The Secrets To CSL Limited's Incredible Revenue Growth

By Rob Wright, Chief Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @RfwrightLSL

Like any pharma CEO today, Paul Perreault talks a lot about the importance of the “voice of the patient” in drug development. Patient-centricity is, after all, a prerequisite industry buzzword these days. But when Perreault talks about this topic, it doesn’t have the usual hollow ring of marketing fluff; he cites examples and specifics that add credibility to this “strategy.”

But part of that credibility comes from the man himself. Since taking over as CEO and managing director of CSL Limited in 2012, the 36-year industry veteran has helped the company increase revenue by 33 percent. Did he slash R&D or perhaps hold off on making capital improvements just to make the numbers? Not according to CSL’s most recent financial reports. Instead, the company has increased R&D by 73 percent and capital investment by 83 percent. Perreault admits there are multiple drivers to this level of success, but it all starts with a focus on patient education.

START EDUCATING EARLY, AND TOUT THE DATA

“Within the United States we have developed close collaborations with all of the relevant patient disease organizations, as well as those more broad-reaching groups [e.g., the National Organization for Rare Disorders],” Perreault says. Those efforts are intended to help educate patients and providers toward better diagnoses. In addition, the company educates Washington insiders on the need to make sure orphan and rare diseases legislation is in alignment with commercial efforts.

“Before Phase 3 of clinical trials, we also like to talk to insurance companies because, by then, we have a good idea of what the therapeutic will cost, so we want to make sure patients are going to have access,” he explains. “If you don’t start that conversation early, you can go through a heck of a lot of development and get products approved that nobody is willing to pay for.” He says he’s seen it happen in both Europe and the U.S. And it’s not just having those conversations early; its providing data on how a new therapeutic is going to impact the lives of patients and lower the long-term costs of care.

For example, in December 2016, The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, a specialty journal, published findings of the CSL-sponsored RAPID Open Label Extension study. Conducted in patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD), the study data demonstrated that the use of Alpha-1-Proteinase-Inhibitor (A1-PI) therapy slowed the progressive and irreversible loss of lung tissue. “Alpha-1 is one of those diseases where it looks a lot like COPD, so the awareness and diagnosis is tough,” Perreault contends. “I’ve spoken to pulmonologists who have said they have never seen an alpha-1 patient. When I ask if they’ve ever tested for it, they usually say no.”

He says in the alpha-1 space both physicians and payers needed a lot of education. But having the data from this study, which demonstrates disease modification, certainly helped the discussion. “When designing clinical trials today, you need to make sure the data you collect supports your pharmacoeconomic proposition,” he says.

GLOBAL AND INTERNATIONAL ARE NOT THE SAME THING

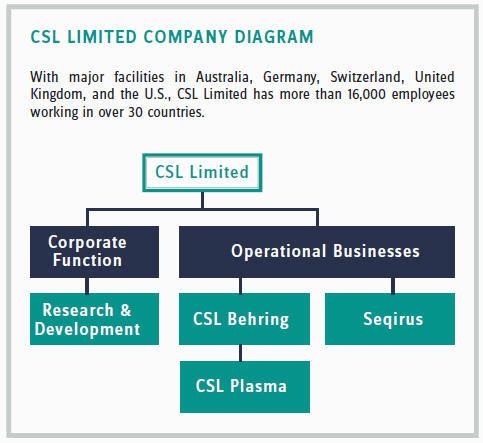

Although focusing on education for patients, payers, and legislators is a key part of CSL’s business strategy, the enormity of that task isn’t immediately evident until you consider that this is a global company conducting business in more than 60 countries, yet is headquartered in Australia. “We are one of the few companies that have successfully globalized out of Australia, because Australia is a long way away from anywhere,” Perreault quips. “The difference between us and a lot of Big Pharma companies is that they talk about being global, but are actually international, operating independently in all of the countries in which they do business.”

