The 5-Step Strategy That Saved Genmab From A Dire Outlook

By Rob Wright, Chief Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @RfwrightLSL

With six consecutive years of profitability (ahem, soon to be seven) and a market cap of nearly $13 billion, Genmab A/S represents one of Europe’s brightest biotech triumphs. But such wasn’t always the case.

Jan G. J. van de Winkel, Ph.D., cofounder, president, and CEO since 2010, remembers when Genmab faced some pretty tough decisions. How tough? How about completely writing off a $240 million manufacturing facility acquired just two years previously. Try renegotiating an agreement with a Big Pharma, knowing that if they don’t play ball your company could be staring at a dire financial outlook. Imagine cutting hundreds of jobs when blockbuster success seems right around the corner. Many will likely be surprised to learn how close Genmab came to walking through death’s door. And while some believe that facing such adversity builds character, for Genmab and van de Winkel, it revealed it.

Why Buying A Manufacturing Plant Turned Out To Be A Terrible Decision

Van de Winkel served as CSO since Genmab’s inception in 1999 and worked as the head of research and preclinical development through April 2008, which is when he became president of R&D and CSO. Just two months prior, Genmab had agreed to purchase PDL BioPharma’s 22,000-liter antibody manufacturing facility in Brooklyn Park, MN, for $240 million. This decision was based on the robust growth of programs Genmab had moving toward the clinic in 2007. And though just settling into the new position, van de Winkel could already see Genmab needed to refocus. “We had too many programs being made ready for the clinics when the financial crisis hit.” And though the company had been producing some small batches that could be used in development work, by that summer (2008) he knew the facility needed to go. But van de Winkel says liquidating a facility in the same year acquired was too difficult a decision for the board of directors at the time. “It wasn’t until late 2009 that the company finally decided to bite the bullet,” he states.

Genmab was experiencing little financial strength, a rapidly rising expense base (i.e., 170 employees in Minnesota alone), a global financial crisis, and, on top of that, an increasingly challenging relationship with a key strategic partner. “GSK had made up its mind to move out of oncology, which was too bad because Arzerra (ofatumumab) [the drug the companies had been codeveloping] was an oncology product,” he asserts. “What we really needed to do was to make the company somewhat independent of the stock market by focusing on what we’re really good at.” That involved discovering new antibody therapeutic molecules, and then entering into new partnerships so companies could access Genmab products, technologies, or capabilities. “We needed a royalty model that would create an alternative income stream to keep the company afloat until we would become sustainably profitable,” he states.

In late 2009, Genmab announced a reorganization plan in hopes of saving $60 million. The structure involved a layoff of 300 employees along with the planned shutdown and sale of its plant in Minnesota. But there was just one problem. Because this was the peak of the Great Recession, not many companies were buying $100 million manufacturing facilities. In other words, the company needed a new strategy and leader in order to change Genmab’s fortunes.

Step 1

Renegotiate For Win-Win Collaborations

By June 2010, the company had experienced an over 80 percent decline in its stock value (over a three-year period), and it was announced that Genmab cofounder and CEO Lisa Drakeman, Ph.D., was retiring from her leadership and board of director positions. In her place stepped in van de Winkel. Realizing the significance of the company’s plight, he knew the company needed a new strategy to get things righted — and quickly. But he was adamant that whatever strategy he devised would not give away the creative heart of the company (i.e., expertise in antibody biology and antibody innovation). “Most companies going into a restructuring while under duress might aim to protect the lead clinical program closest to the market and stop or liquidate all earlier developments, but we actually protected our research and preclinical engine during this phase,” he states. Here’s what van de Winkel did as incoming CEO:

First, he renegotiated the agreements Genmab had in place with GSK for Arzerra. According to van de Winkel, the Arzerra program had expanded beyond the oncology focus originally envisioned in 2006. The idea of the original contract was for Genmab to be getting milestone payments from GSK, which it would use to fund its 50 percent share of development costs. However, there was considerable dispute over some rather big milestones, and Genmab was not receiving payments van de Winkel believed the company was entitled to. “We were squeezed into a corner,” the executive admits.

