What Can Be Done To Save Biopharma's Reputation?

By Rob Wright, Chief Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @RfwrightLSL

“We behave like ostriches. We don’t set the trends but wait for others to set them for us.”

These are the words of Spiro Rombotis, one of the executives brought together to discuss a glaring problem — the negative perception held by the U.S. public of the biopharmaceutical industry.

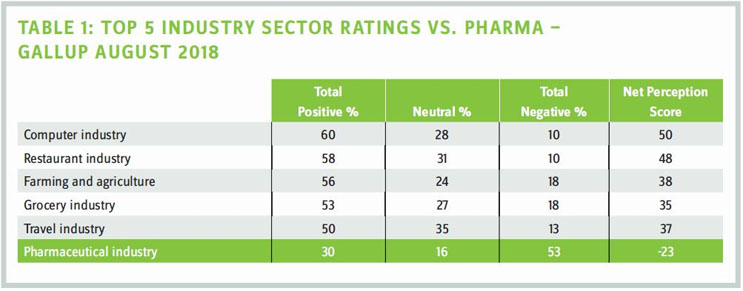

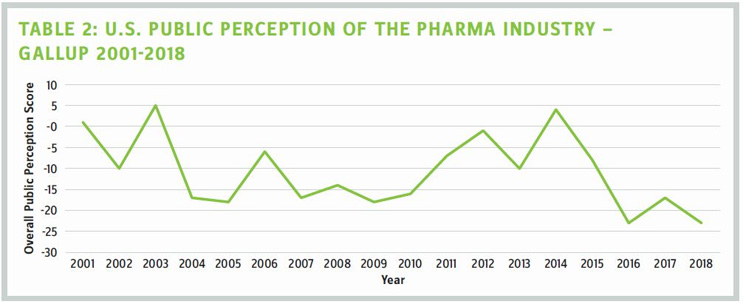

It's noon on Jan. 7, 2019, and with me are four biopharmaceutical executives. We've gathered at the Mystic Hotel, away from the JPM Conference in San Francisco, to discuss what can be done to fix biopharma's broken and battered image. How broken and how battered? Last August, Gallup conducted a poll of 25 U.S. business sectors asking Americans to give their overall view of each. Of the 25 industries, pharmaceuticals achieved a score of -23 (second from the bottom). Now before you say, "That's probably an anomaly," you should know that Gallup has been conducting this poll since 2001. And in the last 17 years, our industry has been perceived positively. Barely. On only three occasions (see Table 2).

During the roundtable we focused on two basic questions:

- How did biopharma's reputation get to where it is?

- What can we do to fix the problem?

The biopharmas from which the participants hail are all on the smaller side (i.e., privately held or publicly traded with market caps ranging from $10 million to $228 million). This was done purposefully, as we hoped to gain perspectives that were not the well-polished talking points of Big Pharma or heads of industry trade associations (i.e., BIO and PhRMA).

The primary goal of our discussion was to come away with some actionable information you could begin using tomorrow toward fixing our industry's negative image. So, after some brief introductions and exchanging of business cards, we got down to business.

WHAT CAUSED BIOPHARMA’S REPUTATION TO BE WHERE IT IS TODAY?

Spiro Rombotis kicks off the conversation with his thoughts on members of biopharma burying their heads in the sand while waiting for others to set the trends. He elaborates, noting that those who do set the trends (e.g., politicians) typically have little understanding around the dynamics and difficulties associated with financing biopharma innovation. “In the U.S., we have a market-based, resource-allocation mechanism that has been tested for over 40 years, and if we do something to change that (i.e., price controls), we do so at our own peril,” he states. “We need to be the ones educating politicians, rather than letting them come up with solutions and us trying to do damage control on misguided solutions that won’t be able to be fixed in our generation.”

The discussion continues with James Dentzer sharing the opinion that today’s biopharma leaders tend to be R&D-heavy in background and inwardly focused on their individual companies’ science, while those outside the industry tend to focus on the costs they can see — marketing and advertising. “The impact of these externally visible costs on a macro level is often an afterthought among today’s industry leaders, but that is changing,” he shares. “The bigger issue, that I do not see changing, is the issue of where we as a society choose to spend our money. We are creating billionaires among tech and internet companies, because we simply can’t live without the next iWatch. There is no Gates or Zuckerberg in biotech because we choose to spend our money on gadgets, not healthcare.” Dentzer feels that as a society we have our priorities a bit out of whack.

Realizing we are not addressing the reputation question, Sutro’s Stephen Worsley begins, “During Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 presidential campaign, Democratic strategist James Carville coined the phrase, “It’s the economy, stupid.” Translated to our industry, “It’s all about costing.” According to Worsley, there have been too many occasions when a new drug is debuted at a certain price, and everybody screams. “We need to be paying more attention to the pharmacoeconomics earlier, play a stronger role in how drugs get administered, and do some self-policing with how new technologies (i. e., CRISPR) are being utilized, or government is going to do it for us.”