To further explain how this global moniker impacts the company’s business, he says decisions aren’t made based on one market without first checking with all the other markets. It’s more of a long-term view, meaning, for instance, that the company wouldn’t abandon a market simply because product sales are struggling. Similarly, the promise of a high price for a product shouldn’t be the sole reason to enter a market. “Neither customers nor patients like such approaches since each represents a lack of commitment to a medical community,” Perreault explains. “If you’re going to enter a market, you need to know that you have a sustainable platform and strategy, and you don’t leave when you have a problem or need a better price to raise profits.”

Outside of the United States, which represents the bulk of CSL’s business and a key growth area, the company has operations in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Europe, and Mexico, just to name a few. “All of these have been good growth platforms for us, built on the back of initiatives we have for awareness and diagnosis of various rare diseases,” he says. “Areas like Latin America and some of the other countries I mentioned are really starting to come into their own as a result of the patient advocacy and education we have supported.”

Japan, though, required some customized attention when it came to developing those education initiatives. “Japan is a really tough place to do business,” Perreault admits. In particular, the company wanted to educate the older Japanese medical professionals about primary immunodeficiency, a group of more than 300 rare, chronic disorders in which part of the body’s immune system is missing or functions improperly. To do so, CSL helped establish the Primary Immunodeficiency Database in Japan (PIDJ). “We found some younger Japanese immunologists who were more on the cutting edge of what’s happening in immunodeficiency,” he explains. “Now, with the PIDJ, it has become a reference center of excellence, enabling younger and older immunologists to share new information and best practices.”

GROWTH BY ADDING ONTO A CORE BUSINESS

Beyond its global education initiatives, CSL achieved growth in recent years a more direct way — through acquisitions. On this topic, Perreault is also effusive, lobbying for a more thoughtful approach. “I frequently say, don’t get entertained by stuff you don’t understand,” Perreault counsels. “For example, say a company is facing a big patent cliff. So, looking for future growth, they decide to buy another company’s product. But two or three years later, they want to jettison it because it’s no longer ‘core’ to what they do. Often, the end result is a lot of wasted time and effort.”

So why did CSL — a specialty biotherapeutics company that primarily develops biotherapies from human blood plasma — decide to buy the Novartis flu business for $275 million in 2014? To answer that question, you first need to understand the flu business.

Unlike most vaccines, which are developed and pretty much stay the same for 50 years, when you develop flu vaccines you develop and register a new product about every six months. You’ve got one flu vaccine for the Southern Hemisphere and another one for the Northern Hemisphere; different strains require flu companies to do safety trials in both hemispheres every year. “In other words, getting into the flu business is not for the faint of heart, and to be successful requires you to be highly focused on the flu business,” explains Perreault.

He contends that CSL’s acquisition of the Novartis flu business was a good strategic decision because they were the only manufacturer in the Southern Hemisphere, of any scale whatsoever, in influenza. “We have pandemic contracts with the Australian government, and that flu infrastructure also supports some of our antivenoms and antitoxins [medicines of national importance for Australia] work.” According to Perreault, when people in Australia get bit by snakes or spiders or are stung by jellyfish or other sorts of creatures, it is CSL that makes all of the remedies. Purchasing the Novartis flu business gave CSL the necessary scale to go global with its existing flu business.

Besides scale it was also a good deal. “They had great cell culture assets in Holly Springs, NC, a facility that cost over $1 billion to build,” he relates. “Novartis also had a facility in Liverpool that’s a former Chiron plant that they had put a lot of money into.” In early 2016, the company announced the combination of the former Novartis flu business with CSL’s existing vaccine business would operate under the brand Seqirus, making the company the second-largest influenza vaccine provider in the $4-billion global market. While not yet profitable, Perreault anticipates getting to break-even by 2018. “The goal is to be profitable by 2020, having about 20 percent EBIT margins, and around $1 billion in sales,” he says. In the meantime, the focus is on ramping up flu doses. “The first season we got out 8 million,” he concludes. “We need to get to 25 million, then 30 million, and eventually 60 million flu doses to really achieve scale.”