Within a day of being named Genmab CEO, van de Winkel made a very important phone call. “I contacted Moncef Slaoui, Ph.D., then head of R&D for GSK, and said we both have an issue,” he recalls. Van de Winkel explained that without a renegotiation of their contracted collaboration, Genmab would be forced to go out of business and proposed getting together to hash things out — quickly. “We needed the negotiation to take two or three days, not three or four months,” he emphasized. Van de Winkel, along with a few colleagues and a GSK team headed by Slaoui, started on a Wednesday. “By Friday afternoon of that same week, we were popping champagne to celebrate the renegotiated relationship,” van de Winkel attests. By the following week, Genmab was able to announce having received a payment from GSK of roughly $135 million, which helped financially stabilize the company. But the agreement also restructured Genmab’s future funding commitment for the development of ofatumumab in oncology indications, which were capped at $25 million annually for the next six years, and not to exceed $220 million in total. “I wanted to maximize the investment from Genmab into Arzerra per year and in total for oncology, so we were willing to give back some of the rights for autoimmune indications, reduce royalties from 20 to 10 percent, and give up some milestone payments related to autoimmune development,” he explains. Van de Winkel asserts that having a straightforward and strong relationship enabled the two companies to negotiate very quickly.

Step 2

Getting Rid Of Silos

The next thing van de Winkel wanted to get rid of was Genmab’s siloed structure. “Research was hardly communicating with clinical development, and neither was communicating effectively with BD.” To resolve this, he set up “portfolio boards,” which he says the company still uses. Composed of all essential areas of the company, these cross-functional teams meet once a month for intensive discussion involving all parts of the business, not just R&D. “At these meetings we talk about everything from which disease targets to select to which programs we should move to in vivo, into the clinic, or from Phase 1, Phase 2, and so on. There’s more diverse input, which, ultimately, gives us better control over the entire development process,” he asserts. But whatever happened to that $240 million manufacturing plant in Minnesota?

Step 3

Sell The Plant And Adopt A Fully Outsourced Model

Though Genmab had announced plans to close and sell the plant back in 2009, van de Winkel says the process was tough, as there were a lot of other companies looking to sell their manufacturing facilities, too. And though there were plans to write off the 36-acre facility in phases, before the end of 2012 van de Winkel made a very bullish decision. “I decided to completely write off the facility to send a blunt signal that Genmab was getting rid of this plant — no matter what,” he says. And while the executive fully anticipated Genmab’s stock to trade down the very next day, because, after all, writing off $240 million is a pretty harsh thing to do, van de Winkel took delight in being wrong. The stock actually traded up several percentage points, indicating that the market was finally “getting it.”

In February 2013, the company finally found a buyer in Baxter, which paid $10 million in cash and offered employment to 23 employees supporting the facility. “We learned a very hard lesson, and as long as I’m the leader of Genmab I can assure you we will never buy another manufacturing facility,” he states. Rather, Genmab moved to a fully outsourced model for execution of manufacturing and clinical trials. “When we enter into preferred relationships, we tend to interact with these partners as if they are our own colleagues,” he attests. Genmab seeks partners that are flexible, because as we all know, sometimes you encounter hiccups during drug development. And when such hiccups happen, van de Winkel says they try to do whatever they can to keep their partners busy, such as switching from one program to another with the same CMO just to keep their fermenters filled with Genmab antibodies. Though moving to a completely outsourced model can create angst, van de Winkel says seeing pharma powerhouse partners predominantly use CMOs gave him the confidence to proceed.

Though the brokering of strategic partnerships with CMOs and CROs often involves business development teams, van de Winkel says to have meaningful strategic relationships requires engagement at all levels. “You need to be investing in the relationship just as you do with friends and family,” he affirms. And though Genmab has successfully developed relationships with 16 strategic partners, the executive admits it hasn’t been without challenges.