For Gil Van Bokkelen, Ph.D., several issues come to mind, beginning with bad actors that are the last ones standing in a generic space that now has and applies pricing power. “That’s reflective of a dysfunction in the existing system for generics, which provides cost savings and delivers substantial value in many instances, but not in situations where you drive out all competitors and eventually have only a single entity remaining that then raises prices, or when everybody exits a drug entirely, because the intense competition has made it unprofitable,” he says. Major biopharmas adopting a mind-set of annual price increases, warranted or not, are another contributor. “Leaders need to recognize that it can’t be all about price maximization, and we need to do a much better job of conveying a medicine’s value to the entire healthcare ecosystem,” Van Bokkelen shares. “For example, there’s no question Sovaldi is transformative and is helping many patients and is also saving the healthcare system a substantial amount of money over the long term. But when launched with a big price tag, they failed to effectively explain ahead of time why it was so valuable, and that resulted in a backlash. It was a missed opportunity and a huge tactical mistake we should all learn from.” In addition, he believes biopharma needs to take a leadership role in figuring out better reimbursement and payment models.

Our virtual participants chime in:

“Egregious examples of price gouging by biopharmas, combined with stories of people choosing between food and paying for their medications, has resulted in a mischaracterization of our industry operating out of greed rather than doing good,” shares Wendye Robbins, M. D. “Our industry must figure out how to overcome this mischaracterization and communicate directly to stakeholders, including patients, about what we are doing and why.”

Brandi Simpson notes a myriad of issues contributing to the public’s disdain for biopharma. “Pricing and the perception that our companies are unethical are big contributors to the low opinion of our industry,” she shares. Simpson notes that Americans know they are paying far more for pharmaceuticals than patients in other countries, resulting in a perception that industry overcharges U.S. patients to make up for other countries’ price controls. “When companies receive multimillion or billion-dollar fines for unethical or illegal behavior, why wouldn’t someone conclude that the industry is prioritizing profits over human safety and ethics?” she adds.

William Newell notes high-profile political campaigns focused on pricing practices, along with high co-pays and rising co-insurance costs that have limited access to important therapeutics for many, have hurt the industry in the court of public opinion. “A perceived onslaught of “me-too” products and extensive DTC ads undercut our reputation for delivering innovative and breakthrough therapeutics for serious diseases,” he contends.

IS DTC ADVERTISING GOOD FOR BIOPHARMA’S REPUTATION?

Unprompted, the roundtable conversation eventually winds itself to the topic of DTC advertising, with Rombotis asking, “Why is DTC a good thing for our industry?” The question sparks discussion, and a story is shared of a physician noting how a TV commercial for a particular ailment resulted in a large number of patients seeking treatment. Prior, these patients weren’t aware that their condition had a viable solution. “I don’t think we fully understand the consequences of what DTC has done,” Rombotis shares. “Today when there is a TV commercial break, it feels like a lot of ads feature someone walking in the woods sharing why they now feel better about their terminal disease.” His concern is that DTC provides a short-term benefit for one particular owner of a drug, while hurting the reputation of the entire industry.

Dentzer adds that the amount of money spent on DTC could easily be put to better use in R&D or in support of more modest price increases. But he also notes that DTC has become an important revenue stream for networks. As such, any law geared toward eliminating DTC in the U.S. would be fought “tooth and nail” by outlets now dependent on biopharma advertising dollars. “DTC is a solution for a problem that no longer exists,” he states. “In the pre-internet era, it was important. That’s how many patients learned about new treatments. But today, a patient diagnosed with cancer goes straight to the internet and very quickly becomes an expert oncologist.” Dentzer favors an open environment rather than a regulation preventing DTC in the U.S. But Rombotis fears biopharma DTC sends the wrong message. “The saturation level of DTC advertising tells the average person that the drug industry has money to spare,” he states. “It’s not about the substance or even the compliance of biopharma with DTC, it’s the optics.” He goes on to note the fanfare with which Steve Jobs would launch new products or share big ideas when serving as Apple’s CEO. Tech has the likes of Bill Gates, retail Jeff Bezos, and finance/investing Warren Buffet. “Because we [biopharma] are a leaderless industry [i.e., no face with which the public identifies], we are invisible,” he states. “As the general public doesn’t know who is making decisions, it creates the impression of a bunch of fat cats who only care about padding their pockets.” Rombotis attests to biopharma desiring to be perceived as partners and an integral part of providing the best quality care money can buy, but believes we are failing in that message, because we haven’t taken the time to understand what the public needs or wants. “We know that Jane and John Q. Public are the ones who vote and decide whether we are publicly appealing or not, and we aren’t addressing them at all,” he admonishes.

