Whistleblower Best Practices

By Gail Dutton, Contributing Writer

Follow Me On Twitter @GailLdutton

At some point in the life of a pharmaceutical company, a whistleblower is likely to come forward with allegations of wrongdoing. The intricacies of marketing alone can create a minefield of potential mistakes.

Your best defense begins now.

WHAT THE DOJ LOOKS FOR

“The Department of Justice [DoJ] is focused on ensuring companies constantly monitor operations to determine whether there are compliance problems,” Gejaa Gobena, partner at law firm Hogan Lovells, says. Monitoring is tied to a robust compliance program that includes a multiyear audit program and to a culture that encourages employees to report possible wrongdoing.

Not everything will be captured during an audit, so if a company doesn’t encourage employees to come forward, the DoJ assumes the company turns a blind eye to misconduct,” Gobena says. “If, on the other hand, a company encourages reporting and addresses issues effectively, the DoJ takes a more favorable view of the company and its intentions.”

The main elements the DoJ considers in whistleblower programs are:

- whether the compliance department is adequately funded to do what’s necessary

- how independent the compliance department is from the rest of the business

- how much it is respected by the business side of the organization

- how problems are remediated once they are discovered

It’s important that investigators dig deeply enough to understand the pervasiveness of a problem, whether the company takes the problem seriously, and how it was remediated. Options extend beyond the surface problem to address the deeper issues by retraining, reassigning, or firing staff.

BEST PRACTICES: SOX AND BEYOND

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 stipulates that companies establish whistleblower hotlines. “In 2017, best practices use email, web links, the postal service, and phones,” says Kathleen Marcus, former SEC attorney and shareholder at law firm Stradling in Newport Beach, CA.

“When companies set up web links and hotlines, they often promise they’ll investigate each complaint. I’d advise companies not to promise how they’ll respond, but instead, encourage employees to use the hotline,” Marcus says.

“Companies with a compliance officer should have an open-door policy, too,” she adds. Face-to-face conversations provide a sounding board and help the compliance officer gather enough information to launch an investigation. It also provides a degree of accountability, ensuring the whistleblower knows a specific person is responsible for investigating concerns.

Establishing an open-door policy and whistleblower hotline are only the beginnings, though.

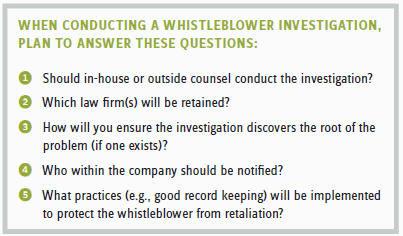

To mount a robust investigation, you need a comprehensive plan that specifies such details as whether in-house or outside counsel should conduct the investigation, which law firm to retain, strategies to ensure the investigation discovers the root of the problem (if one exists), whom to alert within the company, and practices (especially good record keeping) that protect the whistleblower from retaliation.

“The level of formality in structure and process signals the relative degree of seriousness with which complaints are viewed within a company,” says Kent Sullivan, partner at Jackson Walker law firm in Austin, TX, and a participant in the State of Texas’ Medicaid fraud litigation against Johnson & Johnson.

Best-practice whistleblower programs should have written policies and procedures that specify contacts. That includes a compliance officer and boardlevel compliance committee. “Establish effective lines of communication before complaints arise,” Sullivan advises.

“I look for other indicia of a culture that allows for and encourages complaints in general. That’s a starting point for me,” he continues. For a culture to encourage dissent, employees need to know that confidentially will be maintained and that meaningful anti-retaliation policies are not only in place but followed. Corporate training and education programs also should be in place to enhance compliance.

Providing meaningful feedback to whistleblowers also shows companies are serious about resolving complaints. “If you’ve conducted a sufficient investigation and determined the whistleblower allegations have no credibility, communication becomes key,” Marcus says. “If you can identify the whistleblower, it may be important to speak with them about the investigation. Let them know the investigation is completed, the scope of the investigation, and the reasoning behind the conclusion.”

When designing a whistleblower program, also consider the form of the final report. Typically, the report will be presented to a special board committee or possibly the full board. Whether companies have written or oral reports may have consequences later. For example, Gobena says, “If counsel can convey findings orally, that may be advantageous. But, if it’s necessary to document investigative findings, a written report may make sense if it’s written knowing it may be requested by the government later.”

ADAPT YOUR STRATEGY GLOBALLY

Companies operating internationally should develop global whistleblower programs. “With the free flow of people and information across borders, this is one of the great challenges of our time,” Sullivan says.

Your U.S. strategy can lay the foundation, but compliance programs in each nation in which you operate must meet the highest standards (which aren’t always American) and be adjusted for each country. “Ensuring the hotline is in the language of the region is only a starting point,” Marcus says. “Consult with local counsel to ensure that nation’s requirements are met. For example, France discourages anonymity while the U.S. allows it.”

Your U.S. strategy can lay the foundation, but compliance programs in each nation in which you operate must meet the highest standards (which aren’t always American) and be adjusted for each country. “Ensuring the hotline is in the language of the region is only a starting point,” Marcus says. “Consult with local counsel to ensure that nation’s requirements are met. For example, France discourages anonymity while the U.S. allows it.”

RELATIVE MERITS OF IN-HOUSE OR OUTSIDE COUNSEL

“Either in-house or outside counsel may be appropriate, but it’s safer to have outside counsel,” Sullivan continues. “Confidentiality issues, for example, may be handled easier by outside counsel who can wall off any inappropriate flow of information.” Because outside attorneys don’t have reporting relationships within the company and aren’t located there, they can go where the investigations lead without concerning themselves with internal politics.

Outside counsel also confers greater legitimacy on investigations through its perceived objectivity. Bringing fresh eyes may reveal current or potential problems that may not be evident to those involved in the day-to-day business.

In contrast, in-house counsel’s familiarity with the company and its people helps it identify the important elements of investigations quickly.

A hybrid approach, in which in-house counsel hires outside counsel, blends the best of both options. By not conducting the investigation but remaining involved, in-house counsel can guide the investigation so it is more efficient while calming people within the firm. “This provides a very good check for what outside counsel is doing,” Marcus says. “Investigations tend to expand.” Close involvement of in-house counsel may keep investigations focused on actual risks and thus minimize fishing expeditions.

Be aware, though, that if in-house counsel plays an executive or administrative role, communications with it may not be privileged, Sullivan says. “Working with in-house counsel for whistleblower cases may lead to ambiguity over attorney-client privilege.”

Privilege is complicated, and clients often make inaccurate assumptions. The role of in-house counsel is to represent the company — not individual executives, board members, or employees. Discuss the intricacies of attorney-client privilege with your attorney.

WHISTLEBLOWERS REVEAL THE HIDDEN ZEITGEIST

“There’s almost always something to learn from whistleblowers, even when they are wrong,” Marcus says. Whistleblowers often reflect widespread perceptions. If employees feel they can’t talk with their supervisors or that those supervisors ignore their concerns, they may become whistleblowers either internally or by taking their concerns to regulators.

“This is why a whistleblower program is so important,” she says. By making it easier to voice concerns, people are more likely to try to solve problems internally without needlessly involving regulators.