Van de Winkel also has some thoughts when it comes to partnering with other biopharmaceutical companies. “I believe in 50/50s, as there is more at stake for both partners, and both will work much harder to make it a success as compared to when one side has a small stake in the upside of a molecule,” he contends. Van de Winkel references a successful partnership with BioNTech, which has a 50/50 model. Additionally, he points to strategic alliances with companies such as Immatics, and a three-way collaboration between Genmab, Seattle Genetics, and the Netherlands Cancer Institute (NKI). “Enapotamab Vedotin (HuMax-AXL-ADC) is a Genmab antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) armed with a Seattle Genetics warhead (ADC) and, with the help of a group of scientists from NKI, created some amazing preclinical data recently published in Nature Medicine."

Step 4

Develop A New Strategy And A Long-Term Vision

The CEO says he decided to develop a new strategy for Genmab upon first taking the role in June 2010, but wasn’t able to formally introduce it until that September. From 2011 to 2012, van de Winkel, along with Genmab’s then seven-member global leadership team (GLT) and a number of employees from the company’s core sites (i.e., Copenhagen, Princeton, and Utrecht), set out to articulate the company’s vision for the year 2025. “We aspired to transform cancer treatment through the development of a knock-your-socks-off pipeline of antibodies, and we needed colleagues from core sites to help carry this message broadly throughout the company,” he shares. This would require some big-picture thinking. And while the CEO admits that many of the planning meetings began with him delivering long monologues for how he envisioned the future of the company, he incorporated other inspirational tools. For example, he used video clips of President John F. Kennedy’s speeches outlining the country’s aspirations to go to the moon, and he used Henry Ford’s vision of creating an automobile for everyone. He also provided reading materials that included a number of hand-picked articles from Harvard Business Review. “We needed to be bold and through intense discussions came up with a vision statement that still guides us today,” he shares.

Other tactics toward changing the company’s direction involved reengaging employees in rolling out the company’s new vision and strategy focused on its core competencies and building a profitable and successful biotech. Through employee off-sites, including a biennial meeting, all Genmab employees are brought together in one location to discuss the company’s 2025 vision and assess what still remains necessary to reach it.

Step 5

Get R&D Out Of The Basement

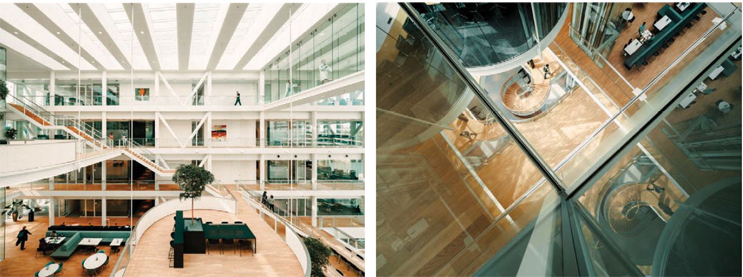

In the original Genmab R&D building in the Utrecht Science Park (USP) in the Netherlands, van de Winkel’s office was located on the ninth floor. “I don’t know who dreamed up that I needed to be on the top floor,” he relates. But such a structure put a lot of distance between him and Genmab employees. So, when the company determined it was time for a new building in Utrecht, van de Winkel definitely had some thoughts about what he wanted to do differently, such as getting R&D out of the basement — and getting his office off the top floor. “I wanted connection, lots of open space, lots of glass, transparent walls, and my office to be at the center of the action.” They also wanted the building to be as flat as possible, as they believed “towers” were not very facilitative to doing innovative work. “We wanted lots of staircases to encourage less use of elevators, as it’s not only healthier, but provides for spontaneous interactions between employees that can lead to good ideas,” van de Winkel elaborates. They also wanted an incredible coffee bar, and here’s why.