WHAT CAN BE DONE TO FIX BIOPHARMA’S IMAGE?

During the conversation, some big-picture solutions were discussed [(e.g., how to improve healthcare, how to make health insurance more efficient), which I look forward to expanding upon in an online publication]. And while these were interesting explorations, the reality is these fixes would require decades. As the goal was to come up with solutions to the industry’s reputation problem that can be implemented today, we begin with input from our virtual participants.

According to Simpson, if we as an industry don’t address pricing, the U.S. government will eventually do so for us. “Industry leaders must cooperate in good faith to agree to basic pricing principles (e.g., lower prices on branded drugs no longer patent-protected, limits on unjustified price increases). Though lower margins will result, the outcome will be far more favorable than waiting until public outcry surpasses our ability to decide our own future. Patent reform should also be part of legislation to get more affordable therapies to patients sooner, while reducing the ability to create patent thickets or otherwise prolong patent life for the sake of keeping generic and biosimilar competition at bay.”

Newell stresses that the industry should acknowledge that many patients feel priced out of their medicines and that business as usual cannot continue. “Different methods of pricing should be embraced. We should seek to pass through to patients — directly — existing price rebates and discounts paid to pharmacy benefit managers. We need reforms capping copays and co-insurance at reasonable payment levels, while still allowing the neediest to receive drug-cost assistance through expanded-access programs. We should focus the discussion on bringing healthcare costs down, not just on reducing drug prices.”

To Robbins, the problem is perception and, to fix it, we need to find ways to tell stories about the companies that have made a huge difference in people’s lives. “But we cannot lose sight of our work, which is curing diseases and saving lives. I am working with the California Life Sciences Association (CLSA) in getting that messaging out, while also being active in my community as a mentor to students, especially those interested in STEM.”

In fixing the industry’s reputation, we seem to have a good idea on the “what” that needs to be done, and Robbins’ comments provide an important transition regarding the “how” to go about doing so. From our live roundtable participants, we gain the following.

“It needs to be a joint effort of applying pressure with government, advocacy groups, payers, and industry specialists to get the message out about what’s happening. PhRMA’s GoBoldly campaign is a good start, but I wonder if it is more fluff than we need,” concludes Worsley.

“My proposed formula is to work at the state and local government level, as that’s where the budgets that matter are, and they understand biopharma’s importance to their tax base. To get the industry’s image to become more social with everybody’s livelihood requires grassroots engagement with people before voting age, so biopharma can become part of their everyday experience, just like sports, cell phones, or anything else somebody wants to engage with. Through BIO NJ, we take young students from STEM programs into internships to give them a sense of what biopharma is about. With state legislators we don’t talk about the innovation of one company’s drug, but the worth of socializing at all layers of society the value of innovation and the importance of having intellectual heroes (e.g., scientists) on Instagram and TV,” shares Rombotis.

Van Bokkelen adds, “As leaders in the industry, we need to be willing to be part of the discussion and debate. This requires devoting time and effort to educating others. But we also have to be willing to listen and take an objective look at things happening in our industry that are having a negative effect and hold each other accountable. Divisive, visceral overreactions so common today impede the ability to have honest conversation about the issues, challenges, and steps to take to improve the system without inhibiting investment and innovation.”

Dentzer concludes the discussion by stating, “Drugs are expensive because the cost of complying with government regulation is so high. That is unlikely to change anytime soon. So, in the short term, the best thing for the industry and for patients — that everyone’s going to hate — is that we need to prepare ourselves for criticism and push for even higher drug prices. Here’s why. Higher-priced therapeutics have made it economically viable to chase after more targets and more diseases, and the amount of innovation and value creation has mushroomed as a result. U.S. investment dollars that would have gone to other industries are being put in biopharma, and society is benefitting. Reducing drug prices, without also reducing the cost of drug development, will siphon off capital, reducing or eliminating the possibility of providing the innovative medicines we all want."

Participants of the live discussion included:

GIL VAN BOKKELEN, PH.D.

chairman and CEO of Athersys Inc.

JAMES DENTZER

president and CEO of Curis

SPIRO ROMBOTIS

president and CEO of Cyclacel Pharmaceuticals

STEPHEN WORSLEY

chief business officer of Sutro Biopharma

In addition, we invited the following three executives to participate virtually:

WENDYE ROBBINS, M.D.

president and CEO of Blade Therapeutics

BRANDI SIMPSON

president and CEO of Navigen

WILLIAM NEWELL

CEO of Sutro Biopharma