The Risks Of Restructuring Part D

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

Despite Speaker Pelosi’s partisan approach to prescription drug pricing legislation, the building blocks for bipartisan consensus on a redesign of Medicare Part D’s outpatient drug benefit are being laid for a possible deal in Q1 of 2020.

Despite Speaker Pelosi’s partisan approach to prescription drug pricing legislation, the building blocks for bipartisan consensus on a redesign of Medicare Part D’s outpatient drug benefit are being laid for a possible deal in Q1 of 2020.

The health policy focus in D.C. has been on a looming House vote on the Pelosi price control bill, which would cap prices of prescription drugs at an international pricing index and task the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to “negotiate” for lower prices enforced with a threat of 95 percent excise tax for failure to do so.

That vote has been reportedly delayed as the committees await Congressional Budget Office (CBO) scoring analysis. But intraparty Democratic squabbling between progressives who seek even more government control over the pharmaceutical industry and moderates who were having second thoughts about the implications for future cures may also have played a part. It is currently scheduled for mid-December.

Part D Redesign

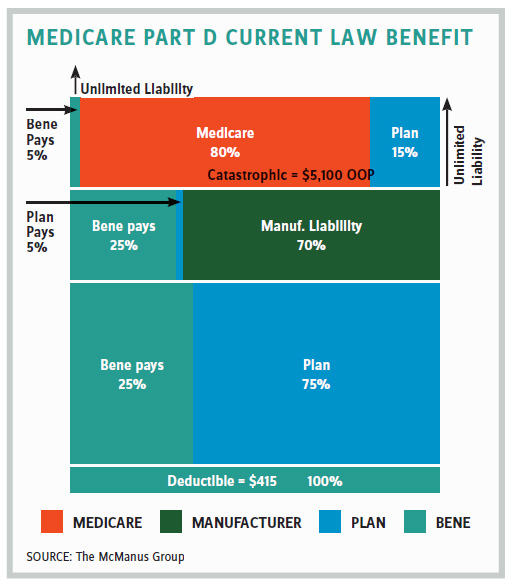

Enacted in 2003, Medicare Part D has served the country well: Costs in the first decade were 45 percent below initial projections, popularity very high, and choice of plans abundant. In a time when healthcare costs have escalated, the Part D benefit’s costs have been flat since 2015, and the monthly premium has been stable for a decade and actually declined the last three years.

Yet distortions have emerged over time, particularly after Obamacare added a 50 percent manufacturer discount for drugs in the so-called “coverage gap,” which expedited many beneficiaries into the catastrophic portion of the benefit, where 95 percent of costs are covered. In 2017, the coverage gap discounts provided by manufacturers totaled about $5.7 billion.

In 2016, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) recommended restructuring the benefit to provide more cost control for high-cost drugs, noting that spending on the benefit had shifted dramatically over time from the direct subsidy to “reinsurance” for costs when beneficiaries hit the catastrophic benefit. Indeed, reinsurance costs doubled from 26 to 52 percent of the benefit between 2007 and 2014.

MedPAC suggested dramatically reducing the amount Medicare pays through reinsurance for costs in the catastrophic portion of the benefit from 80 percent to 20 percent and correspondingly increasing the portion covered by the Part D plan from 15 percent to 80 percent. It also suggested eliminating the 5 percent beneficiary coinsurance entirely. It argued that increasing plan exposure would encourage more aggressive negotiating with pharmaceuticals on costly specialty drugs.

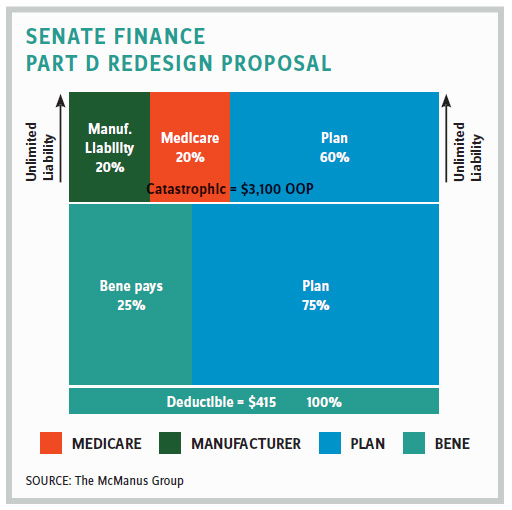

Earlier this year Aetna commissioned a study by Miliman adopting the MedPAC recommendation, but with a twist: The price control on manufacturers should be moved from the coverage gap to the catastrophic portion of the benefit. The study suggested incentives would be better aligned because manufacturers would be “taxed” for high-cost drugs.