While Perreault acknowledges CSL’s future success begins with a focus on patient education, it ends with looking beyond plasma. “Having launched two new recombinants this past year, we certainly have capabilities in this area,” he reiterates. “But we’ve added competencies in others as well.” For example, back in 2006, the company acquired an Australian antibody company (Zenyth Therapeutics) for $104 million. And while this added a lot of antibody assets to the company’s portfolio, it also brought a lot of knowledge on which CSL can build. “We’re not looking for bolt-ons that provide a one-year positive raise to revenues. We are looking for things around our core capabilities, competencies, or adjacencies that we can add value to and can grow over time, and this requires disciplined decision making,” he concludes.

EDUCATING PAYERS WITH PATIENT ADVOCATES

“We know that not every patient is going to be a perfect fit for our products,” says Paul Perreault, CEO and managing director of CSL Limited. “Sometimes patients have reactions after being switched to a new drug.”

And while having a 100 percent market share would be great, he is not interested in the use of closed insurance formularies to achieve such an end. “We want to make sure that formularies have multiple options,” he states. “In the rare disease communities, patients need choice.” To help achieve this, CSL has patients advocate on the company’s behalf. “We’ve brought patient advocates to speak to payers on the importance of choice,” Perreault shares. “Not only does this help educate the payers, it provides patients an opportunity to have a loud voice at a high level within the payer community.”

Perreault and his team are also trying to encourage payers to think more long term, which is hard. “They’re trying to save money today, so it’s not easy to pull costs out of the system.” He says CSL talks with payers about their business model and seeks to understand what they are trying to accomplish as an organization. “Drug companies have to look beyond drugs when working with insurance providers,” he explains. “We need to ask what’s happening in terms of care, tests, and utilizations. We also need to know what we can add regarding how to diagnose certain diseases.” In doing so, CSL hopes to help prevent people from wandering through a healthcare system for many years trying to get diagnosed. “We need to understand their model of delivery if we want to help them better deliver care for patients with rare diseases,” he concludes.

CSL CEO STRESSES NEED FOR “GENERAL MANAGEMENT”

CSL CEO and managing director Paul Perreault says he never set out to be the CEO of anything and certainly never aspired to head an Australian biopharmaceutical company. “I am surprised as anybody to be in charge of this company.” He says his rise to the top position at CSL happened through teachable moments, as well as unexpected opportunities.

Shortly after graduating college, Perreault began his biopharmaceutical career as a field sales representative with A.H. Robins. “I learned early in my career the importance of taking on additional responsibilities,” he shares. While still a rep, his boss told him there was an opening for a regional trainer and asked if Perreault wanted to apply. But he was reluctant, primarily because he didn’t want to leave his customers. His manager assured him that he’d continue to have a sales territory, though it’d have to be shrunk to accommodate his training responsibilities. “The one thing I learned from my regional trainer experience is that not everybody worked or was motivated the same way I was,” he admits. This lesson was even more evident when he took his next job as district manager.

“I took over a district that was 45 out of 45 in the country,” he recalls. “I started my first meeting with motivational posters on the walls — which all went over like a lead balloon.” Perreault shares that he failed miserably in his first year as a manager. “I was clueless when it came to people,” he admits. “Understanding the importance of having the right people motivated around the right things was a key teachable moment for me as a young district manager. After a year I realized I had to get the right people working in the company to do the job that needed to get done.” Over the next two and a half years he ended up turning over about 10 out of the 12 sales representatives, and the team moved from worst to first.

Other teachable moments occurred as he continued throughout his career. “Today, everybody wants to be a specialist,” he asserts. “General management seems to be a declining skill, yet one greatly needed in today’s environment.” For example, Perreault has experience in operations, sales, marketing, training, management, and finance. “When it comes to leadership, I think the broader your experience, the better,” he explains. “If you don’t have enough breadth to understand the big picture of a business, how are you going to be able to ask the right questions or see the interplay and intricacies critical to making it successful?” But don’t only aspire to take on different roles in an organization. “The more diversely you read, the better your thinking will become,” he says. “Teachable moments are all about the learning, not the lesson.”