Upon entering Genmab’s newly constructed R&D Center in Utrecht (officially opened in June 2018), you’ll run straight into the company’s science café. “The coffee is one fourth the price of Starbucks and ten times better in quality,” the CEO boasts. This was deliberate, as he hoped this would encourage surgeons, postdocs, and researchers from nearby hospitals and institutes to get their morning croissant/coffee at Genmab, and, while there, end up mingling with Genmab scientists. “We’ve created an atmosphere that encourages unexpected encounters and interactions, which not only makes the science café an area ripe for ideas, but creates an energy that makes Genmab an exciting place to work.”

Throughout the new building, there is a lot of glass, which is intended to communicate transparency. There are tables everywhere so people can sit and interact in flexible workspaces, along with 20 or so “concentration” offices that operate on a first-come first-served basis. “We even dreamed up a boardroom that’s circular and hangs in the air centrally in the building,” the CEO adds. And though outfitted with transparent walls, there are curtains, which for the most part remain open, but can be drawn if a meeting requires more discretion. At the center of the boardroom is a triangular-shaped table, and van de Winkel notes this being different from nearly every other boardroom table he has ever seen. “In a normal boardroom, you tend to interact with those immediately next to or across from you, but the triangular shape enables comfortable interactions between 14 or 15 people,” he asserts. “Another thing we dreamed up was a connection in the air between labs in two wings of the R&D building, and you can literally walk through a beautiful atrium from one lab environment into the other.” Van de Winkel believes you’ll never see labs doing important work so transparently at the heart of a biopharmaceutical company’s building. And unlike the days when labs were underground and hidden from view, Genmab’s labs in Utrecht are in the best spaces and get the most daylight; it’s a subtle nod to how important R&D is at the company.

As for van de Winkel’s new office, it too is close to where scientists are mingling on a daily basis. Because after all, as a scientist with more than 300 scientific publications to his credit, he thrives on being near the heart of the action. But this executive isn’t waiting for Genmab employees to come seek him. About every other week or so van de Winkel hosts private lunch meetings with about a half dozen new and veteran employees. “We want a mix of experience and have intense discussions, though everything we talk about is to stay in that room,” he emphasizes.

Though seemingly very pleased with the new facility in Utrecht, the CEO admits there is a negative. “One year after opening it is already full, and so, in the next few years, we are already looking to build another building next door that can be connected.” he smiles.

Genmab’s Path Forward

Genmab has certainly come a long way from where it was when van de Winkel took over as CEO, and just this past year it raised $582 million from its U.S. NASDAQ IPO to further its pipeline of differentiated antibody therapeutics. In addition, the company looks to have seven proprietary clinical programs (defined as 50 percent or more ownership) moving toward the finish line, along with a double blockbuster in DARZALEX, the first approved mAb for multiple myeloma, developed in partnership with Janssen. Arzerra, now with Novartis, holds the potential of becoming a blockbuster through the ofatumumab program in relapse-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). Finally, van de Winkel anticipates Genmab having a third product (now in the hands of Horizon Pharma) making an impact in early 2020. “Teprotumumab was originally created for Roche for cancer, but it didn’t work,” the CEO admits. “So, Roche licensed to a VC, River Vision, which did a trial in Graves’ eye disease and produced strong data.” Horizon filed the biologics license application (BLA) this past July, and received an FDA priority review in September. If approved, Genmab has another royalty stream. “Sometimes it is impossible to predict 15 years beforehand where a drug or medicine will work optimally,” van de Winkel reminds. The same could be said for trying to predict which biopharmaceutical startups will make it for the long haul. And while Genmab and van de Winkel deserve a lot of credit for developing and executing a strategy that delivered Genmab from death’s door, let’s not forget the important role played by the company’s strategic partners. “Being willing to share and work together with partners is very much in Genmab’s DNA, and I believe the drug development winners of the future will be those companies that are exceptionally networked and willing to share knowledge more openly,” he concludes.