiopharmainc.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/2018-eConsent-Landscape-Assessment-Country-Overview-1.pdf

- FDA Guidance. Payment and Reimbursement to Research Subjects. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/payment-and-reimbursement-research-subjects

About The Author

Beth Harper is the president of Clinical Performance Partners, Inc., a clinical research consulting firm specializing in enrollment and site performance management. Harper also is the workforce innovation officer for the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP). She has passionately pursued solutions for optimizing clinical trials and educating clinical research professionals for over three decades. Harper is an adjunct assistant professor at George Washington University who has published and presented extensively in the areas of protocol optimization, study feasibility, site selection, patient recruitment, and sponsor-site relationship management. She serves on the CISCRP Advisory Board and the Clinical Leader Editorial Advisory Board, among other industry volunteer activities. Harper received her B.S. in occupational therapy from the University of Wisconsin and an M.B.A. from the University of Texas. She can be reached at 817-946-4728, bharper@clinicalperformancepartners.com, or bharper@acrpnet.org.

enrollment and site performance management. Harper also is the workforce innovation officer for the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP). She has passionately pursued solutions for optimizing clinical trials and educating clinical research professionals for over three decades. Harper is an adjunct assistant professor at George Washington University who has published and presented extensively in the areas of protocol optimization, study feasibility, site selection, patient recruitment, and sponsor-site relationship management. She serves on the CISCRP Advisory Board and the Clinical Leader Editorial Advisory Board, among other industry volunteer activities. Harper received her B.S. in occupational therapy from the University of Wisconsin and an M.B.A. from the University of Texas. She can be reached at 817-946-4728, bharper@clinicalperformancepartners.com, or bharper@acrpnet.org.