Such a proposal would clearly benefit insurers because it would subject manufacturers to unlimited liability, particularly for higher cost drugs. It gained political currency when the center-right American Action Forum (AAF) group endorsed the proposal and came to be referred to as the “AAF proposal” by Hill staff.

Finance Bill’s Disproportionate Impact on Products for Complex Conditions

The bill was introduced and voted on by the finance committee in a span of two days. The drug industry found itself scrambling and somewhat divided over the redesign features since manufacturers of modestly priced drugs saw their liabilities drop while manufacturers of expensive, specialty products saw their liabilities skyrocket.

In October, Avalere Health produced analysis showing that manufacturer discounts on certain drug classes would increase exponentially under the finance committee’s approach. It estimated the following increases for each class of drug:

- Antivirals: 725 percent

- Antineoplastics and adjunctive therapies: 469 percent

- MS and antidementia agents: 293 percent

- Anti-inflammatory analgesics 742 percent

This radical change to the benefit would clearly apply a very punitive innovation tax on products to treat the most complex diseases and amounted to an industrial policy of choosing winners and losers. The industry has since united on a position that any required manufacturer discount should be uniform and reinvested into benefit improvements.

House Alternatives Emerge

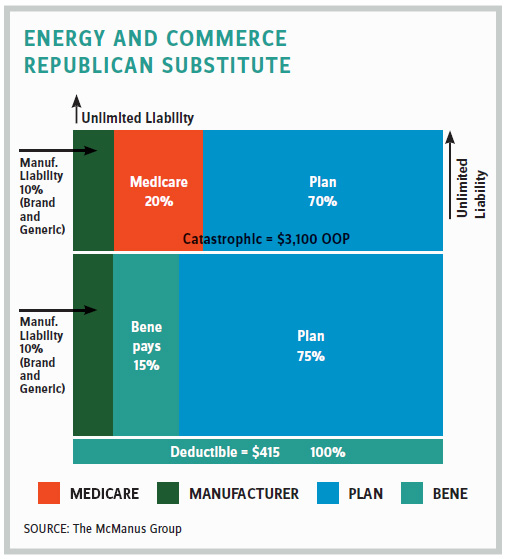

The Speaker’s bill one-upped the finance committee’s bill by applying a 10 percent manufacturer discount in the initial benefit and a 30 percent discount (i.e., 50 percent higher than finance’s 20 percent) in the catastrophic benefit. These manufacturer discounts would apply to drugs other than the top 250 most costly drugs subject to the international pricing scheme.

What is next?

While focus remains on the House vote of Speaker Pelosi’s bill, bipartisan staff are still in communications about these Part D redesign components. However, it is possible an end-of-year deal could materialize and potentially include a restructuring of Part D, but it’s more likely negotiations would hold over into Q1 next year.

There are a lot of moving parts on Part D redesign. But one aspect has received far too little attention: Drastically reducing Medicare’s reinsurance from 80 percent to 20 percent, which is inherent in ALL the proposals, could have a dramatic impact on plan participation in the program. Too much risk on the plans may cause many to throw their hands in the air and exit the market. Part D has been successful because it has fostered competition of multiple plans in every region that is vying for beneficiaries’ business and must compete by keeping costs low. No region has fewer than 22 plans.

In contrast, most states have fewer than five Affordable Care Act plans and 21 states two or fewer issuers. That may be fine for many Democrats who want a single-payer system, but for those of us who believe in choice and competition, key features that have made the Part D model successful should not be abandoned.

More deliberation is needed before Congress proceeds.

John McManus is president and founder of The McManus Group, a consulting firm specializing in strategic policy and political counsel and advocacy for healthcare clients with issues before Congress and the administration. Prior to founding his firm, McManus served Chairman Bill Thomas as the staff director of the Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, where he led the policy development, negotiations, and drafting of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. Before working for Chairman Thomas, McManus worked for Eli Lilly & Company as a senior associate and for the Maryland House of Delegates as a research analyst. He earned his Master of Public Policy from Duke University and Bachelor of Arts from Washington and Lee University.